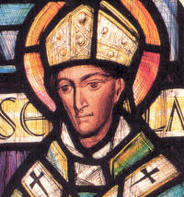

Saint Anselm is a towering figure in monastic, theological and philosophical circles whose works take diligence in getting your mind around. Even centuries later he speaks with precision. Saint Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109) an Italian by birth, Anselm held various academic and ecclesial titles; he was the archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 until his death in 1109. The Church tells us he is the father of scholasticism and famous for the ontological argument for God’s existence. Though never formally canonized –the process was not developed then– Anselm was acknowledged a saint by Clement XI and named a Doctor of the Church (1 of 33). One point I noticed recently about Saint Anselm and the promotion of truth is this…

Saint Anselm is a towering figure in monastic, theological and philosophical circles whose works take diligence in getting your mind around. Even centuries later he speaks with precision. Saint Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109) an Italian by birth, Anselm held various academic and ecclesial titles; he was the archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 until his death in 1109. The Church tells us he is the father of scholasticism and famous for the ontological argument for God’s existence. Though never formally canonized –the process was not developed then– Anselm was acknowledged a saint by Clement XI and named a Doctor of the Church (1 of 33). One point I noticed recently about Saint Anselm and the promotion of truth is this…

Category: Year of Saint Anselm

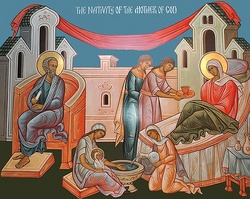

Saint Anselm’s prayer for the Birth of Our Lady

In Honor of Our Lady’s Nativity

that I may praise thee, O sacred Virgin; give me strength against thine

enemies, and against the enemy of the whole human race. Give me strength humbly

to pray to thee. Give me strength to praise thee in prayer with all my powers,

through the merits of thy most sacred nativity, which for the entire Christian

world was a birth of joy, the hope and solace of its life.

O most holy Virgin, then was the world made light. Happy is thy stock, holy thy

root, and blessed thy fruit, for thou alone as a virgin, filled with the Holy

Spirit, didst merit to conceive thy God, as a virgin to bear Thy God, as a

virgin to bring Him forth, and after His birth to remain a virgin.

therefore upon me a sinner, and give me aid, O Lady, so that just as thy

nativity, glorious from the seed of Abraham, sprung from the tribe of Juda,

illustrious from the stock of David, didst announce joy to the entire world, so

may it fill me with true joy and cleanse me from every sin.

Virgin most prudent, that the gladsome joys of thy most helpful nativity may

put a cloak over all my sins. O holy Mother of God, flowering as the lily, pray

to thy sweet Son for me, a wretched sinner. Amen.

Saint Anselm on the Honor of God

Whoever does not pay to God his honor due Him dishonors Him and removes from Him what belongs to Him; and this removal, or dishonoring, constitutes a sin. However as long as he does not repay what he has stolen, he remains guilty.

Saint Anselm on the Divine Will

For these three persons do not have will or power according to their relationships but rather according to the fact that each single person is God.

Power of freedom

…[freedom] is so powerful that as long as a man wills to use it nothing is able to remove from him the … uprightness (i.e., justice) which he has. By contrast, justice is not a natural possession.

Anselm’s view of sin

Suppose you were to find yourself in the presence of God and

someone were to give you the command: “Look in that direction.” And suppose

that, on the contrary, God were to say: “I am absolutely unwilling for you to

look.” Ask yourself in your heart what there is, among all existing things, for

the sake of which you ought to take that look in violation of God’s will.

Saint Anselm of Canterbury, Cur Deus Homo

What does justice/rectitude require?

Justice/rectitude requires reason because “… a nature which does not know rightness is not able to will it.”

The honor of God

Uprightness is the sole and complete honor which we owe to God and which God demands from us.

Saint Anselm sought to raise the mind to the contemplation of God, Pope reminds

Pope Benedict

XVI wrote to Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, retired archbishop of Bologna, on the

occasion of the ninth centenary of the death of Saint Anselm. I find this letter

to be an amazing testimony to the operative graces at work in the Church 900

years ago and today.

What is said by the Holy Father is a great reminder of what our aim ought to be

as faithful Christians, and for those called to ministry, what our

responsibilities are.

In view of the

celebrations in which you, venerable brother, will take part as my legate in

the illustrious city of Aosta in honor of the ninth centenary of the death of

St. Anselm, which took place in Canterbury on 21 April 1109, I would like to

give you a special message in which I wish recall the main features of this

great monk, theologian and pastor of souls, whose work has left a deep mark on

the history of the Church.

The anniversary

is indeed an opportunity not to be missed to renew the memory of one of the

brightest figures in the tradition of the Church and in the history of Western

European thought. The exemplary monastic experience of Anselm, his

original method of rethinking the Christian mystery, his subtle philosophical

and theological doctrine, his teaching on the inviolable value of conscience

and on freedom as the responsible adherence to truth and goodness, his

passionate work as a shepherd of souls, dedicated with all his strength to the

promotion of “freedom of the Church,” have never ceased to arouse in

the past the deepest interest, which the memory of his death is happily

reigniting and encouraging in many ways and in different places.

In this memorial

of the “Magnificent Doctor” — as St. Anselm is called — the Church

of Aosta cannot but be recognized, the Church in which he was born and which is

rightly pleased to consider Anselm as her most illustrious son. Even when he

left Aosta in the time of his youth, he continued to carry in his memory and in

his heart the bundle of memories that was never far from his thoughts in the

most important moments of life. Among those memories, a particular place was

certainly reserved for the sweet image of his mother and the majestic mountains of his

valley with their high peaks, and perennial snow, in which he saw represented,

as if in a fascinating and suggestive symbol, the sublimity of God. To

Anselm – “a child raised in the mountains,” as Admero his biographer

calls him, (Vita Sancti Anselmi,

i, 2) – God appears to be that of which you cannot think of something bigger

[the translator probably meant “greater”]: perhaps his intuition was not

unrelated to the childhood view of those inaccessible peaks. Already as a child

he thought that in order to find God it was necessary to “climb to the

summit of the mountain” (ibid.). In fact, he will realize more and more

that God remains at an inaccessible height, located beyond the horizons

which man is able to reach,

since God is beyond the thinkable. Because of this, the journey in search of

God, at least on this earth, will never end, but will always be thought and

desire, the rigorous process of the intellect and the imploring inquiry of the

heart.

The intense

desire to know and the innate propensity for clarity and logical rigor will

push Anselm towards the “scholeae” [schools] of his time. He will

therefore join the monastery of Le Bec, where his inclination for dialectic

reflection will be satisfied and above all, where his cloistered vocation will

enkindle. To dwell on the years of the monastic life of Anselm is to encounter

a faithful religious, “constantly occupied in God alone and in the

disciplines of heaven” — as his biographer writes — in order to achieve

“such a summit of divine speculation that would enable him by a path

opened by God to penetrate, and, once penetrated, to explain the most obscure

and previously unresolved questions concerning the divinity of God and our

faith and to prove with clear reasons that what he stated belonged to

sure Catholic doctrine” (Vita Sancti Anselmi, i, 7). With these words, his biographer

describes the theological method of St. Anselm, whose thought was ignited

and illuminated in prayer. It is he himself that confesses, in his famous

work, that the understanding of faith is an approach toward a vision, which we

all yearn for and which we all hope to enjoy at the end of our earthly pilgrimage,

“Quoniam inter fidem et speciem intellectum quem in hac vita capimus esse

medium intelligo: quanto aliquis ad illum proficit, tanto eum propinquare

speciei, ad quam omnes anhelamus, existimo (Cur Deus homo, Commendatio).

The saint

desired to achieve the vision of the logical relationships inherent to

the mystery, to perceive the “clarity of truth,” and thus to

grasp the evidence of the “necessary reasons,” intimately bound

to the mystery. A bold plan certainly, and it is one whose success still occupies

the reflections of the students of Anselm today. In fact, his search of the

“intellectus” [intellect] positioned between “fides”

[faith] and “species” [vision] comes out of the source of the same

faith and is sustained by confidence in reason, through which faith in a

certain way is illuminated. The intent of Anselm is clear: “to raise the mind to

contemplation of God”

(Proslogion,

Proemium). There remain, in any event, for every theological research, his

programmatic words: “I do not try, Lord, to penetrate your depth, because

I cannot, even from a distance, compare it with my intellect, but I want to

understand, at least up to a certain point, your truth, which my heart believes

and loves. I do not seek, in fact, to try to understand it in order to believe

it, but I believe in order to understand it.”[Non quaero intelligere ut

credam, sed credo ut intelligam] (Proslogion, 1).

In Anselm, prior

and abbot of Le Bec, we underline some characteristics that further define his

personal profile. What strikes us, first of all, is his charism as an expert

teacher of spiritual life,

one who knows and wisely illustrates the ways of monastic perfection. At the

same time, one is fascinated by his instructive geniality, which is expressed

in that discernment method

— which he names, the “via discretionis” (Ep. 61) — which is a

small image of his whole life, an image composed of both mercy and firmness.

The peculiar ability which he demonstrates in initiating disciples to the

experience of authentic prayer is very peculiar: in particular, his

“Orationes sive Meditationes,” eagerly requested and widely used,

which have contributed to making many people of his time “anime

oranti” [praying souls], as with his other works, have proved themselves a

valuable catalyst in making the Middle Ages a “thinking” and, we

might add, “conscientious” period. One would say that the most

authentic Anselm can be found at Le Bec, where he remained thirty three years,

and where he was much loved. Thanks to the maturity that he acquired in a

similar environment of reflection and prayer, he will be able, as well in the

midst of the subsequent trials as bishop, to declare: “I will not retain

in my heart any resentment for any one” (Ep. 321).

The nostalgia

of the monastery will

accompany him for the rest of his life. He confessed it himself when he was

constrained, to his deepest sorrow and that of his monks, to leave the

monastery to assume the Episcopal ministry to which did not feel well disposed:

“It is well known to many,” he wrote to Pope Urban II, “the

violence which was done to me, and how much I was reluctant and contrary, when

I was brought as a bishop to England and how I explained the reasons of nature,

age, weakness and ignorance, which were opposed to this office and that absolutely

detest and shun scholastic duties, which I cannot dedicate myself to at all

without endangering the salvation of my soul” (Ep. 206). He confides later

with his monks in these terms: “I have lived for 33 years a monk —

three years without responsibility, 15 as prior, and as many as abbot — in

such a way that all the good people that knew me loved me, certainly not by my

own merits but for the grace of God, and the ones that loved me most

were those that knew me most intimately and with greatest familiarity” (Ep. 156). And he added: “You

have been many to come to Le Bec … Many of you I surrounded with a love

so tender and sweet

that each one had the impression that I did not love anyone else in the same

way” (ibid.).

Appointed

Archbishop of Canterbury and beginning, in this way, his most troubled journey,

his “love of truth” (Ep. 327), his uprightness, his strict loyalty to

conscience, his “Episcopal freedom” (Ep. 206), his ” Episcopal

honesty” (Ep. 314), his tireless work for the liberation of the Church

from the temporal conditionings and from the servitude of calculations that are

incompatible with his spiritual nature will appear in their full light. His

words to King Henry remain exemplary in this respect, “I reply that in

neither baptism nor in any other ordination that I have received, did I

promised to observe the law or the custom of your father or of the Archbishop

Lanfranco, but the law of God and of all the orders received” (Ep. 319).

For Anselm, the primate of the Church of England, one principle

applies: “I

am a Christian, I am a monk, I am a Bishop: I desire to be faithful to all,

according to the debt I have with each”

(Ep. 314). In this vein he does not hesitate to say: “I prefer to be in

disagreement with men than, agreeing with them, to be in disagreement with God” (Ep. 314). Precisely for this

reason he feels ready even for the supreme sacrifice: “I am not afraid to

shed my blood, I fear no wound in my body nor the loss of any material

good” (Ep. 311).

It is

understandable that, for all these reasons, Anselm still retains a great

actuality and a strong appeal, in as much as it is fruitful to revisit and

republish his writings, and together meditate continuously on his life. For

this reason I have rejoiced that Aosta, on the occasion of the ninth centenary

of the death of the saint, has distinguished itself with a set of appropriate

and intelligent initiatives — especially with the careful edition of his works

— with the intention to make known and loved the teachings and examples of this,

its illustrious son. I entrust to you, Venerable Brother, the task of bringing

to the faithful of the ancient and beloved city of Aosta the exhortation to

remember with admiration and affection this great fellow citizen of theirs,

whose light continues to shine throughout the Church, especially where the love

for the truths of faith and the desire for their study by the light of reason

are cultivated. And, in fact, faith and reason — “fides et ratio” — are united admirably in

Anselm. I send, with these heartfelt sentiments through you, venerable

brother, to the Bishop, Monsignor Giuseppe Anfossi, the clergy, the religious

and the faithful of Aosta and to all those who take part in the celebrations in

honor of the “Magnificent Doctor,” a special apostolic blessing,

propitiatory of an abundant outpouring of heavenly favors.

Saint Anselm: a wise, faithful, magnanimous servant of the Lord

Lo, a brave bishop, lo, a monk most faithful,

Crowned with laurel, flourisheth as a Doctor:

Crowned with laurel, flourisheth as a Doctor:

Now let our chorus vie in joyful anthems,

Singing to Anselm.

Filllled with wisdom, ere he grew to manhood,

Earth’s fleeting beauty prudently he feared:

Then, through the leading of his master, Lanfranc,

Entered the cloister.

High to the secret of the Word he soared,

Borne in the pinions of a faith unshaken,

Who from the purest fountainheads of doctrine

Draweth more deeply?

Thou, tender Father, chosen to be Abbot,

Wast to thy children lovingly devoted,

Bearing the feeble on thy friendly shoulders,

Spurring the zealous.

Lo, the king calls thee to the seat of honor: Why fear the conflict? Triumph comes quickly; Far-distant nations soon with light thou fillest, O noble exile.

Liberty holy for the flock redeemed,

Liberty, which Christ places over all things,

Impelleth Anselm: who could be more zealous

As its defender?

Thee, Rome acclaimeth, glorious Archbishop.

Thee the high Pontiff giveth worthy honours;

Silent the Fathers; of thee the faith demandeth:

Guard thou its doctrine.

Think on thy chosen flock, and be their patron:

Pray the eternal Trinity to bless them,

His be the praises through the world resounding

Now and forever. Amen.

Hymn at Vigils for the feast of Saint Anselm of Canterbury (and Bec)