The Stations of the Cross, also called the Way of the Cross or the Via Dolorosa (Latin for "Way of Sorrow"), are the prevailing popular devotion during Lent but many Catholics made the Stations of the Cross on Fridays throughout the year and some even daily. (Pope John Paul II had the pious practice of making the Stations of the Cross daily and installed a set of stations in the apostolic apartments.) In using the word "stations" we understanding it to come from the Latin "station," meaning "standing still." The Stations are designed to have 14 stops (and some more recent publications include a 15th station) that portray events of the Passion and death of Our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. They begin with Jesus' condemnation to death, and concluding with His being laid in the tomb.

The Stations of the Cross are rooted in the ancient tradition of the Church.

In 1342 the Franciscans became custodians of many of the sacred places in the

Stations are found in every church, reflecting Christ's words: "If any one wishes to come after Me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow Me" (Luke 9:23).

So what's the Church's teaching on the Via Crucis (Way of the Cross)?

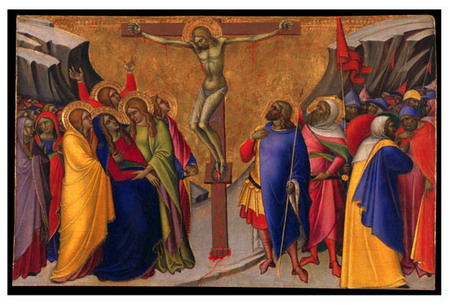

Of all the pious exercises connected with the veneration of the Cross, none is more popular among the faithful than the Via Crucis. Through this pious exercise, the faithful movingly follow the final earthly journey of Christ: from the Mount of Olives, where the Lord, "in a small estate called Gethsemane" (Mk 14, 32), was taken by anguish (cf. Lk 22, 44), to Calvary where he was crucified between two thieves (cf. Lk 23, 33), to the garden where he was placed in freshly hewn tomb (Jn 19, 40-42).

The love of the Christian faithful for this devotion is amply attested by the numerous Via Crucis erected in so many churches, shrines, cloisters, in the countryside, and on mountain pathways where the various stations are very evocative.

The Via Crucis is a synthesis of various devotions that have arisen since the high middle ages: the pilgrimage to the Holy Land during which the faithful devoutly visit the places associated with the Lord's Passion; devotion to the three falls of Christ under the weight of the Cross; devotion to "the dolorous journey of Christ" which consisted in processing from one church to another in memory of Christ's Passion; devotion to the stations of Christ, those places where Christ stopped on his journey to Calvary because obliged to do so by his executioners or exhausted by fatigue, or because moved by compassion to dialogue with those who were present at his Passion.

In its present form, the Via Crucis, widely promoted by St. Leonardo da Porto Maurizio (+1751), was approved by the Apostolic See and indulgenced, consists of fourteen stations since the middle of seventeenth century.

The Via Crucis is a journey made in the Holy Spirit, that divine fire which burned in the heart of Jesus (cf. Lk 12, 49-50) and brought him to

In the Via Crucis, various strands of Christian piety coalesce: the idea of life being a journey or pilgrimage; as a passage from earthly exile to our true home in Heaven; the deep desire to be conformed to the Passion of Christ; the demands of following Christ, which imply that his disciples must follow behind the Master, daily carrying their own crosses (cf Lk 9, 23).

The following may prove useful suggestions for a fruitful celebration of the Via Crucis:

-the traditional form of the Via Crucis, with its fourteen stations, is to be retained as the typical form of this pious exercise; from time to time, however, as the occasion warrants, one or other of the traditional stations might possibly be substituted with a reflection on some other aspects of the Gospel account of the journey to Calvary which are traditionally included in the Stations of the Cross;

-the traditional form of the Via Crucis, with its fourteen stations, is to be retained as the typical form of this pious exercise; from time to time, however, as the occasion warrants, one or other of the traditional stations might possibly be substituted with a reflection on some other aspects of the Gospel account of the journey to Calvary which are traditionally included in the Stations of the Cross;

-alternative forms of the Via Crucis have been approved by Apostolic See or publicly used by the Roman Pontiff: these can be regarded as genuine forms of the devotion and may be used as occasion might warrant;

-the Via Crucis is a pious devotion connected with the Passion of Christ; it should conclude, however, in such fashion as to leave the faithful with a sense of expectation of the resurrection in faith and hope; following the example of the Via Crucis in Jerusalem which ends with a station at the Anastasis, the celebration could end with a commemoration of the Lord's resurrection (131-134).

(Directory on Popular Piety and the Liturgy, 2001)

Leave a comment