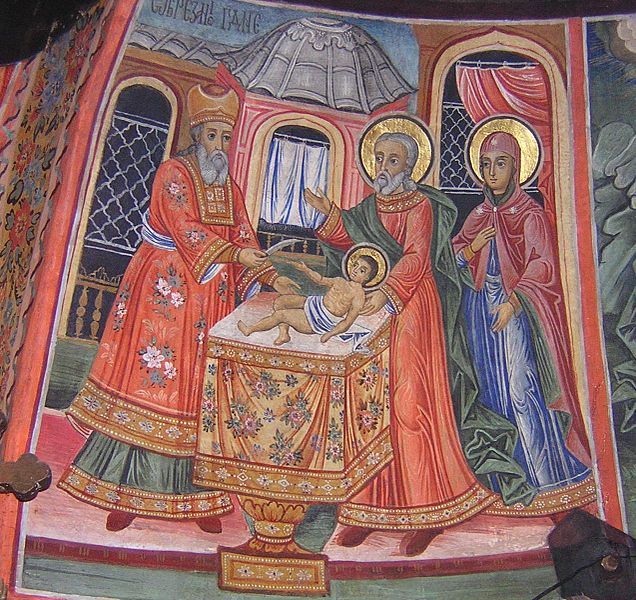

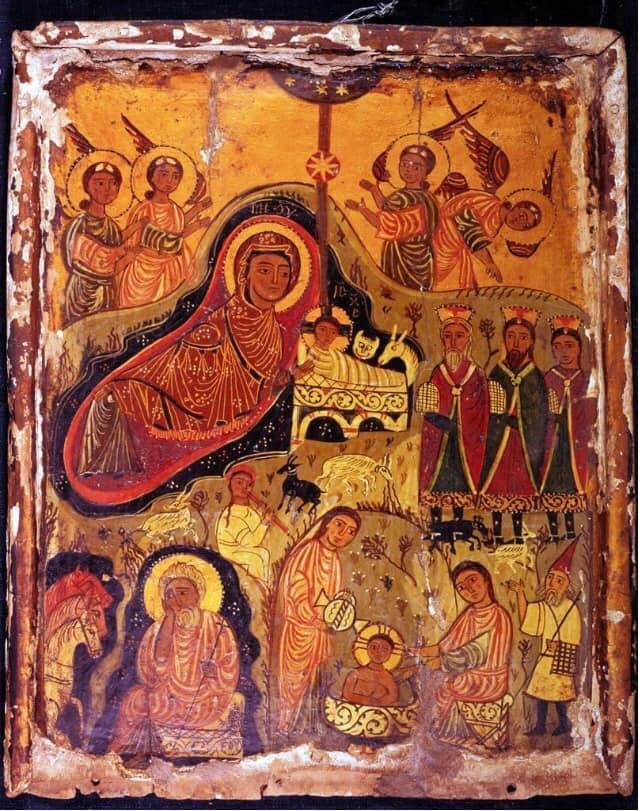

Two feasts to note today: the Circumcision of Our Lord and St. Basil the Great, our father among the saints, archbishop of Caesarea in Cappadocia.

The Byzantine Church followed the civil reckoning of the new year which in Constantine’s day began on September 1st. We liturgically observe the beginning of the year today.

Mosaic law prescribed circumcision on the eighth day after birth, to mark the child as a son of the covenant; at this ritual the name was given: in this case Jesus, or in Hebrew Yeshua, meaning “he who saves”. [As side note, the Latin Church has this feast, too, but it is now obscured in the Novus Ordo, yet it is more prominent in the TLM. The feast with the TLM has several names.]

Basil lived in Cappadocia, the central part of present-day Turkey, during the 4th century. His family had rank and wealth. His mother, Nona, sister, Macrina, and brothers are all honored as saints. Macrina exerted a strong influence on Basil’s early interest in monasticism. Later he traveled through Egypt and Syria to learn more. His impressions were not all positive. He went to Athens to complete his education, and there he met Gregory of Nazianzus who became his best friend. Around the year 356 they applied their classical scholarship to articulate the theory of monastic life. Basil’s various writings, often called “rules” in Western editions, formed a landmark in monastic history.

In 370 Basil was elected bishop of Caesarea. He laid the groundwork for the 2nd Ecumenical Council which completed and confirmed the Nicene Creed. His long and heated battles with the Arians exhausted him and nearly cost him the friendship of the two Gregories: his brother, whom he made bishop of Nyssa, and his school friend, whom he duped into accepting ordination. Though unwilling allies, Basil’s choice assured the establishment of Orthodoxy after his death on this day in 379.

A rich canon of writings have come down to us from Basil, including prayers found in the Office and a Eucharistic Liturgy. (NS)

Happy New Year’s, blessings for 2021!