My friend Benedictine Father Meinrad Miller told me about this essay, “The Vocation To Life” published in a recent issue of Homiletic and Pastoral Review by Father Charles Klamut. I was “blown away by it” and offer it to you here. It is truly an excellent essay; it captures the heart of what it means to be a Christian –a follower of Christ and His Church– and to be a true man or woman with a humanity. Recently, I’ve had this discussion with a dear friend about vocation and he can’t seem to get it across his mind (and heart) that there are things we need as a human being before being a monk or a priest. Father Charles gets it; Scola gets it as does Albacete and Benedict XVI and before him Paul VI and John Paul II. Are we listening carefully to the Master. On this feast of Saint Benedict, I offer this essay for us to reflect on.

Like the apostles, I first said “yes” to Christ because of the total answer he provided for my human need, and only within this context did a specific vocation to serve as a priest gradually begin to reveal itself.

A few years ago, during a retreat for priests, Msgr. Lorenzo Albacete shared with us a story of his friend, Cardinal Angelo Scola. When asked by a journalist about the shortage of vocations to the priesthood in Italy, Scola replied that the problem stemmed from a deeper crisis: the problem, he said, was that life itself is no longer seen as a vocation.

Albacete reflected on this insight for the next few days, calling it very important, explaining to us what he thought Scola was getting at. The call to life is something given, something prior to our thoughts and schemes. It’s even prior to the particular vocations like marriage and the priesthood. We did not choose it; it’s just there. Within the human heart is a cry for life, real life, eternal life: life properly so-called. The New Testament, using a more nuanced Greek vocabulary than our modern-day English, used multiple words for “life:” bios to refer to material, physical life; zoe to refer to a more comprehensive, metaphysical, all-encompassing life, such as the kind promised by Jesus. The heart cries for infinite life, not just bios, but zoe. The heart cries for a freedom and happiness which, alas, we cannot give ourselves. In short, the heart cries for God.

This call to life which our heart always hears, even if we don’t (affected as we are by reductionist cultural forces), is awakened and answered by the exceptional presence of Christ. Jesus Christ is the infinite made visible and historical, the answer to the heart’s cry for life: “I came that they might have life, and have it more abundantly” (John 10:10).

Albacete spoke of the experience of the first apostles as recorded in the Scriptures. For them, Christ provoked a total human awakening, provided a total human answer, not just a spiritual one. From Christ’s first question to John and Andrew, “What do you seek?” he was engaging them on the level of life itself. Their response to his question was: “Where are you staying?” This suggests their longing for a lasting place to be with him, to share life with him. Only with time would the call of Christ reveal itself in its ecclesiastical specifics, as a logical extension of the vocation to life.

A number of priests at the retreat were puzzled that so much time was spent on the general theme of the call to life, and they were wondering when the specifics of the priesthood, such as the Eucharist, would be addressed. Albacete insisted that the vocation to life, and subsequently, to Christianity, provided the solid foundation on which the vocation to the priesthood is built. Without the former, the latter will be unstable and will eventually crumble, as we have all sadly seen so many times in recent years.

The retreat had a major impact on me and on many of the others present. It challenged me to think more deeply about my entire life, not just my priesthood. I was challenged to recall why I was moved to be a Christian in the first place, let alone a priest. Looking at experiences along my way, I remembered how Christ really has, time and again, answered the cry of my heart. In unexpected and exceptional ways, Christ has made it possible for me to live a free and human life, and has rescued me from confusion and despair, from the prison of my ego. In this context, the specifics of the priesthood make sense. Like the apostles, I first said “yes” to Christ because of the total answer he provided for my human need, and only within this context did a specific vocation to serve as a priest gradually begin to reveal itself.

With the vocation to life as a defining principle, I began with excitement to notice a similar emphasis in Church teaching. Consider the line from the Second Vatican Council, often quoted by Pope John Paul II: “Christ, the new Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and his love, fully reveals man to himself and makes his supreme calling clear.”

Man is no longer a mystery, a stranger to himself. Humanity now knows who he/she is and who God is, thanks to Christ. Humanity now sees that life has meaning, that each of us has a “supreme calling.”

Pope Benedict XVI has advanced this theme in his own way, speaking repeatedly of the need for the Church to advance “a true humanism, which acknowledges that man is made in the image of God and wants to help him live in a way consonant with that dignity” (God is Love, 30). True humanism comes from Christ, because only Christ reveals man to himself, clarifying his supreme calling to life. The Pope, like his predecessor, seems unwilling to consign salvation to heaven. Rather, he seems eager to see the Kingdom arrive here and now, through the response of men and women to Christ’s call to life, bearing fruit in a true humanism of dignity and redemption.

Christians are the true humanists. Perhaps it’s time to be bolder in asserting this. Turning to the Pope’s most recent encyclical, Charity in Truth, the vocation to life is discussed with great insight in the context of the development of peoples. In an extended section discussing Pope Paul VI’s social teaching from forty years earlier, Pope Benedict reaffirms that progress and development cannot be reduced to the material plane, as, unfortunately, so often happens. Development involves not just having more, but being more, including the “whole man.”

Pope Paul VI, says Pope Benedict, insisted on the link between the proclamation of Christ and the advancement of the individual in society (the humanism theme again). Christ knows that man does not live on bread alone. Christ feeds man’s whole being with the Word of God, redeeming him, “developing” him, and thus enabling him, in turn, to contribute to the true development of others. Pope Paul VI insisted that progress is, first and foremost, a vocation, a call initiated and made possible by God, saying that “in the design of God, every man is called upon to develop and fulfill himself, for every life is itself a vocation.”

Continuing his discussion of Pope Paul VI and development, Pope Benedict says:

To regard development as a vocation is to recognize, on the one hand, that it derives from a transcendent call, and on the other hand that it is incapable, on its own, of supplying its ultimate meaning. Not without reason, the word “vocation” is also found in another passage of the Encyclical (by Pope Paul VI), where we read: “There is no true humanism but that which is open to the Absolute, and is conscious of a vocation which gives human life its true meaning” (Charity in Truth, 16).

It’s interesting that the word “vocation” is repeatedly mentioned (dozens of times), yet it’s not linked here to specific vocations to marriage or priesthood, as is typical in Catholic discussions. Instead, the word is used in an all-encompassing way: “being more,” “true humanism,” being called by God “to develop and fulfill himself.” This is a surprisingly historical and human approach, and seems a far cry from the “pie in the sky when you die,” otherworldly type of salvation for which Marx so bitterly criticized Christianity. The repeated references to “meaning” suggest the Pope’s deep awareness of the existential crisis that so many people face in recent times. This crisis saps the human spirit and thwarts development perhaps even more than material imbalances. The Pope wishes to see every human being respond to the vocation to development and thus flourish; he wishes to see the development of the “whole man” and “every man.” Who else in the world truly wants this?

When you experience something freeing and beautiful, love impels you to share it. The approach I have mentioned thus far, from all I have seen, heard, and read, is something truly original and exceptional. It has caused a paradigm shift in my own thinking, and an awareness of what it means to be a human, a Christian, and a priest. This shift is of seismic proportions, providing clarity to my mission and a new zest for life. It has made me feel more challenged and eager than ever, giving me a new way of looking at the future of the Church, to which I have pledged my life.

My human needs always precede my priesthood. When I am struggling as a priest, it is a sign that I am struggling as a man. The way Christ relates to me, looks at me, and saves me touches, on some deep, mysterious level, the recesses of my human heart. Deeper than my ecclesiastical vocation, he always reaches me at this human level, which, in turn, touches on my priesthood. He reaches out to me primarily through his Church, most specifically through my friends. As a friend recently said, “Treat friendship like the eighth sacrament—there you will understand the Church as the universal sacrament of salvation.”

The idea of life itself as a vocation puts the responsibility on each one of us to take this call seriously, and follow it, living out its implications in all their ensuing adventure. It charges Christianity with a new energy and new focus. It takes the emphasis off circumstances, putting it back onto my own reason and freedom, challenging me to seek out and follow what most moves me. It takes Christian life out of the confines of the sanctuary or church building and makes every detail of life significant and charged with meaning. It provides a context within which more specific vocations take on perspective and focus.

In my experience as a priest, people are more confused and more desperate than ever to find meaning in life. Unfortunately, many see their Christian faith as something to get them to heaven (hopefully) when they die, so long as they are “good.” They do not see how faith makes their real life–here and now–better and happier, new and beautiful. Some, especially the young, may speak earnestly about finding their “vocation.” But this is usually muddled and often means no more than finding a “soul mate” to make them happy, as the popular myth proposes, collapsing the vocation to life into the vocation to marriage, priesthood, etc. Those concerned with “development” often zealously work for social justice, but fail to see how the care of people’s material needs connects to the needs of their heart. They end up offering, in spite of their good intentions, far too little. Often priests seem to allow their self-awareness to be reduced to religious specialization. These are fragmented people seeking fragmented goals.

In the midst of this turmoil and confusion, Cardinal Scola, Msgr. Albacete, and the recent popes insist that life is a “vocation.” This cuts to the core and returns us to the beginning, the first things that matter: the cry of the human heart for God. Fr. Luigi Giussani once said, “The true protagonist of history is the beggar, Christ, who begs for man’s heart; and man’s heart, which begs for Christ.” If ever there was a need for a new bunch of protagonists in the Church and in the world, it is now.

Today, Christian faith is often reduced to sentimentality or sectarianism, or a subjectively comforting ideology. The idea of faith as knowledge of real, existing (if mysterious) things seems more and more foreign. The connection of faith to reality and life seems farther than ever. The irrelevance of faith to life seems more obvious than ever. The casualties are people, and by extension, church, culture, and society.

“Life itself is no longer seen as a vocation,” said Cardinal Scola to the journalist. “This is the real problem.”

What if the Church is right? What if there really is a vocation to life, a call from God to have life, and have it more abundantly, each and every day? What if this vocation is really a call to an integral development, beginning with self and extending to “every man”? What if it is a call for the fulfillment of the “whole man”; a call not just to have more, but to be more? What if it is a call to a “true humanism”? How might this change the way we live as Christians? It would seem, at the very least, to require a serious, ongoing response, engaging all our intelligence and freedom. Imagine what the Church, and the world, might look like if a sizeable number, or even a handful, of people were behaving this way.

Well, it may mean that the cry of my heart for life is not absurd; that it is not to be suppressed, censored, or reduced to despair and resignation; nor should it be too painful to bear. It may mean, instead, that the cry of my heart is beautiful, lovingly made and given by God–and answered. It may point out that the meaning of my life is to answer the call that life itself makes. It may mean that the infinite really has revealed itself in the person of Jesus, who really died and rose. It may mean that a whole new horizon of possibility has opened.

Suddenly, being a Christian just became a lot more exciting.

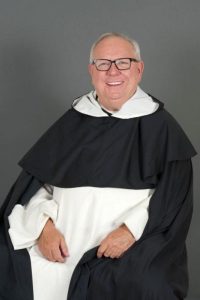

The author

Fr. Charles Klamut was ordained in 1999 for the Diocese of Peoria, Illinois. He has served in parish and high school ministry. He is currently working in campus ministry at St John’s Catholic Newman Center at the University of Illinois.