Vatican City State

October 29, 2008

Dear brothers and sisters:

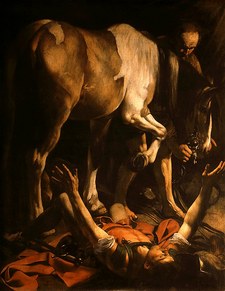

In the personal experience of St. Paul, there is an indisputable fact: While at the beginning he had been a persecutor of the Christians and had used violence against them, from the moment of his conversion on the road to Damascus, he changed to the side of Christ crucified, making him the reason for his life and the motive for his preaching.

His was an existence entirely consumed by souls (cf. 2 Corinthians  serene and protected from snares and difficulties. In the encounter with Jesus, he had understood the central significance of the cross: He had understood that Jesus had died and risen for all and also for [Paul], himself. Both elements were important -- the universality: Jesus had truly died for everyone; and the subjectivity: He had died also for me.

serene and protected from snares and difficulties. In the encounter with Jesus, he had understood the central significance of the cross: He had understood that Jesus had died and risen for all and also for [Paul], himself. Both elements were important -- the universality: Jesus had truly died for everyone; and the subjectivity: He had died also for me.

On the cross, therefore, the gratuitous and merciful love of God had been manifested. Paul experienced this love above all in himself (cf. Galatians

For

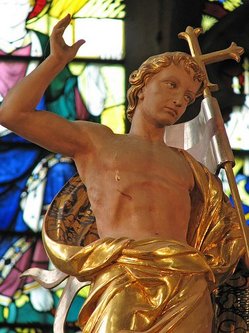

Before a Church where disorders and scandals were present in a worrying way, where communion was threatened by groups and internal divisions that compromised the unity of the Body of Christ, Paul presents himself not with sublime words or wisdom, but with the announcement of Christ, of Christ crucified. His strength is not persuasive language, but rather, paradoxically, the weakness and the tremor of one who trusts only in the "power of God" (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:1-4). The cross, for everything that it represents and also for the theological message it contains, is scandal and foolishness. The Apostle affirms this with impressive strength, which is better to hear with his own words: "The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. ... It was the will of God through the foolishness of the proclamation to save those who have faith. For Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles."

The first Christian communities, whom Paul addressed, knew very well that Jesus is now risen and alive; the Apostle wants to remind not just the Corinthians and the Galatians, but all of us, that the Risen One is always the One who has been crucified. The "scandal" and the "foolishness" of the cross are precisely in the fact that there, where there seems to be only failure, sorrow and defeat, precisely there, is all the power of the limitless love of God, because the cross is the expression of love and love is the true power that is revealed precisely in this apparent weakness.

For the Jews, the cross is "skandalon," that is, a trap or stumbling block: It seems to be an obstacle to the faith of the pious Israelite, who doesn't manage to find anything similar in sacred Scripture. Paul, with no small amount of courage, seems to say here that the stakes are very high: For the Jews, the cross contradicts the very essence of God, who has manifested himself with prodigious signs. Therefore, to accept the cross of Christ means to undergo a profound conversion in the way of relating with God.

If for the Jews the reason to reject the cross is found in revelation, that is, in fidelity to the God of their fathers, for the Greeks, that is, the pagans, the criteria for judgment in opposing the cross is reason. For this latter group, in fact, the cross is blight, foolishness, literally insipience, that is, food lacking salt; therefore, more than an error, it is an insult to good sense.

Paul himself on more than one occasion had the bitter experience of the rejection of the Christian pronouncement judged "insipid," irrelevant, not even worthy of being taken into consideration on the level of rational logic. For those who, like the Greeks, sought perfection in the spirit, in pure thought, it was already unacceptable that God became man, submerging himself in all the limits of space and time. Therefore it was decidedly inconceivable to believe that a God could end up on the cross! And we see how this Greek logic is also the common logic of our time.

The concept of "apátheia," indifference, as absence of passions in God: How could it have understood a God made man and defeated, who later on even had taken up again his body so as to live resurrected? "We should like to hear you on this some other time" (Acts

But, why has

Centuries after Paul, we see that the cross, and not the wisdom that opposes the cross, has triumphed. The Crucified is wisdom, because he manifests in truth who God is, that is, the power of love that goes to the point of the cross to save man. God avails of ways and instruments that to us appear at first glance as only weakness. The Crucified reveals, on one hand, the weakness of man, and on the other, the true power of God, that is, the gratuitousness of love: Precisely this gratuitousness of love is true wisdom.

St. Paul has experienced this even in his flesh, and he gives us testimony of this in various passages of his spiritual journey, which have become essential reference points for every disciple of Jesus: "He said to me, 'My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness'" (2 Corinthians 12:9); and even "God chose the lowly and despised of the world, those who count for nothing, to reduce to nothing those who are something" (1 Corinthians 1:28). The Apostle identifies himself to such a degree with Christ that he also, even in the midst of so many trials, lives in the faith of the Son of God who loved him and gave himself up for his sins and those of everyone (cf. Galatians 1:4; 2:20). This autobiographical detail of the Apostle is paradigmatic for all of us.

St. Paul offered an admirable synthesis of the theology of the cross in the Second Letter to the Corinthians (5:4-21), where everything is contained in two fundamental affirmations: On one hand, Christ, whom God has treated as sin on our behalf (verse 21), has died for us (verse 14); on the other hand, God has reconciled us with himself, not attributing to us our sins (verses 18-20). By this "ministry of reconciliation" all slavery has been purchased (cf. 1 Corinthians

Here it is seen how all of this is relevant for our lives. We also should enter into this

"ministry of reconciliation," which always implies renouncing one's own superiority and choosing the foolishness of love.

"ministry of reconciliation," which always implies renouncing one's own superiority and choosing the foolishness of love.