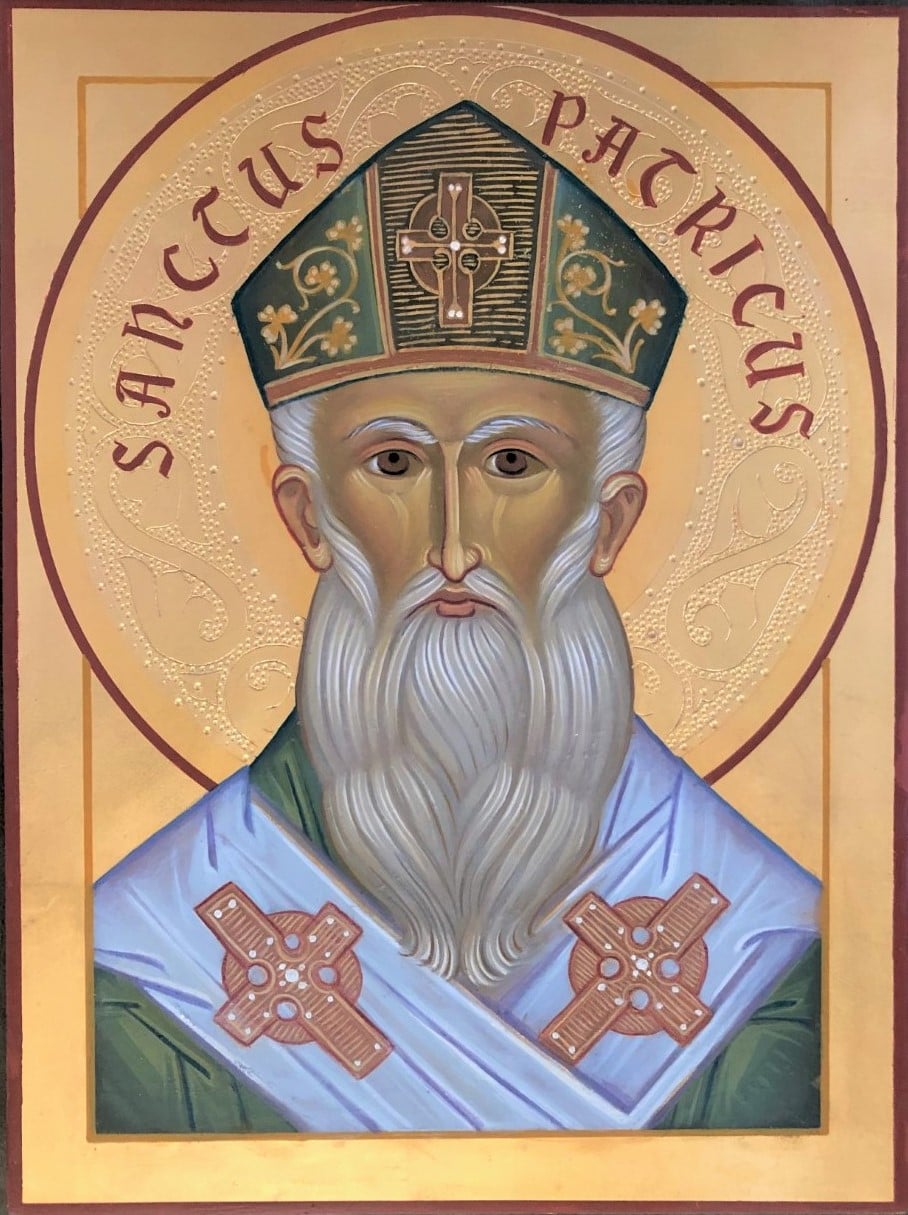

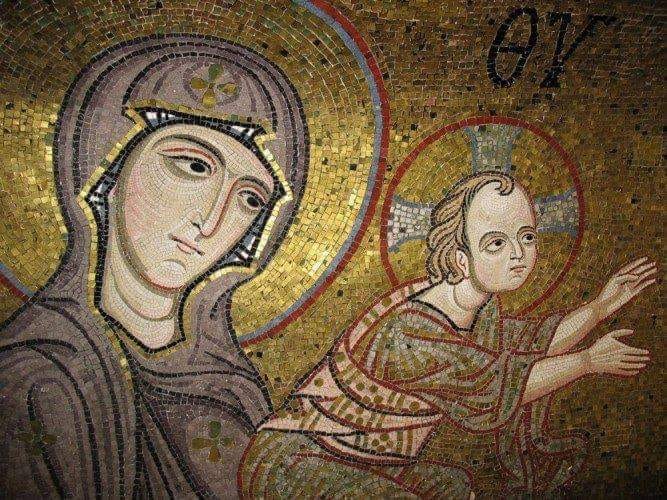

The Churches honor the great missionary bishop and preacher of Jesus Christ, Patrick. His famous Litany is noted below which is rich scope and detail reflecting a deep relationship with the Holy Trinity. Most Christians only acknowledge one member of the Trinity forgetting the perichoresis which exists. We Catholics and Orthodox, as a point of fact, always pray addressing God the Father, through the Son under the power of the Holy Spirit.

Blessed feast to my family (on the maternal side) and to the people of Ireland.

The Lorica

I arise today, through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity, through belief in the threeness, through confession of the oneness, of the Creator of Creation.

I arise today, through the strength of Christ’s birth with his baptism, through the strength of his crucifixion with his burial, through the strength of his resurrection with his ascension, through the strength of his descent for the judgment of Doom.

I arise today, through the strength of the love of the Cherubim, in obedience of angels, in the service of archangels, in the hope of the resurrection to meet with reward, in the prayers of patriarchs, in prediction of prophets, in preaching of apostles, in faith of confessors, in innocence of holy virgins, in deeds of righteous men.

I arise today, through the strength of heaven; light of sun, radiance of moon, splendor of fire, speed of lightning, swiftness of wind, depth of sea, stability of earth, firmness of rock.

I arise today, through God’s strength to pilot me: God’s might to uphold me, God’s wisdom to guide me, God’s eye to look before me, God’s ear to hear me, God’s word to speak to me, God’s hand to guard me, God’s way to lie before me, God’s shield to protect me, God’s host to save me, from the snares of devils, from temptations of vices, from every one who shall wish me ill, afar and anear, alone and in a multitude.

I summon today, all these powers between me and those evils, against every cruel merciless power that may oppose my body and soul, against incantations of false prophets, against black laws of pagandom, against false laws of heretics, against craft of idolatry, against spells of women and smiths and wizards, against every knowledge that corrupts man’s body and soul.

Christ to shield me today, against poisoning, against burning, against drowning, against wounding, so there come to me abundance of reward. Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ on my right, Christ on my left, Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down, Christ when I arise, Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me, Christ in the mouth of every one who speaks of me, Christ in the eye of every one that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

I arise today, through a mighty strength, the invocation of the Trinity, through belief in the threeness, through confession of the oneness, of the Creator of Creation. Salvation is of the Lord. Salvation is of the Lord. Salvation is of Christ. May Thy Salvation, O Lord be ever with us. Amen.

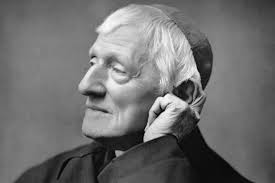

Icon: Marek Czarnecki, 2020