This article by Jesuit Father John Belmonte on lectio divina is helpful for coming to know the Lord. Lectio is a place of encounter with the Lord and it is in lectio we come to know and love Him in whom and by whom we are saved.

Talk show host Jay Leno has a very funny segment on his “Tonight Show” where he interviews the “man on the street,” testing people’s knowledge in a given subject matter. Rare is the person who does well. On one occasion, he asked questions about a topic that keenly interests me: the Bible. While the survey was hardly scientific, the questions were very basic. No historical-critical method here. “Name one of the Ten Commandments,” Jay asked. “Freedom of speech,” a man unhesitatingly responded. “Name the four Gospels,” Jay asked. With a befuddled look, a woman was unable to answer. “Name the four Beatles,” Jay asked. Without any hesitation and a relieved smile, the woman responded, “John, Paul, George, and Ringo.” My personal favorite was the man whom he asked, “In the Old Testament, who was swallowed by the whale?” He looked directly into the camera and, as serious as death, said, “Pinocchio.”

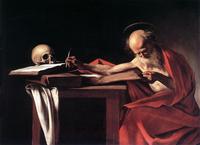

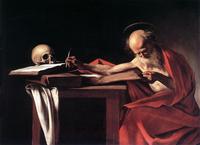

As someone who has taught Scripture to high school students, these answers did not surprise me. Religious educators and biblical scholars regularly decry a growing lack of familiarity with Scripture. Catholic ignorance of the Bible is proverbial. A study of 508 teenagers by the Princeton Religion Research Center confirmed that Catholic young people are much less familiar with Scripture than their Protestant counterparts. Even more distressing is the finding that thirty percent said that they never even opened the Bible. If Saint Jerome’s axiom, “Ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ,” is true, then those of us who are full members of the Catholic Christian community have a serious situation on our hands. Isn’t it incumbent upon us to pass on the tradition, to introduce others to the living God, to dispel ignorance of the Word of God? If not us, then who?

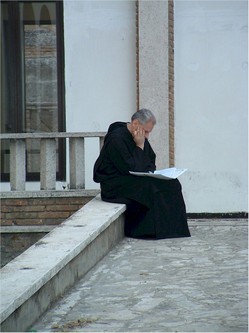

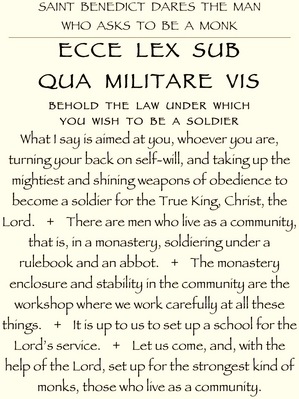

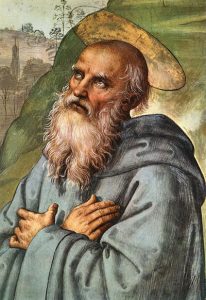

Even amid the decline in elementary biblical knowledge, help is on the way. Vatican II did much to help revive interest in Scripture, and one method that may help bridge the gap Mr. Leno so cleverly pointed out is the ancient monastic method of reading the Bible called lectio divina. The Latin expression lectio divina does not translate into English with great accuracy. Literally, it means “holy reading within the monastic tradition, and in Saint Benedict’s rule in particular, its meaning is obvious. Lectio divina is an attentive and in-depth reading of the sacred Scriptures intended not simply to satisfy one’s curiosity but to nourish one’s faith. Benedict’s monks were to nourish themselves with the divine food of Scripture in order to have sufficient resources for the journey of faith. In the Rule of Saint Benedict, the monk is exhorted to listen carefully and willingly to holy readings, the lectiones sanctae. The reading is holy because its object is the word of God. Scripture is approached not for scientific or technical reasons but in order to deepen one’s personal commitment to God and God’s Son.

Even amid the decline in elementary biblical knowledge, help is on the way. Vatican II did much to help revive interest in Scripture, and one method that may help bridge the gap Mr. Leno so cleverly pointed out is the ancient monastic method of reading the Bible called lectio divina. The Latin expression lectio divina does not translate into English with great accuracy. Literally, it means “holy reading within the monastic tradition, and in Saint Benedict’s rule in particular, its meaning is obvious. Lectio divina is an attentive and in-depth reading of the sacred Scriptures intended not simply to satisfy one’s curiosity but to nourish one’s faith. Benedict’s monks were to nourish themselves with the divine food of Scripture in order to have sufficient resources for the journey of faith. In the Rule of Saint Benedict, the monk is exhorted to listen carefully and willingly to holy readings, the lectiones sanctae. The reading is holy because its object is the word of God. Scripture is approached not for scientific or technical reasons but in order to deepen one’s personal commitment to God and God’s Son.

Lectio Divina from the Monastery to the Marketplace

All quarters of the church, from official pronouncements to informal movements, have in recent times repeatedly affirmed the need for and effectiveness of lectio divina. There are many ways in which one can encounter God through the biblical word. Yet, the rich history, significant connection to tradition, genuine spirituality, and pastoral applicability of lectio divina make it a particularly attractive method.

Lectio divina is one instrument of grace by which we encounter Christ in the Scriptures. When practiced every day, lectio divina fosters the kind of contact with God’s word that, over the course of a lifetime, promises a life of prayer lived out in faithful love. To suggest that a specific method for lectio divina might be necessary carries with it a risk. In our practice of this method, we might be tempted to follow rigidly the proposals offered as rules and not as suggestions. To do so would be a mistake. What lectio divina demands in the first place is an openness to the Spirit, which any master of the spiritual life would see as a prerequisite to prayer. Ignatius of Loyola’s instruction in his Spiritual Exercises to those who intend to pray is a good example. He suggests that believers must always pray “with great spirit and generosity toward their Creator and Lord.” Balance and flexibility are very important as one begins to practice lectio divina. We should always avoid rigidity, excessive formalism, or forcing things. My intention is not that the suggested schema that follows be realized as a fixed program; lectio divina is a way to encounter God, and we should always feel free to utilize it according to our own rhythms, gifts, and desires.

Lectio divina is one instrument of grace by which we encounter Christ in the Scriptures. When practiced every day, lectio divina fosters the kind of contact with God’s word that, over the course of a lifetime, promises a life of prayer lived out in faithful love. To suggest that a specific method for lectio divina might be necessary carries with it a risk. In our practice of this method, we might be tempted to follow rigidly the proposals offered as rules and not as suggestions. To do so would be a mistake. What lectio divina demands in the first place is an openness to the Spirit, which any master of the spiritual life would see as a prerequisite to prayer. Ignatius of Loyola’s instruction in his Spiritual Exercises to those who intend to pray is a good example. He suggests that believers must always pray “with great spirit and generosity toward their Creator and Lord.” Balance and flexibility are very important as one begins to practice lectio divina. We should always avoid rigidity, excessive formalism, or forcing things. My intention is not that the suggested schema that follows be realized as a fixed program; lectio divina is a way to encounter God, and we should always feel free to utilize it according to our own rhythms, gifts, and desires.

Having pointed out the importance of some prerequisites to lectio divina, such as balance,

openness, and flexibility, a word is in order about the structure or steps that this ancient practice usually takes. Much has been written about these steps, but the most exhaustive and perhaps best-known example comes from Guigo II (1115-1198), the Cistercian prior at Chartres from 1173 to 1180. In his “Letter on the Contemplative Life,” also known as Scala Claustralium, Guigo gives the classic four-part expression to the lectio divina: lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio. Since Guigo’s text has become a nearly obligatory point of reference for someone considering lectio divina, it seems appropriate to reproduce here a brief summary citation from the letter:

openness, and flexibility, a word is in order about the structure or steps that this ancient practice usually takes. Much has been written about these steps, but the most exhaustive and perhaps best-known example comes from Guigo II (1115-1198), the Cistercian prior at Chartres from 1173 to 1180. In his “Letter on the Contemplative Life,” also known as Scala Claustralium, Guigo gives the classic four-part expression to the lectio divina: lectio, meditatio, oratio, and contemplatio. Since Guigo’s text has become a nearly obligatory point of reference for someone considering lectio divina, it seems appropriate to reproduce here a brief summary citation from the letter:

One day during manual labor, as I was beginning to reflect on the spiritual exercise of man, suddenly four spiritual steps appeared to my mind: reading, meditation, prayer, and contemplation. This is the ladder of the monks by which they are elevated from the earth to heaven and even though it may be formed by only a few steps, nevertheless it appears in immense and incredible greatness. The lower part rests on the earth; however, the higher part penetrates the clouds and scrutinizes the secrets of the heavens.

Now the reading consists in the attentive observation of the Scriptures with one’s spirit applied. The meditation is the studious action of the mind, which seeks the discovery of hidden truth by means of one’s own intelligence. The prayer consists in a religious application of the heart of God in order to dispel evil and obtain favors. The contemplation is an elevation into God, from the mind attracted beyond itself, savoring the joys of eternal sweetness….

Reading seeks the sweetness of the blessed life, while meditation finds it. Prayer asks for it and contemplation tastes it. Reading, in a certain way, brings solid food to the mouth, meditation chews and breaks it up, prayer obtains its seasoning, contemplation is the same sweetness which refreshes and brings joy.

Guigo sets down a four-part method, but for our purposes we will reduce that structure to three: lectio, meditatio, and oratio. The reason for collapsing the final two steps into one is simple. Prayer is at the core of the way the two final steps are conceived. By collapsing them into a third phase, we respect the progression that naturally develops from the first two steps. However, we leave open the possibility of expanding on the process of prayer by adding three more steps: discretio, deliberatio, and actio. Some critics object to any tinkering with the traditional structure of lectio divina. Even so, a brief look at the historical development of the method over the centuries shows that one can understand Guigo’s four steps as an expression of the monastic world of his time. Our minor change should be viewed in the same light.

The Practice of Lectio Divina

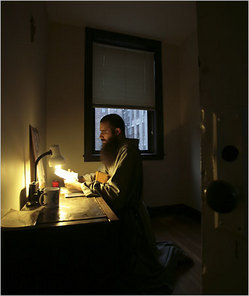

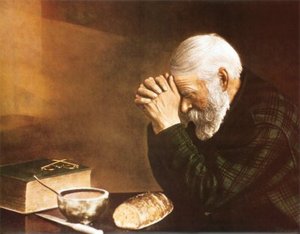

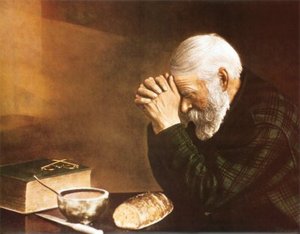

The first thing necessary to practice lectio divina should be obvious: time. As with anything worth doing or any relationship worth maintaining, the practice of lectio divina must be worth spending time doing. While we should avoid the kind of rigidity described above, the spiritual life does demand a certain amount of healthy discipline. Whether we want to fix a regular time, a certain period, or the most effective time, regularity is important. Our time is a precious thing, and offering it to God is a very simple and concrete first step toward our meeting God in prayer.

Equally obvious but also quite necessary to consider is which text to use for lectio divina. Our emphasis in lectio divina remains squarely with the biblical text. It is possible to substitute other texts for biblical texts; however, we should not lightly forfeit the surpassing value of reading, meditating, and praying with what the Fathers called the sacra pagina. Jerome himself reminds us that “the text presents itself simply and easily in words, but in the greatness of its meaning, its depth is unfathomable.”

Equally obvious but also quite necessary to consider is which text to use for lectio divina. Our emphasis in lectio divina remains squarely with the biblical text. It is possible to substitute other texts for biblical texts; however, we should not lightly forfeit the surpassing value of reading, meditating, and praying with what the Fathers called the sacra pagina. Jerome himself reminds us that “the text presents itself simply and easily in words, but in the greatness of its meaning, its depth is unfathomable.”

Related to our emphasis on the biblical text itself is the presupposition that lectio divina is a continuous reading of the whole Bible. In our practice of lectio divina, we should avoid the temptation to select texts well suited to topics chosen in advance. By attending to the whole of Scripture, as the liturgy does in the lectionary, we preserve the context of biblical revelation, both the Old and New Testament. We must avoid the risk of allowing the lectio to “overflow the riverbanks of the tradition and the church,” as Cardinal Martini has written. Practicing lectio divina within the context of the whole of biblical revelation emphasizes the unity of Scripture and our belief in the Bible’s inspiration by God. Moreover, emphasis on the unity of Scripture allows us to avoid the temptation of placing Scripture at the service of ideology or subjectivism.

Time set aside for God should take on a dimension different from the rest of one’s day. To help mark that moment, most spiritual masters suggest that the person who sets out to pray begin by making some kind of epiclesis, which is an invocation or “calling down” of the Holy Spirit to consecrate. In the Eucharist, we call down the Spirit upon the bread and wine to transform them into the body and blood of Christ. As we begin lectio divina, we should remind ourselves that it is through the work of God in the Spirit that the written word is transformed in our lives into the living word.

Time set aside for God should take on a dimension different from the rest of one’s day. To help mark that moment, most spiritual masters suggest that the person who sets out to pray begin by making some kind of epiclesis, which is an invocation or “calling down” of the Holy Spirit to consecrate. In the Eucharist, we call down the Spirit upon the bread and wine to transform them into the body and blood of Christ. As we begin lectio divina, we should remind ourselves that it is through the work of God in the Spirit that the written word is transformed in our lives into the living word.

The Four Steps of Lectio Divina: Lectio, Meditatio, Oratio, Actio

Having set aside the time, “selected” the text, and invoked the Spirit, we are ready to begin the first formal step of lectio divina, called the lectio. This is the moment in which we read and reread a passage from the Old or New Testament, alert to its most important elements. The operative question is, What does the text say? Patient attentiveness to what the text has to say characterizes our stance before it. We should read the text for itself, not to get something out of it, like a homily, a conference, or a catechism lesson. The word of God should be allowed to emerge from the written word.

In lectio, each person’s experiences and talents before the text come into play. The more experience or education one has, the more one will potentially bring to the text. Knowledge of biblical languages or an understanding of theology can also enrich one’s reading. Consultation of available biblical commentaries or dictionaries can be especially helpful as we attempt to expand our understanding about what the text is saying. Paying attention to grammar, the usage of words, and the relationships of verbs to nouns or of subjects to objects can make the text begin to take on new and unexpected significance.

The second step, called the meditatio, is equally important. We leave behind the specifics of the text and focus instead on what is behind it, on the “interior intelligence” of the text, as Guigo puts it. The meditatio is a reflection on the values which one finds behind the text. Here, one must consider the values behind the actions, the words, the things, and the feelings which one finds in a particular scriptural passage. Anyone who honestly seeks God and one’s authentic self in prayer will hear the echoes of joy, fear, hope, and desire coming from the sacred page. The operant question for this stage doesn’t stop at what the text says, but asks, What does the text say to me? We seek to make emerge from history and context the specific message of the text. The shift from external forms to internal content makes this stage an important one.

The second step, called the meditatio, is equally important. We leave behind the specifics of the text and focus instead on what is behind it, on the “interior intelligence” of the text, as Guigo puts it. The meditatio is a reflection on the values which one finds behind the text. Here, one must consider the values behind the actions, the words, the things, and the feelings which one finds in a particular scriptural passage. Anyone who honestly seeks God and one’s authentic self in prayer will hear the echoes of joy, fear, hope, and desire coming from the sacred page. The operant question for this stage doesn’t stop at what the text says, but asks, What does the text say to me? We seek to make emerge from history and context the specific message of the text. The shift from external forms to internal content makes this stage an important one.

The meditatio is an activity that engages our intellect. As we pass from the second to the third stage of lectio divina, we move more into the realm of religious emotions. Remaining on an intellectual level can be safe and comfortable, but the goal of prayer is not knowledge about God, but God himself. In the oratio, our imagination, will, and desires are engaged as we seek union with God. Oratio in its most fundamental sense is dialogue with God. Gregory the Great called it “the spontaneous meeting of the heart of God with the heart of God’s beloved creature through the word of God.”

When we progress from meditatio to oratio, an immediate experience of infused mysticism is hardly to be expected. Mystical union with God is not necessarily an ordinary part of Christian life. Nevertheless, the passage from meditatio to oratio is the vital and decisive moment of Christian experience. The more deeply we enter the oratio, the more we move beyond the text, beyond words and thoughts. The lectio is useful and the meditatio is important since they lead us to the oratio, which is life in its fullest sense, the life of Christ that he lives in the one who contemplates him. Oratio is the passage from the values behind the text to adoration of the person of Jesus Christ, the one who brings together and reveals every value. Unlike the lectio and meditatio, there is no operant question in the oratio. At its core, oratio is the silent adoration of the creature before the Creator, a rare and miraculous gift.

When the person who practices lectio divina reaches the level of oratio, it would seem that that moment would be conclusive. However, the dynamism of prayer that began during the epiclesis before the lectio is not interrupted here. To the contrary, it naturally continues and the oratio, as we are proposing it here following Cardinal Martini’s insight, possesses its own steps, called discretio, deliberatio, and actio. These three steps represent the way lectio divina is lived out in daily life. Given the growing dissociation of the faith from daily life, these three successive moments take on great significance.

Since the meditatio intends to put one in contact with the values of Christ, to encourage our identification with those things that are important to Christ, we naturally come to moments of decision. The discretio is the capacity that the Christian acquires through grace to make the same choices as Christ. Cardinal Martini describes discretion like this: “It is the discernment of that which, in a determined historical moment, is best for oneself, for others, and for the church.”

The second moment of the oratio is called the deliberatio. It is an interior act by which one decides in favor of the values of the gospel. One chooses to associate oneself with Christ and everything that association represents–in a word, discipleship. If the discretio is described as the capacity of a person to choose, then the deliberatio is the choice itself.

The final moment is called actio. In this final step, the choice we make in the deliberatio is given form and substance. Prayer becomes something more than simply setting aside time for God or an attempt to better ourselves. Our lives begin to take shape from the choices we have made as a result of prayer. The actio is the integration of a kind of apostolic consciousness that informs our choices so that we have made and lived our choices from our encounter with the living God.

Some critics would leave these last steps, particularly the actio, out of any proposed lectio divina. The addition of an extra step suggests perhaps overzealousness or even the influence of an “ideology of efficacy” regarding one’s prayer. Too often we feel we need to make prayer into something. However, in the face of a modern world in which the outward signs of the mystery of God are ever more difficult to recognize, where a daily experience of gospel or even transcendent values becomes harder to find, and where choices besiege one’s conscience and stifle rather than uplift the Spirit, this criticism is unconvincing. If anything, the connection between prayer and our life choices should become more explicit, not less. The faith, hope, and love made manifest in the choices our lives become must be nourished by contact with the word of God.

Some critics would leave these last steps, particularly the actio, out of any proposed lectio divina. The addition of an extra step suggests perhaps overzealousness or even the influence of an “ideology of efficacy” regarding one’s prayer. Too often we feel we need to make prayer into something. However, in the face of a modern world in which the outward signs of the mystery of God are ever more difficult to recognize, where a daily experience of gospel or even transcendent values becomes harder to find, and where choices besiege one’s conscience and stifle rather than uplift the Spirit, this criticism is unconvincing. If anything, the connection between prayer and our life choices should become more explicit, not less. The faith, hope, and love made manifest in the choices our lives become must be nourished by contact with the word of God.

Conclusion

Lectio divina is one graced instrument to bridge the gap that exists between our hearts and God’s. As the faith risks being further dissociated from daily life, the simplicity and potential of a method like lectio divina take on greater significance. Firmly rooted in the church’s tradition, it presumes careful attention to what biblical specialists are thinking and teaching. Rigorous study is complemented by disciplined meditation and prayerful contemplation of the word of God. Far from being an objective or rigid technique whereby one produces religious experience, lectio divina represents daily contact with God’s word that occurs within a lifetime’s engagement with the Living God. The principal aim of such engagement is to foster living prayer in faithful love. Lectio divina unfolds more than it proceeds; progresses and develops more than it advances.

Lectio divina is one graced instrument to bridge the gap that exists between our hearts and God’s. As the faith risks being further dissociated from daily life, the simplicity and potential of a method like lectio divina take on greater significance. Firmly rooted in the church’s tradition, it presumes careful attention to what biblical specialists are thinking and teaching. Rigorous study is complemented by disciplined meditation and prayerful contemplation of the word of God. Far from being an objective or rigid technique whereby one produces religious experience, lectio divina represents daily contact with God’s word that occurs within a lifetime’s engagement with the Living God. The principal aim of such engagement is to foster living prayer in faithful love. Lectio divina unfolds more than it proceeds; progresses and develops more than it advances.

Dedicated practice engages the whole person–the intellect as well as the imagination, the will as well as the affect. It promises contact with God that is the normal fulfillment of prayer. Lectio divina is open to every person and not the exclusive property of a select few. Those who practice lectio divina reaffirm the belief that the proper place for the word of God is in the hands of the faithful.

Wouldn’t Geppetto have been pleased if, instead of his firm response, “Pinocchio,” that young man had looked into Jay Leno’s TV camera and answered with conviction, “Jonah”?

Reprinted from Chicago Studies 39 (2000): 211-19.

Let the whole multitude of the faithful exult in the glory of our beloved Father Benedict; but most of all let that army of monks be glad who on earth are celebrating the feast of him with whom the Saints in heaven are rejoicing. (Magnificat antiphon)

Let the whole multitude of the faithful exult in the glory of our beloved Father Benedict; but most of all let that army of monks be glad who on earth are celebrating the feast of him with whom the Saints in heaven are rejoicing. (Magnificat antiphon) The abbot also noted for us that Benedict is an example of being “watchful” in the face of grace and sin; he was attentive to sustaining others in the struggle against Satan. One can say, therefore, that Benedict is a living Gospel: he lived the Gospel faithfully and his witness to Christ was substantial. While it seems odd that on a joyous occasion such as this feast to tell people to keep death before our eyes as Benedict admonished his monks, it is nevertheless true that we ought to do so because it is an expression of Christian hope: we desire our destiny, we desire the infinite. As Pope Benedict reminded us in last encyclical, the distinguishing mark of the Christian is that we know we have a future. Just as Saint Benedict was converted, the abbot said, by the Paschal Mystery of the Lord, so by that same Mystery shall we be transformed if we give ourselves over the Lord without reserve.

The abbot also noted for us that Benedict is an example of being “watchful” in the face of grace and sin; he was attentive to sustaining others in the struggle against Satan. One can say, therefore, that Benedict is a living Gospel: he lived the Gospel faithfully and his witness to Christ was substantial. While it seems odd that on a joyous occasion such as this feast to tell people to keep death before our eyes as Benedict admonished his monks, it is nevertheless true that we ought to do so because it is an expression of Christian hope: we desire our destiny, we desire the infinite. As Pope Benedict reminded us in last encyclical, the distinguishing mark of the Christian is that we know we have a future. Just as Saint Benedict was converted, the abbot said, by the Paschal Mystery of the Lord, so by that same Mystery shall we be transformed if we give ourselves over the Lord without reserve.