Our Catholic Faith, I believe, has something important to say to the concerns of post-modernity, especially regarding matters of faith and reason AND faith and the public order. Work –our labor– is one of those things that Catholicism speaks eloquently about. We still live with the legacy of Marx and his kind when it comes to understanding the role and place of work. Contrary to Marxism’s theory of alienation, we would say, human labor does have meaning and there is a dignity to the process of work and the worker.

The following is an excerpt of a 1980 letter sent to the Benedictines by John Paul II on the 1500th anniversary of monastic life. John Paul writes:

Man’s face is often wet with tears impelling him to pray, but these tears do not always spring from sincere compunction or excessive joy. For often tears of sorrow and disturbance ow from those whose human dignity is disregarded, those who cannot achieve what they justly desire, and who cannot do the work that suits their needs and talents.

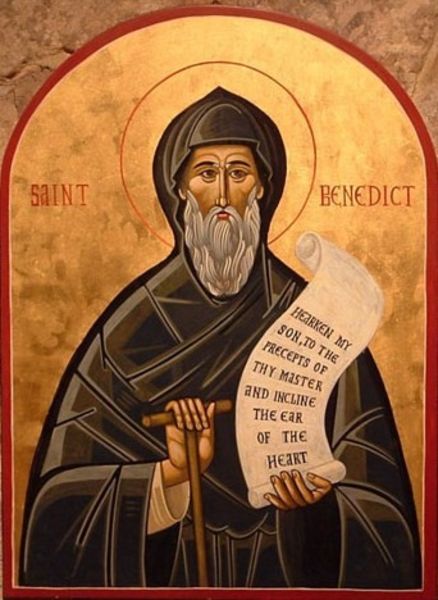

St Benedict lived in a civil society deformed by injustices. The human person frequently counted for nothing and was treated as a criminal. In a social structure drawn up in orders, the most wretched were segregated and reduced to slavery. The poor grew poorer, while the rich grew richer and richer. Yet this remarkable man willed to found the monastic community on the prescriptions of the Gospel. He restored man to his integral condition, no matter what social order or rank he came from. He provided for the needs of each according to the norms of a wise distributive justice. He assigned significant duties to individuals, duties which cohered aptly with other duties. He considered the conditions of the weak, but left no room for easy laziness. He allowed space for the cleverness of others lest they feel hemmed in, or rather, so that they might be stimulated to give their best. Thus he removed the pretext of a light and sometimes justified murmuring, and brought about the conditions of true peace.

Man is not reckoned by St Benedict as a kind of nameless machine, which someone uses to get the maximum profit, providing no moral justification to the worker and denying him a just wage. It should be noted that in his time work was usually done by slaves who were denied the status of human beings. Benedict considered work, however it happens to be done, as an essential part of the life and obliges each monk to it, making it a duty in conscience. This labor is to be borne ‘for the sake of obedience and expiation’, since indeed pain and sweat are attached to any truly efficacious effort. But this distress has a redemptive character when it purifies a man from sin, and it ennobles the things carefully worked on and also the environment where the work is done.

St Benedict, leading an earthly life in which work and prayer were properly balanced, in this way happily inserts work into the supernatural way of considering life. By doing so, he helps man to know himself as God’s fellow-worker, and truly he becomes such when his person, acting with a certain creative energy, is enhanced in an all-round way. Human action is carried out in a contemplative manner, and contemplation attains a certain dynamic quality. It influences the work itself and throws light on the ends proposed for the work.

Work is, therefore, not performed solely in order to avoid the idleness which enfeebles minds, but also and indeed chiefly, to enable a man to grow gradually as a person mindful of his duties and careful about them. Also, talents perhaps concealed deep inside the person may be discovered, and brought to fruition for the common good, ‘so that in all things God may be glorified’.

Work is not relieved of its burden of the harsh clash of forces, but a new interior impulse is added to it. The monk is united to God not in spite of his work but through it, because ‘while working with hand or mind he continually raises himself to Christ’.

Thus it happens that even lowly and insignificant work is done with a certain dignity, and becomes a vital part of ‘that sovereign effort by which God alone is sought in solitude and silence, so that to such a life is added the vigor of continual prayer, the sacrifice of praise, celebrated and consummated together, under the influence of cheerful fraternal charity’.

Europe became a Christian land chiefly because sons of St Benedict gave our ancestors a comprehensive instruction, not only teaching them arts and crafts but also infusing into them the spirit of the Gospel which is needed for the protection of the spiritual treasures of the human person. The paganism which was formerly drawn over to the Gospel by the many hands of missionary monks is now spreading more and more in the Western world, and it is both the cause and the effect of the loss of the Christian way of esteeming work and its dignity.

Unless Christ endows human action with a constant lofty meaning, the worker becomes the slave –a special kind of slave unique to modern times– of profit and industry. On the contrary, Benedict affirms the urgent necessity of giving a spiritual character to work, enlarging the purpose of human labour so that it can escape the excessive application of the technical arts and the excessive greed for what is useful to one’s self.

(An excerpt from Pope St John Paul II’s 1980 Apostolic Letter for the Fifteenth Centenary of the Birth of St Benedict)