Georges Rouault was 34 years old and barely recovered from a physical and nervous breakdown when he had a life-changing epiphany in 1905, which he described in a letter to his friend, édouard Schuré. While out walking one day, the artist happened to come across a "nomad caravan, parked by the roadside." It was a circus, preparing for its next public performance. Rouault's eye fell upon one of the figures: an "old clown sitting in a corner of his caravan in the process of mending his sparkling and gaudy costume." It was then that Rouault had a piercing flash of insight, one that was to affect deeply his vision of life and art.

The artist was utterly struck by the jarring contrast between the clown's external garb and

professional accoutrements--"brilliant scintillating objects, made to amuse"--and the wretchedness of his condition as an impoverished, vagabond laborer living on the fringes of society, enduring a "life of infinite sadness, if seen from slightly above." From that contrast came another equally eye-opening realization: "I saw quite clearly that the 'Clown' was me, was us, nearly all of us.... This rich and glittering costume, it is given to us by life itself, we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume...." (Rouault summed up this vision in several studies entitled "Sunt Lacrymae Rerum"--"There are tears [of grief] at the very heart of things.")

professional accoutrements--"brilliant scintillating objects, made to amuse"--and the wretchedness of his condition as an impoverished, vagabond laborer living on the fringes of society, enduring a "life of infinite sadness, if seen from slightly above." From that contrast came another equally eye-opening realization: "I saw quite clearly that the 'Clown' was me, was us, nearly all of us.... This rich and glittering costume, it is given to us by life itself, we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume...." (Rouault summed up this vision in several studies entitled "Sunt Lacrymae Rerum"--"There are tears [of grief] at the very heart of things.")

From that moment on, the clown, as well as other circus figures and denizens of the disreputable periphery of society, haunted Rouault's imagination and art, becoming one of his signature icons. An icon of what? Of the painful disconnection between appearances and reality, between who we are on the inside and who we pretend to be, or what society judges us to be, on the outside. Rouault confronts us on the one hand with clowns and prostitutes, whose real (if battered and buried) human dignity nonetheless still emits some light from within their souls, and on the other hand with the furthest extreme of the social spectrum: the rich, the well-born, the powerful, the "glitterati," wearing the masks of their expensive clothes and polished manners, hiding cruel, narcissistic hearts full of dust and ashes. (See, for example, Rouault's "The Accused" of 1907 and "Superman" of 1916). In his professional life Rouault knew this type well, for it was and is a familiar figure in the upper echelons of the art establishment. His own art dealer, the unsavory but hugely successful Ambroise Vollard, certainly seems to have been of that ilk.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Rouault's death, the McMullen Museum at Boston College has mounted a magnificent, comprehensive review of his prodigiously productive career, Mystic Masque: Semblance and Reality in Georges Rouault, 1871-1958, on view until Dec. 7. This landmark exhibition features over 180 works from every period of the artist's life, some never before seen in the United States. The exhibition was boldly conceived and curated by Stephen Schloesser, S.J., of the Boston College History Department, who also edited an ample and illuminating catalog that features interdisciplinary contributions from more than 20 scholars.

The key word is "masque," meaning both "theatrical face cover" and "masked pageant" (think of Edgar Allan Poe's "Masque of the Red Death"). Not only in his clown paintings, but everywhere in his art, Rouault explores--and provokes his viewers into exploring--the private human reality behind the public mask in order to expose the soul. In that exposure, the high and mighty are reduced to the level of the risible, if not the pathetic (as in his 1927 aquatint, "As proud of her noble stature as if she were still alive"), while the lowly are made to shine in their inherent human dignity. Again, as the artist himself explained to Schuré: "I have the defect...of leaving no one his glittering costume, be he king or emperor. I want to see the soul of the man in front of me...and the greater he is, the more mankind glorifies him, the more I fear for his soul." In Schloesser's view, "Rouault felt compelled to unmask society's well-respected and well-born, and to raise up society's lowly and overlooked." In other words, Rouault's art comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable. It is an art that a Peter Maurin or a Dorothy Day would assuredly have cherished.

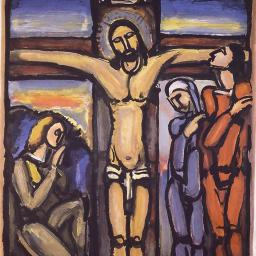

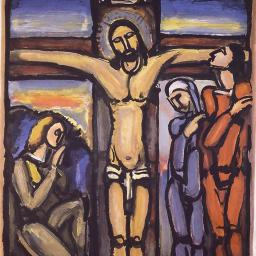

With his fertile imagination and years of productivity, Rouault treated many different themes beyond clowns and masks and employed a variety of media and styles. A revelation for me, and, I suspect, for many viewers, is the Rembrandt-inspired style of his earliest period, represented in the exhibition by two stirring canvases, "The Way to Calvary" and "Job." But perhaps his most enduring stylistic trademark is the use of richly luminous colors gleaming forth from a heavy matrix of thick black lines, clearly the influence of his youthful apprenticeship with stained-glass makers. The exhibition includes one actual stained-glass window by Rouault, a crucifixion scene, and it is simply a gem in the literal sense of that word.

With his fertile imagination and years of productivity, Rouault treated many different themes beyond clowns and masks and employed a variety of media and styles. A revelation for me, and, I suspect, for many viewers, is the Rembrandt-inspired style of his earliest period, represented in the exhibition by two stirring canvases, "The Way to Calvary" and "Job." But perhaps his most enduring stylistic trademark is the use of richly luminous colors gleaming forth from a heavy matrix of thick black lines, clearly the influence of his youthful apprenticeship with stained-glass makers. The exhibition includes one actual stained-glass window by Rouault, a crucifixion scene, and it is simply a gem in the literal sense of that word.

Rouault uses the same stained-glass-inspired style to perhaps its most memorable effect in

his many depictions of the "Holy Face," the face of the suffering Jesus as traditionally seen in representations of the sudarium of St. Veronica, which, according to pious belief, shows the true likeness of Christ. The face of Christ is an almost obsessive visual leitmotif for Rouault, a potent symbol of the suffering of an innocent humanity oppressed by an unjust society.

his many depictions of the "Holy Face," the face of the suffering Jesus as traditionally seen in representations of the sudarium of St. Veronica, which, according to pious belief, shows the true likeness of Christ. The face of Christ is an almost obsessive visual leitmotif for Rouault, a potent symbol of the suffering of an innocent humanity oppressed by an unjust society.

Another disturbing existential question is raised by Rouault's art, most literally in the title he gives to several of his works: "Are we not all slaves?" Here Rouault is speaking from bitter personal experience. In 1917, desperately poor and with a family to support, he was forced into what was essentially indentured servitude to that same infamous art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, or Fifi Voleur (Fifi the Thief) as Gauguin called him, a cunning businessman whose ambiguous personal life had much to hide, as Christopher Benfey has probingly written for the online magazine Slate.

Those who prefer art that presents only what Charles Baudelaire would call "la vie en beau" (the pretty side of life) or who shun the examination of conscience might not fully savor this exhibition, but Rouault's style is so visually compelling that it will certainly arrest anyone's attention and ultimately give delight on some level. For many viewers, I dare say, questions surrounding the moral life, social justice, sincerity and authenticity will likely dominate their response to this exhibition, as they dominated Rouault's artistic imagination and as they dominate the conception of the exhibition itself.

Rouault is probably familiar to anyone who went through the parochial school system in the United States. My own introduction to "Rouault the Catholic artist" occurred many years ago at Cardinal Hayes High School in the Bronx. Yet Rouault himself (a true believer, albeit not of the orthodox kind) rejected the very notion of sacred art or the "Catholic artist." "There is no sacred art," he has been quoted as having said. "There is just art pure and simple." Nonetheless, Rouault's work not only has the power to please the eye and feed the mind, but to quicken our attention to the moral and spiritual dimension of human experience and to help move us to a higher plane of consciousness.

Our sensibilities are heightened,our sense of peace is frequently threatened. Violence erupts so easily these days that it's hardly news anymore. Being spat on would likely enrage me and I would hope that I could remain calm. But who knows. I pray for peace in my morning offering, at Mass and whenever I hear a news report revealing any insane act of violence (which is a million times a day). How do we engage pugnacious youth to to live in peace? Do we turn the other cheek? How and why? How do the Franciscan friars live in the Holy Land day after day in the middle of violence and remain at peace with their vocation?

Our sensibilities are heightened,our sense of peace is frequently threatened. Violence erupts so easily these days that it's hardly news anymore. Being spat on would likely enrage me and I would hope that I could remain calm. But who knows. I pray for peace in my morning offering, at Mass and whenever I hear a news report revealing any insane act of violence (which is a million times a day). How do we engage pugnacious youth to to live in peace? Do we turn the other cheek? How and why? How do the Franciscan friars live in the Holy Land day after day in the middle of violence and remain at peace with their vocation?