From Salvifici Doloris – On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering (1984), by Pope Saint John Paul II

From Salvifici Doloris – On the Christian Meaning of Human Suffering (1984), by Pope Saint John Paul II

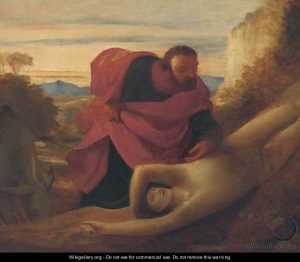

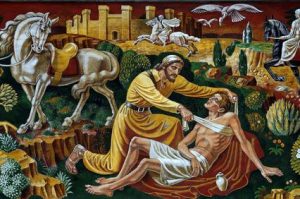

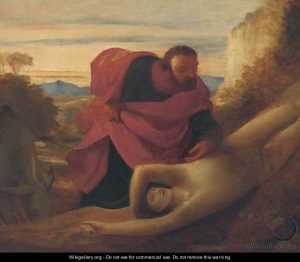

THE GOOD SAMARITAN

28. To the Gospel of suffering there also belongs—and in an organic way—the parable of the Good Samaritan. Through this parable Christ wished to give an answer to the question: “Who is my neighbour?”(90) For of the three travellers along the road from Jerusalem to Jericho, on which there lay half-dead a man who had been stripped and beaten by robbers, it was precisely the Samaritan who showed himself to be the real “neighbour” of the victim: “neighbour” means also the person who carried out the commandment of love of neighbour. Two other men were passing along the same road; one was a priest and the other a Levite, but each of them ” saw him and passed by on the other side”. The Samaritan, on the other hand, “saw him and had compassion on him. He went to him, … and bound up his wounds “, then “brought him to an inn, and took care of him”(91). And when he left, he solicitously entrusted the suffering man to the care of the innkeeper, promising to meet any expenses.

The parable of the Good Samaritan belongs to the Gospel of suffering. For it indicates what the relationship of each of us must be towards our suffering neighbour. We are not allowed to “pass by on the other side” indifferently; we must “stop” beside him. Everyone who stops beside the suffering of another person, whatever form it may take, is a Good Samaritan. This stopping does not mean curiosity but availability. It is like the opening of a certain interior disposition of the heart, which also has an emotional expression of its own. The name “Good Samaritan” fits every individual who is sensitive to the sufferings of others, who “is moved” by the misfortune of another. If Christ, who knows the interior of man, emphasizes this compassion, this means that it is important for our whole attitude to others’ suffering. Therefore one must cultivate this sensitivity of heart, which bears witness to compassion towards a suffering person. Some times this compassion remains the only or principal expression of our love for and solidarity with the sufferer.

Nevertheless, the Good Samaritan of Christ’s parable does not stop at sympathy and compassion alone. They become for him an incentive to actions aimed at bringing help to the injured man. In a word, then, a Good Samaritan is one who brings help in suffering, whatever its nature may be. Help which is, as far as possible, effective. He puts his whole heart into it, nor does he spare material means. We can say that he gives himself, his very “I”, opening this “I” to the other person. Here we touch upon one of the key-points of all Christian anthropology. Man cannot “fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself”(92). A Good Samaritan is the person capable of exactly such a gift of self.

29. Following the parable of the Gospel, we could say that suffering, which is present under so many different forms in our human world, is also present in order to unleash love in the human person, that unselfish gift of one’s “I” on behalf of other people, especially those who suffer. The world of human suffering unceasingly calls for, so to speak, another world: the world of human love; and in a certain sense man owes to suffering that unselfish love which stirs in his heart and actions. The person who is a ” neighbour” cannot indifferently pass by the suffering of another: this in the name of fundamental human solidarity, still more in the name of love of neighbour. He must “stop”, “sympathize”, just like the Samaritan of the Gospel parable. The parable in itself expresses a deeply Christian truth, but one that at the same time is very universally human. It is not without reason that, also in ordinary speech, any activity on behalf of the suffering and needy is called “Good Samaritan” work.

In the course of the centuries, this activity assumes organized institutional forms and constitutes a field of work in the respective professions. How much there is of “the Good Samaritan” in the profession of the doctor, or the nurse, or others similar! Considering its “evangelical” content, we are inclined to think here of a vocation rather than simply a profession. And the institutions which from generation to generation have performed ” Good Samaritan” service have developed and specialized even further in our times. This undoubtedly proves that people today pay ever greater and closer attention to the sufferings of their neighbour, seek to understand those sufferings and deal with them with ever greater skill. They also have an ever greater capacity and specialization in this area. In view of all this, we can say that the parable of the Samaritan of the Gospel has become one of the essential elements of moral culture and universally human civilization. And thinking of all those who by their knowledge and ability provide many kinds of service to their suffering neighbour, we cannot but offer them words of thanks and gratitude.

These words are directed to all those who exercise their own service to their suffering neighbour in an unselfish way, freely undertaking to provide “Good Samaritan” help, and devoting to this cause all the time and energy at their disposal outside their professional work. This kind of voluntary “Good Samaritan” or charitable activity can be called social work; it can also be called an apostolate, when it is undertaken for clearly evangelical motives, especially if this is in connection with the Church or another Christian Communion. Voluntary “Good Samaritan” work is carried out in appropriate milieux or through organizations created for this purpose. Working in this way has a great importance, especially if it involves undertaking larger tasks which require cooperation and the use of technical means. No less valuable is individual activity, especially by people who are better prepared for it in regard to the various kinds of human suffering which can only be alleviated in an individual or personal way. Finally, family help means both acts of love of neighbour done to members of the same family, and mutual help between families.

It is difficult to list here all the types and different circumstances of “Good Samaritan” work which exist in the Church and society. It must be recognized that they are very numerous, and one must express satisfaction at the fact that, thanks to them, the fundamental moral values, such as the value of human solidarity, the value of Christian love of neighbour, form the framework of social life and interhuman relationships and combat on this front the various forms of hatred, violence, cruelty, contempt for others, or simple “insensitivity”, in other words, indifference towards one’s neighbour and his sufferings.

Here we come to the enormous importance of having the right attitudes in education. The family, the school and other education institutions must, if only for humanitarian reasons, work perseveringly for the reawakening and refining of that sensitivity towards one’s neighbour and his suffering of which the figure of the Good Samaritan in the Gospel has become a symbol. Obviously the Church must do the same. She must even more profoundly make her own—as far as possible—the motivations which Christ placed in his parable and in the whole Gospel. The eloquence of the parable of the Good Samaritan, and of the whole Gospel, is especially this: every individual must feel as if called personally to bear witness to love in suffering. The institutions are very important and indispensable; nevertheless, no institution can by itself replace the human heart, human compassion, human love or human initiative, when it is a question of dealing with the sufferings of another. This refers to physical sufferings, but it is even more true when it is a question of the many kinds of moral suffering, and when it is primarily the soul that is suffering.

30. The parable of the Good Samaritan, which —as we have said—belongs to the Gospel of suffering, goes hand in hand with this Gospel through the history of the Church and Christianity, through the history of man and humanity. This parable witnesses to the fact that Christ’s revelation of the salvific meaning of suffering is in no way identified with an attitude of passivity. Completely the reverse is true. The Gospel is the negation of passivity in the face of suffering. Christ himself is especially active in this field. In this way he accomplishes the messianic programme of his mission, according to the words of the prophet: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord”(93). In a superabundant way Christ carries out this messianic programme of his mission: he goes about “doing good”(94). and the good of his works became especially evident in the face of human suffering. The parable of the Good Samaritan is in profound harmony with the conduct of Christ himself.

Finally, this parable, through its essential content, will enter into those disturbing words of the Final Judgment, noted by Matthew in his Gospel: “Come, O blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was in prison and you came to me”(95). To the just, who ask when they did all this to him, the Son of Man will respond: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me”(96). The opposite sentence will be imposed on those who have behaved differently: “As you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me”.”

One could certainly extend the list of the forms of suffering that have encountered human sensitivity, compassion and help, or that have failed to do so. The first and second parts of Christ’s words about the Final Judgment unambiguously show how essential it is, for the eternal life of every individual, to “stop”, as the Good Samaritan did, at the suffering of one’s neighbour, to have “compassion” for that suffering, and to give some help. In the messianic programme of Christ, which is at the same time the programme of the Kingdom of God, suffering is present in the world in order to release love, in order to give birth to works of love towards neighbour, in order to transform the whole of human civilization into a “civilization of love”. In this love the salvific meaning of suffering is completely accomplished and reaches its definitive dimension. Christ’s words about the Final Judgment enable us to understand this in all the simplicity and clarity of the Gospel.

These words about love, about actions of love, acts linked with human suffering, enable us once more to discover, at the basis of all human sufferings, the same redemptive suffering of Christ. Christ said: “You did it to me”. He himself is the one who in each individual experiences love; he himself is the one who receives help, when this is given to every suffering person without exception. He himself is present in this suffering person, since his salvific suffering has been opened once and for all to every human suffering. And all those who suffer have been called once and for all to become sharers “in Christ’s sufferings”(98), just as all have been called to “complete” with their own suffering “what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions”(99). At one and the same time Christ has taught man to do good by his suffering and to do good to those who suffer. In this double aspect he has completely revealed the meaning of suffering.

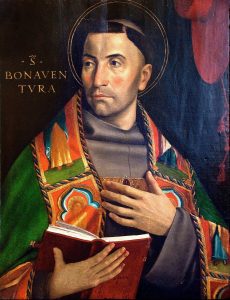

We are honoring the memory of St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio (ca. 1221-1274) today. One of the great scholastic theologians and pastors of the Church. I hope the Thomists won’t get mad!

We are honoring the memory of St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio (ca. 1221-1274) today. One of the great scholastic theologians and pastors of the Church. I hope the Thomists won’t get mad!