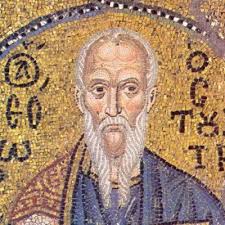

Those who make it a point to study the monastic life have an appreciation for today’s saint, Theodore. Otherwise, Theodore is generally unknown. But he ought not to be. Theodore is liturgically recalled today while the Western Church typically keeps his memorial on November 12. Theodore is a spiritual father, had a concern for the poor and education of the unlettered, he was an author (with his saintly brother), the reformer of the monastic life, a missionary, a fighter against iconoclasm, and seen by those in civil authority an irritant. My own interest is his reform of the monastery and a rule of life that he wrote.

Those who make it a point to study the monastic life have an appreciation for today’s saint, Theodore. Otherwise, Theodore is generally unknown. But he ought not to be. Theodore is liturgically recalled today while the Western Church typically keeps his memorial on November 12. Theodore is a spiritual father, had a concern for the poor and education of the unlettered, he was an author (with his saintly brother), the reformer of the monastic life, a missionary, a fighter against iconoclasm, and seen by those in civil authority an irritant. My own interest is his reform of the monastery and a rule of life that he wrote.

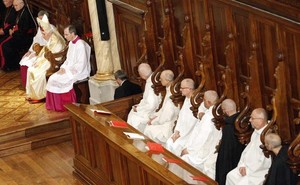

In one typicon we read this biography. Following is a General Audience of Pope Benedict XVI of 27 May 2009 where he give us a beautiful reflection on Theodore. So, I would give all of what’s here some good attention.

“Theodore was born in Constantinople in 759. In his 22nd year he entered a monastery across the Bosporus in Asia Minor. Twelve years later he was elected hegumen. When the spread of Islam threatened the Asian provinces, Theodore moved his community to the safety of the imperial city. He took over the abandoned monastery of Studios. In this urban location, Theodore adjusted the monks’ work to include a school, and a charitable ministry to the city’s poor who pressed at his gates.

“Theodore was an able spiritual father, and a man of strong convictions. As a result, he was sent into exile three times for clashing with the emperor. Along with St John of Damascus, he defended icons in the face of imperial persecution. In monastic history he is remembered for his writings and instructions on the cenobitic life. Theodore stressed the role of obedience, and the importance of the office in the common life. He died in 869. The Typicon of his monastery replaced those of earlier Palestinian fathers as a pattern for subsequent foundations on Athos and in Russia. (NS)

Benedict spoke,

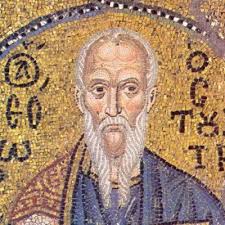

The Saint we meet today, St Theodore the Studite, brings us to the middle of the medieval Byzantine period, in a somewhat turbulent period from the religious and political perspectives. St Theodore was born in 759 into a devout noble family: his mother Theoctista and an uncle, Plato, Abbot of the Monastery of Saccudium in Bithynia, are venerated as saints. Indeed it was his uncle who guided him towards monastic life, which he embraced at the age of 22. He was ordained a priest by Patriarch Tarasius, but soon ended his relationship with him because of the toleration the Patriarch showed in the case of the adulterous marriage of the Emperor Constantine VI. This led to Theodore’s exile in 796 to Thessalonica. He was reconciled with the imperial authority the following year under the Empress Irene, whose benevolence induced Theodore and Plato to transfer to the urban monastery of Studios, together with a large portion of the community of the monks of Saccudium, in order to avoid the Saracen incursions. So it was that the important “Studite Reform” began.

Theodore’s personal life, however, continued to be eventful. With his usual energy, he became the leader of the resistance against the iconoclasm of Leo V, the Armenian who once again opposed the existence of images and icons in the Church. The procession of icons organized by the monks of Studios evoked a reaction from the police. Between 815 and 821, Theodore was scourged, imprisoned and exiled to various places in Asia Minor. In the end he was able to return to Constantinople but not to his own monastery. He therefore settled with his monks on the other side of the Bosporus. He is believed to have died in Prinkipo on 11 November 826, the day on which he is commemorated in the Byzantine Calendar. Theodore distinguished himself within Church history as one of the great reformers of monastic life and as a defender of the veneration of sacred images, beside St Nicephorus, Patriarch of Constantinople, in the second phase of the iconoclasm.

Theodore had realized that the issue of the veneration of icons was calling into question the truth of the Incarnation itself. In his three books, the Antirretikoi (Confutations), Theodore makes a comparison between eternal intra-Trinitarian relations, in which the existence of each of the divine Persons does not destroy their unity, and the relations between Christ’s two natures, which do not jeopardize in him the one Person of the Logos. He also argues: abolishing veneration of the icon of Christ would mean repudiating his redeeming work, given that, in assuming human nature, the invisible eternal Word appeared in visible human flesh and in so doing sanctified the entire visible cosmos.

Theodore and his monks, courageous witnesses in the period of the iconoclastic persecutions, were inseparably bound to the reform of coenobitic life in the Byzantine world. Their importance was notable if only for an external circumstance: their number. Whereas the number of monks in monasteries of that time did not exceed 30 or 40, we know from the Life of Theodore of the existence of more than 1,000 Studite monks overall. Theodore himself tells us of the presence in his monastery of about 300 monks; thus we see the enthusiasm of faith that was born within the context of this man’s being truly informed and formed by faith itself. However, more influential than these numbers was the new spirit the Founder impressed on coenobitic life. In his writings, he insists on the urgent need for a conscious return to the teaching of the Fathers, especially to St Basil, the first legislator of monastic life, and to St Dorotheus of Gaza, a famous spiritual Father of the Palestinian desert. Theodore’s characteristic contribution consists in insistence on the need for order and submission on the monks’ part. During the persecutions they had scattered and each one had grown accustomed to living according to his own judgement. Then, as it was possible to re-establish community life, it was necessary to do the utmost to make the monastery once again an organic community, a true family, or, as St Theodore said, a true “Body of Christ”. In such a community the reality of the Church as a whole is realized concretely.

Another of St Theodore’s basic convictions was this: monks, differently from lay people, take on the commitment to observe the Christian duties with greater strictness and intensity. For this reason they make a special profession which belongs to the hagiasmata (consecrations), and it is, as it were, a “new Baptism”, symbolized by their taking the habit. Characteristic of monks in comparison with lay people, then, is the commitment to poverty, chastity and obedience. In addressing his monks, Theodore spoke in a practical, at times picturesque manner about poverty, but poverty in the following of Christ is from the start an essential element of monasticism and also points out a way for all of us. The renunciation of private property, this freedom from material things, as well as moderation and simplicity apply in a radical form only to monks, but the spirit of this renouncement is equal for all. Indeed, we must not depend on material possessions but instead must learn renunciation, simplicity, austerity and moderation. Only in this way can a supportive society develop and the great problem of poverty in this world be overcome. Therefore, in this regard the monks’ radical poverty is essentially also a path for us all. Then when he explains the temptations against chastity, Theodore does not conceal his own experience and indicates the way of inner combat to find self control and hence respect for one’s own body and for the body of the other as a temple of God.

However, the most important renunciations in his opinion are those required by obedience, because each one of the monks has his own way of living, and fitting into the large community of 300 monks truly involves a new way of life which he describes as the “martyrdom of submission”. Here too the monks’ example serves to show us how necessary this is for us, because, after the original sin, man has tended to do what he likes. The first principle is for the life of the world, all the rest must be subjected to it. However, in this way, if each person is self-centred, the social structure cannot function. Only by learning to fit into the common freedom, to share and to submit to it, learning legality, that is, submission and obedience to the rules of the common good and life in common, can society be healed, as well as the self, of the pride of being the centre of the world. Thus St Theodore, with fine introspection, helped his monks and ultimately also helps us to understand true life, to resist the temptation to set up our own will as the supreme rule of life and to preserve our true personal identity which is always an identity shared with others and peace of heart.

For Theodore the Studite an important virtue on a par with obedience and humility is philergia, that is, the love of work, in which he sees a criterion by which to judge the quality of personal devotion: the person who is fervent and works hard in material concerns, he argues, will be the same in those of the spirit. Therefore he does not permit the monk to dispense with work, including manual work, under the pretext of prayer and contemplation; for work to his mind and in the whole monastic tradition is actually a means of finding God. Theodore is not afraid to speak of work as the “sacrifice of the monk”, as his “liturgy”, even as a sort of Mass through which monastic life becomes angelic life. And it is precisely in this way that the world of work must be humanized and man, through work, becomes more himself and closer to God. One consequence of this unusual vision is worth remembering: precisely because it is the fruit of a form of “liturgy”, the riches obtained from common work must not serve for the monks’ comfort but must be earmarked for assistance to the poor. Here we can all understand the need for the proceeds of work to be a good for all. Obviously the “Studites’” work was not only manual: they had great importance in the religious and cultural development of the Byzantine civilization as calligraphers, painters, poets, educators of youth, school teachers and librarians.

Although he exercised external activities on a truly vast scale, Theodore did not let himself be distracted from what he considered closely relevant to his role as superior: being the spiritual father of his monks. He knew what a crucial influence both his good mother and his holy uncle Plato whom he described with the significant title “father” had had on his life. Thus he himself provided spiritual direction for the monks. Every day, his biographer says, after evening prayer he would place himself in front of the iconostasis to listen to the confidences of all. He also gave spiritual advice to many people outside the monastery. The Spiritual Testament and the Letters highlight his open and affectionate character, and show that true spiritual friendships were born from his fatherhood both in the monastic context and outside it.

The Rule, known by the name of Hypotyposis, codified shortly after Theodore’s death, was adopted, with a few modifications, on Mount Athos when in 962 St Athanasius Anthonite founded the Great Laura there, and in the Kievan Rus’, when at the beginning of the second millennium St Theodosius introduced it into the Laura of the Grottos. Understood in its genuine meaning, the Rule has proven to be unusually up to date. Numerous trends today threaten the unity of the common faith and impel people towards a sort of dangerous spiritual individualism and spiritual pride. It is necessary to strive to defend and to increase the perfect unity of the Body of Christ, in which the peace of order and sincere personal relations in the Spirit can be harmoniously composed.

It may be useful to return at the end to some of the main elements of Theodore’s spiritual doctrine: love for the Lord incarnate and for his visibility in the Liturgy and in icons; fidelity to Baptism and the commitment to live in communion with the Body of Christ, also understood as the communion of Christians with each other; a spirit of poverty, moderation and renunciation; chastity, self-control, humility and obedience against the primacy of one’s own will that destroys the social fabric and the peace of souls; love for physical and spiritual work; spiritual love born from the purification of one’s own conscience, one’s own soul, one’s own life. Let us seek to comply with these teachings that really do show us the path of true life.