In preparation for the feast of Saint Benedict today, Sunday, July 11, the Benedictine Primate of the Confederation of Benedictines, Abbot Gregory, reflects on the wisdom of Saint Benedict.

It was published in today’s Osservatore Romano: https://bit.ly/3AOTlPS

________

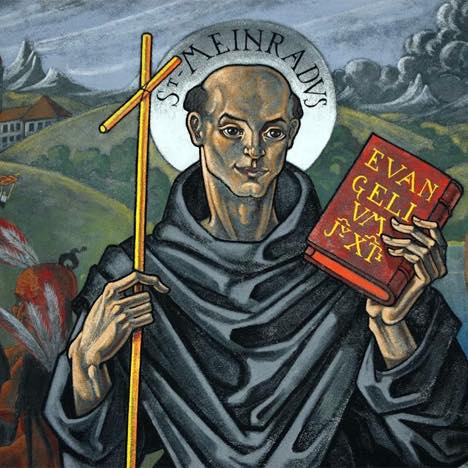

Saint Benedict: A Wise Guide for Living Well TodayAbbot Primate Gregory Polan, O.S.B.

Can a text which dates back 1,500 years be practical for living well today? The Rule of Saint Benedict stands as a classic text of spiritual insight and humane behavior. Such classic texts often give us a brief word which has much to say to us. We live in a world and a culture that bombards us with words. Often there are so many words that shower and flood us each day that we have little or no time to take in their meaning and impact. The early monastic tradition understood the value of well-chosen and well-spoken words, as well as silence. In a moment of excitement or reaction to the comments of someone, how often have we regretted our immediate or less measured response? While we may have a well cultivated language, we often have a less cultivated sense of what is best left unspoken, or said in a measured and reflective way.

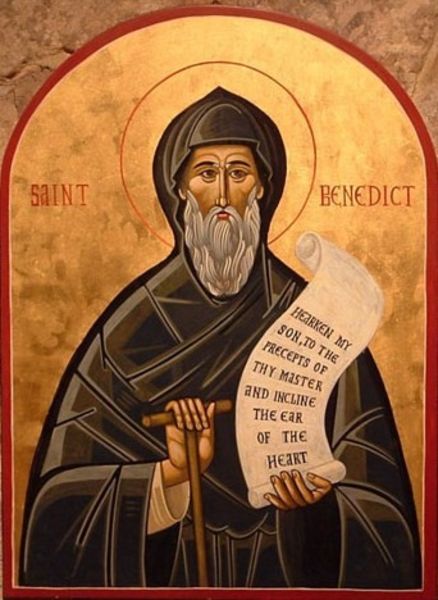

The opening words of The Rule of Saint Benedict offer an instruction that calls for an interior discipline. The text of the Prologue to the Rule reads, “Listen carefully, my child, to the master’s instructions, and attend to them with the ear of your heart.” As language has developed through the centuries, so have the number of words and their distinct nuances. The more words that bombard our hearing, the less intent we are in carefully appreciating their meaning, their impact, and their power. Yet in contrast to this, a few words, well spoken can touch the heart, lift the human spirit, transform the mind, give direction in life’s choices, and remain within us as a guide to fruitful Christian living.

We can carefully distinguish the difference between “hearing” and “listening.” We can hear words that are spoken; and they quickly pass on, often unnoticed and hardly considered. In contrast to this, when we truly listen to what a person is saying, this act implies our reflection on the impact of what is said, a careful consideration or rumination on the impact and meaning of these words. If we are truly listening with the ear of the heart, these words pass from the ear to the mind and to the heart. Often when we honestly listen to what is said, it asks something of us. Should I ponder these thoughts more seriously, question my motivations for what I am doing, reconsider what I am doing? And sometimes this contemplation assures me of the values I am trying to live. That command to ponder seriously is how Saint Benedict begins his Rule; this initial command serves as motto for the monastic life, “to listen with the ear of the heart.” But isn’t that also an invitation to anyone of us in the movement of our lives, our daily living?

In the Scriptures, particularly in the Old Testament, the heart was understood to encompass a process and reflection of both the mind and the heart together, working in tandem. This was understood to be an endeavor of the whole interior of a person. Too often our reactions arise from an initial thought that comes to mind; rather, to begin with thoughts of the mind and then to reflect from the posture of the heart brings together a better and fuller expression of what is best. “What does this mean … what are the implications of what is being said … how does this challenge me to think differently?” Saint Benedict could challenge us in our own day to take on this process of “listening with the ear of the heart” in our decision making, in our relations with one another, and in our responses to the variety of situations and questions that come before us. What a difference this would make on every level of our human existence: within the family unit, within a business operation, among families and friends, among world leaders, among warring nations, among countries seeking peaceful resolutions.

Pope Francis presents to us an important challenge with his announcement of the forthcoming Synod of Bishops; the focus will be on creating a synodal process for the Church as it moves into the future. One of the key elements which can have an impact on this process of involving the whole Church in this endeavor is the act of listening. And Saint Benedict has something very worthwhile to offer to this – that this process will include a “listening with the ear of the heart,” as he begins his Rule. This calls for a great humility and openness to what another has to say, to offer as a suggestion, to seek a peaceful resolution. Could this person be an instrument of God’s will being manifested to us? A synodal process calls for great sincerity and a true sense of listening deeply, profoundly, lovingly, openly, and receptively.

This year the feast of Saint Benedict, one of the patrons of Europe, falls on Sunday, 11 July. His teaching in the Rule offers us a profound way of renewing our hearts through the manner of our listening – that is, whole heartedly. Imagine the blessings of peace and hope that could resound throughout the world if his instructions on the manner of our listening to one another could become a reality. Whether this special kind of listening is between struggling nations, warring political parties, religious leaders, and even within families, our ability of listen with a depth of respect for one another as children of God holds the promise of peace and blessing for all. Even in our day-to-day lives, “listening with the ear of the heart” holds out to us the promise of peace and hopes as we move forward into each new day. Saint Benedict, pray for us; help us to listen to one another with the ear of our heart (“Prolog 1, The Rule of Saint Benedict).