If you are in the greater New Haven, Connecticut area this coming weekend, “In Charge of the Fire” is well worth the effort to see. The writer, actors and director capture the essence of the life of Saint Paul and it reminds us of the salient points of this saint’s life and work for Christ. I think this a wonderful contribution to the celebrations happening in the Year of Saint Paul.

Category: Saint Paul

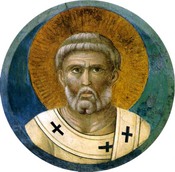

Pope Benedict’s homily for the Conversion of Saint Paul

It is a great joy every time we find ourselves gathered at the tomb of the Apostle Paul on the liturgical feast of his conversion to conclude the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. I greet all of you with affection. I greet in a special way Cardinal Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo, the abbot [Edmund Powers] and the community of monks who are hosting us. I also greet Cardinal Kasper, the president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I greet along with him the lord cardinals who are present, the bishops and the pastors of the various Churches and ecclesial communities gathered here this evening.

It is a great joy every time we find ourselves gathered at the tomb of the Apostle Paul on the liturgical feast of his conversion to conclude the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. I greet all of you with affection. I greet in a special way Cardinal Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo, the abbot [Edmund Powers] and the community of monks who are hosting us. I also greet Cardinal Kasper, the president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I greet along with him the lord cardinals who are present, the bishops and the pastors of the various Churches and ecclesial communities gathered here this evening.

A special word of recognition goes to those who worked together in preparing the prayer guides, experiencing firsthand the exercise of reflecting and meeting in listening to each other and, all together, to the Word of God.

St. Paul’s conversion offers us a model that shows us the way to full unity. Unity in fact requires a conversion: from division to communion, from broken unity to healed and full unity. This conversion is the gift of the Risen Christ, as it was for St. Paul. We heard this from the Apostle himself in the reading proclaimed just a moment ago: “By the grace of God I am what I am” (1 Corinthians 15:10).

The same Lord, who called Saul on the road to Damascus, addresses himself to the members of the Church — which is one and holy — and calling each by name asks: Why have you divided me? Why have you wounded the unity of my body?

Conversion implies two dimensions. In the first step we recognize our faults in the light of Christ, and this recognition becomes sorrow and repentance, desire for a new beginning. In the second step we recognize that this new road cannot come from us. It consists in letting ourselves be conquered by Christ. As St. Paul says: “I continue my pursuit in hope that I may possess it, since I have indeed been conquered by Christ Jesus” (Philippians 3:12).

Conversion demands our yes, my “pursuit”; it is not ultimately my activity, but a gift, a letting

ourselves be formed by Christ; it is death and resurrection. This is why St. Paul does not say: “I converted” but rather “I died” (Galatians 2:19), I am a new creature. In reality, St. Paul’s conversion was not a passage from immorality to morality, from a mistaken faith to a right faith, but it was a being conquered by Christ: the renunciation of his own perfection; it was the humility of one who puts himself without reserve in the service of Christ for the brethren. And only in this renunciation of ourselves, in this conforming to Christ are we also united among ourselves; we become “one” in Christ. It is communion with the risen Christ that gives us unity.

ourselves be formed by Christ; it is death and resurrection. This is why St. Paul does not say: “I converted” but rather “I died” (Galatians 2:19), I am a new creature. In reality, St. Paul’s conversion was not a passage from immorality to morality, from a mistaken faith to a right faith, but it was a being conquered by Christ: the renunciation of his own perfection; it was the humility of one who puts himself without reserve in the service of Christ for the brethren. And only in this renunciation of ourselves, in this conforming to Christ are we also united among ourselves; we become “one” in Christ. It is communion with the risen Christ that gives us unity.

We can observe an interesting analogy with the dynamic of St. Paul’s conversion also in meditating on the biblical text of the prophet Ezekiel (37:15-28), which was chosen as a basis for our prayer this year. In it, in fact, the symbolic gesture is presented of two sticks being joined into one in the prophet’s hand, who represents God’s future action with this gesture. It is the second part of Chapter 37, which in the first part contains the celebrated vision of the dry bones and the resurrection of Israel, worked by the Spirit of God.

How can we not see that the prophetic sign of the reunification of the people of Israel is placed after the great symbol of the dry bones brought to life by the Spirit? There follows from this a theological pattern analogous to that of St. Paul’s conversion: God’s power is first and he works the resurrection as a new creation by his Spirit. This God, who is the Creator and is able to resurrect the dead, is also able to bring a people divided in two back to unity.

Paul — like Ezekiel but more than Ezekiel — becomes the chosen instrument of the preaching of the unity won by Christ through his cross and resurrection: the unity between the Jews and the pagans, to form one new people. Christ’s resurrection extends the boundary of unity: not only the unity of the tribes of Israel, but the unity of the Jews and the pagans (cf. Ephesians 2; John 10:16); the unification of humanity dispersed by sin and still more the unity of all who believe in Christ.

Paul — like Ezekiel but more than Ezekiel — becomes the chosen instrument of the preaching of the unity won by Christ through his cross and resurrection: the unity between the Jews and the pagans, to form one new people. Christ’s resurrection extends the boundary of unity: not only the unity of the tribes of Israel, but the unity of the Jews and the pagans (cf. Ephesians 2; John 10:16); the unification of humanity dispersed by sin and still more the unity of all who believe in Christ.

We owe this choice of the passage from the prophet Ezekiel to our Korean brothers, who felt the call of this biblical passage strongly, both as Koreans and Christians. In the division of the Jewish people into two kingdoms they saw themselves reflected, the children of one land who, on account of political events, have been divided, north from south. Their human experience helped them to better understand the drama of the division among Christians.

Now, from this Word of God, chosen by our Korean brothers and proposed to all, a truth full of hope emerges: God allows his people a new unity, which must be a sign and an instrument of reconciliation and peace, even at the historical level, for all nations. The unity that God gives his Church, and for which we pray, is naturally communion in the spiritual sense, in faith and in charity; but we know that this unity in Christ is also the ferment of fraternity in the social sphere, in relations between nations and for the whole human family. It is the leaven of the Kingdom of God that makes all the dough rise (cf. Matthew 13:33).

In this sense, the prayer that we offer up in these days, taking our cue from the prophecy of Ezekiel, has also become intercession for the different situations of conflict that afflict humanity at present. There where human words become powerless, because the tragic noise of violence and arms prevails, the prophetic power of the Word of God does not weaken and it repeats to us that peace is possible, and that we must be instruments of reconciliation and peace. For this reason our prayer for unity and peace always requires confirmation by courageous gestures of reconciliation among us Christians.

Once again I think of the Holy Land: how important it is that the faithful who live there, and the pilgrims who travel there, offer a witness to everyone that diversity of rites and traditions need not be an obstacle to mutual respect and to fraternal charity. In the legitimate diversity of different positions we must seek unity in faith, in our fundamental “yes” to Christ and to his one Church. And thus the differences will no longer be an obstacle that separates but richness in the multiplicity of the expressions of a common faith.

I would like to conclude this reflection of mine with a reference to an event that we older people here have certainly not forgotten. In this place on Jan. 25, 1959, exactly 50 years ago, Blessed Pope John XXIII announced for this first time his desire to convoke “an ecumenical Council for the universal Church” (AAS LI [1959], p. 68). He made this announcement to the cardinals in the chapter room of the Monastery of St. Paul, after having celebrated solemn Mass in the Basilica.

I would like to conclude this reflection of mine with a reference to an event that we older people here have certainly not forgotten. In this place on Jan. 25, 1959, exactly 50 years ago, Blessed Pope John XXIII announced for this first time his desire to convoke “an ecumenical Council for the universal Church” (AAS LI [1959], p. 68). He made this announcement to the cardinals in the chapter room of the Monastery of St. Paul, after having celebrated solemn Mass in the Basilica.

From the providential decision, suggested to my venerable predecessor, according to his firm conviction, by the Holy Spirit, there also derived a fundamental contribution to ecumenism, condensed in the decree Unitatis Redintegratio. In that document we read: “There can be no ecumenism worthy of the name without a change of heart. For it is from renewal of the inner life of our minds, from self-denial and an unstinted love that desires of unity take their rise and develop in a mature way” (7).

The attitude of interior conversion in Christ, of spiritual renewal, of increased charity toward other Christians, created a new situation in ecumenical relations. The fruits of theological dialogues, with their convergences and with the more precise identification of the differences that still remain, led to a courageous pursuit in two directions: in the reception of what was positively achieved and a renewed dedication to the future.

Opportunely, the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, which I thank for the service it renders to all the disciples of the Lord, has recently reflected on the reception and future of ecumenical dialogue. Such a reflection, if on one hand rightly desires to emphasize what has already been achieved, on the other hand intends to find new ways to continue the relations between the Churches and the ecclesial Communities in the present context.

The horizon of full unity remains open before us. It is an arduous task, but it is exciting for those Christians who want to live in harmony with the prayer of the Lord: “that all be one so that the world believes” (John 17:21). The Second Vatican Council explained to us “that human powers and capacities cannot achieve this holy objective — the reconciling of all Christians in the unity of the one and only Church of Christ” (Unitatis redintegratio, 24).

Trusting in the prayer of the Lord Jesus Christ, and encouraged by the significant steps made by the ecumenical movement, with faith we invoke the Holy Spirit that he continue to illumine our path. May the Apostle Paul, who worked so hard and suffered for the unity of the mystical body of Christ, spur us on from heaven; and may the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the unity of the Church, accompany and sustain us.

Trusting in the prayer of the Lord Jesus Christ, and encouraged by the significant steps made by the ecumenical movement, with faith we invoke the Holy Spirit that he continue to illumine our path. May the Apostle Paul, who worked so hard and suffered for the unity of the mystical body of Christ, spur us on from heaven; and may the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the unity of the Church, accompany and sustain us.

Pope Benedict XVI

Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls

Vespers, Conversion of Saint Paul, 2009

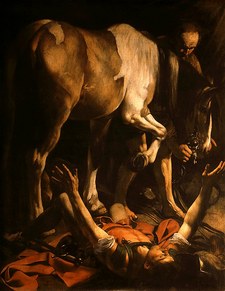

Conversion of Saint Paul

I planted, Apollo watered, but God gave the increase, Alleluia.

I planted, Apollo watered, but God gave the increase, Alleluia.

O thou great Doctor, Paul, we here beseech of thee Lead thou our spirits up to heavenly mystery,

Till ends the partial knowledge that to us is given, While here below, and we receive the fuller light in heaven.

May everlasting honor, power and glory be, And jubilation, to the Holy Trinity, The One God, ever ruling all things mightily, Throughout all endless ages of eternity. Amen.

O God, Who has taught the whole world by the preaching of the blessed Paul the Apostle; we beseech Thee, that we, who this day celebrate his conversion, may by his example advance unto Thee.

On this day 50 years ago (1959), Blessed Pope John XXIII, at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside-the-Walls, announced the Second Vatican Council.

Saint Paul & Art

Henry Artis, an artist and a modest theologian will give a presentation on St. Paul and Art (as part of the Crossroads on the Road program) this Sunday, January 11 at 12:00 noon, at the parish of Saint John Baptist de la Salle, 5706 Sargent Road, Chillum, MD 20782.

Henry Artis, an artist and a modest theologian will give a presentation on St. Paul and Art (as part of the Crossroads on the Road program) this Sunday, January 11 at 12:00 noon, at the parish of Saint John Baptist de la Salle, 5706 Sargent Road, Chillum, MD 20782.

The flyer is located

Seeing St Paul flyer – Maryland.pdf.

Mr. Artis is available to give or a similar presentation in your parish or school. Email me and I’ll put you in touch with him, paulzalonski@yahoo.com.

True Worship is communion with Christ, Pope says

On January 7, 2009, His Holiness delivered this address. It bears reading the whole thing. It is excellent, per usual!

In this first general audience of 2009, I want to offer all of you fervent best wishes for the New Year that just began. Let us renew our determination to open the mind and heart to Christ, to be and live as his true friends. His company will make this year, even with its inevitable difficulties, be a path full of joy and peace. In fact, only if we remain united to Jesus will the New Year be good and happy.

The commitment of union with Christ is the example that St. Paul offers us. Continuing the catecheses dedicated to him, we pause today to reflect on one of the important aspects of his thought, the worship that Christians are called to offer. In the past, there was a leaning toward speaking of an anti-worship tendency in the Apostle, of a “spiritualization” of the idea of worship. Today we better understand that St. Paul sees in the cross of Christ a historical change, which transforms and radically renews the reality of worship. There are above all three passages from the Letter to the Romans in which this new vision of worship is presented.

The commitment of union with Christ is the example that St. Paul offers us. Continuing the catecheses dedicated to him, we pause today to reflect on one of the important aspects of his thought, the worship that Christians are called to offer. In the past, there was a leaning toward speaking of an anti-worship tendency in the Apostle, of a “spiritualization” of the idea of worship. Today we better understand that St. Paul sees in the cross of Christ a historical change, which transforms and radically renews the reality of worship. There are above all three passages from the Letter to the Romans in which this new vision of worship is presented.

1. In Romans 3:25, after having spoken of the “redemption brought about by Christ Jesus,” Paul goes on with a formula that is mysterious to us, saying: God “set [him] forth as an expiation, through faith, by his blood.” With this expression that is quite strange for us — “instrument of expiation” — St. Paul refers to the so-called propitiatory of the ancient temple, that is, the lid of the ark of the covenant, which was considered a point of contact between God and man, the point of the mysterious presence of God in the world of man. This “propitiatory,” on the great day of reconciliation — Yom Kippur — was sprinkled with the blood of sacrificed animals, blood that symbolically put the sins of the past year in contact with God, and thus, the sins hurled to the abyss of the divine will were almost absorbed by the strength of God, overcome, pardoned. Life began anew.

St. Paul makes reference to this rite and says: This rite was the expression of the desire

that all our faults could really be put in the abyss of divine mercy and thus made to disappear. But with the blood of animals, this process was not fulfilled. A more real contact between human fault and divine love was necessary. This contact has taken place with the cross of Christ. Christ, Son of God, who has become true man, has assumed in himself all our faults. He himself is the place of contact between human misery and divine mercy; in his heart, the sad multitude of evil carried out by humanity is undone, and life is renewed.

that all our faults could really be put in the abyss of divine mercy and thus made to disappear. But with the blood of animals, this process was not fulfilled. A more real contact between human fault and divine love was necessary. This contact has taken place with the cross of Christ. Christ, Son of God, who has become true man, has assumed in himself all our faults. He himself is the place of contact between human misery and divine mercy; in his heart, the sad multitude of evil carried out by humanity is undone, and life is renewed.

Revealing this change, St. Paul tells us: With the cross of Christ — the supreme act of divine love, converted into human love — the ancient worship with the sacrifice of animals in the temple of Jerusalem has ended. This symbolic worship, worship of desire, has now been replaced by real worship: the love of God incarnated in Christ and taken to its fullness in the death on the cross. Therefore, this is not a spiritualization of the real worship, but on the contrary, this is the real worship, the true divine-human love, that replaces the symbolic and provisional worship. The cross of Christ, his love with flesh and blood, is the real worship, corresponding to the reality of God and man. Already before the external destruction of the temple, for Paul, the era of the temple and its worship had ended: Paul is found here in perfect consonance with the words of Jesus, who had announced the end of the temple and announced another temple “not made by human hands” — the temple of his risen body (cf. Mark 14:58; John 2:19 ff). This is the first passage.

2. The second passage about which I would like to speak today is found in the first verse of Chapter 12 of the Letter to the Romans. We have heard it and I repeat it once again: “I urge you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God, your spiritual worship.”

In these words, an apparent paradox is verified: While sacrifice demands as a norm the death of the victim, Paul makes reference to the life of the Christian. The expression “offer your bodies,” united to the successive concept of sacrifice, takes on the worship nuance of “give in oblation, offer.” The exhortation to “offer your bodies” refers to the whole person; in fact, in Romans 6:13, [Paul] makes the invitation to “present yourselves to God.” For the rest, the explicit reference to the physical dimension of the Christian coincides with the invitation to “glorify God in your bodies” (1 Corinthians 6:20): It’s a matter of honoring God in the most concrete daily existence, made of relational and perceptible visibility.

Conduct of this type is classified by Paul as “living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God.” It is here where we find precisely the term “sacrifice.” In prevalent use, this term forms part of a sacred context and serves to designate the throat-splitting of an animal, of which one part can be burned in honor of the gods and another part consumed by the offerers in a banquet. Paul instead applied it to the life of the Christian. In fact he classifies such a sacrifice by using three adjectives. The first — “living” — expresses a vitality. The second — “holy” — recalls the Pauline concept of a sanctity that is not linked to places or objects, but to the very person of the Christian. The third — “pleasing to God” — perhaps recalls the common biblical expression of a sweet-smelling sacrifice (cf. Leviticus 1:13, 17; 23:18; 26:31, etc.).

Immediately afterward, Paul thus defines this new way of living: this is “your spiritual worship.” Commentators of the text know well that the Greek expression (tçn logikçn latreían) is not easy to translate. The Latin Bible renders it: “rationabile obsequium.” The same word “rationabile” appears in the first Eucharistic prayer, the Roman Canon: In it, we pray so that God accepts this offering as “rationabile.” The traditional Italian translation, “spiritual worship,” [an offering in spirit], does not reflect all the details of the Greek text, nor even of the Latin. In any case, it is not a matter of a less real worship or even a merely metaphorical one, but of a more concrete and realistic worship, a worship in which man himself in his totality, as a being gifted with reason, transforms into adoration and glorification of the living God.

This Pauline formula, which appears again in the Roman Eucharistic prayer, is fruit of a long development of the religious experience in the centuries preceding Christ. In this experience are found theological developments of the Old Testament and currents of Greek thought. I would like to show at least certain elements of this development. The prophets and many psalms strongly criticize the bloody sacrifices of the temple. For example, Psalm 50 (49), in which it is God who speaks, says, “Were I hungry, I would not tell you, for mine is the world and all that fills it. Do I eat the flesh of bulls or drink the blood of goats? Offer praise as your sacrifice to God” (verses 12-14).

This Pauline formula, which appears again in the Roman Eucharistic prayer, is fruit of a long development of the religious experience in the centuries preceding Christ. In this experience are found theological developments of the Old Testament and currents of Greek thought. I would like to show at least certain elements of this development. The prophets and many psalms strongly criticize the bloody sacrifices of the temple. For example, Psalm 50 (49), in which it is God who speaks, says, “Were I hungry, I would not tell you, for mine is the world and all that fills it. Do I eat the flesh of bulls or drink the blood of goats? Offer praise as your sacrifice to God” (verses 12-14).

In the same sense, the following Psalm 51 (50), says, ” …for you do not desire sacrifice; a burnt offering you would not accept. My sacrifice, God, is a broken spirit; God, do not spurn a broken, humbled heart” (verse 18 and following).

In the Book of Daniel, in the times of the new destruction of the temple at the hands of the Hellenistic regime (2nd century B.C.), we find a new step in the same direction. In midst of the fire — that is, persecution and suffering — Azariah prays thus: “We have in our day no prince, prophet, or leader, no holocaust, sacrifice, oblation, or incense, no place to offer first fruits, to find favor with you. But with contrite heart and humble spirit let us be received; As though it were holocausts of rams and bullocks … So let our sacrifice be in your presence today as we follow you unreservedly” (Daniel 3:38ff).

In the destruction of the sanctuary and of worship, in this situation of being deprived of every sign of the presence of God, the believer offers as a true holocaust a contrite heart, his desire of God.

We see an important development, beautiful, but with a danger. There exists a spiritualization, a moralization of worship: Worship becomes only something of the heart, of the spirit. But the body is lacking; the community is lacking. Thus is understood that Psalm 51, for example, and also the Book of Daniel, despite criticizing worship, desire the return of the time of sacrifices. But it is a matter of a renewed time, in a synthesis that still was unforeseeable, that could not yet be thought of.

Let us return to St. Paul. He is heir to these developments, of the desire for true worship, in which man himself becomes glory of God, living adoration with all his being. In this sense, he says to the Romans: “Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice … your spiritual worship” (Romans 12:1).

Let us return to St. Paul. He is heir to these developments, of the desire for true worship, in which man himself becomes glory of God, living adoration with all his being. In this sense, he says to the Romans: “Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice … your spiritual worship” (Romans 12:1).

Paul thus repeats what he had already indicated in Chapter 3: The time of the sacrifice of animals, sacrifices of substitution, has ended. The time of true worship has arrived. But here too arises the danger of a misunderstanding: This new worship can easily be interpreted in a moralist sense — offering our lives we make true worship. In this way, worship with animals would be substituted by moralism: Man would do everything for himself with his moral strength. And this certainly was not the intention of St. Paul.

But the question persists: Then how should we interpret this “reasonable spiritual worship”? Paul always supposes that we have come to be “one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28), that we have died in baptism (Romans 1) and we live now with Christ, through Christ and in Christ. In this union — and only in this way — we can be in him and with him a “living sacrifice,” to offer the “true worship.” The sacrificed animals should have substituted man, the gift of self of man, and they could not. Jesus Christ, in his surrender to the Father and to us, is not a substitution, but rather really entails in himself the human being, our faults and our desire; he truly represents us, he assumes us in himself. In communion with Christ, accomplished in the faith and in the sacraments, we transform, despite our deficiencies, into living sacrifice: “True worship” is fulfilled.

This synthesis is the backdrop of the Roman Canon in which we pray that this offering be “rationabile,” so that spiritual worship is accomplished. The Church knows that in the holy Eucharist, the self-gift of Christ, his true sacrifice, is made present. But the Church prays so that the celebrating community is really united to Christ, is transformed; it prays so that we ourselves come to be that which we cannot be with our efforts: offering “rationabile” that is pleasing to God. In this way the Eucharistic prayer interprets in an adequate way the words of St. Paul.

St. Augustine clarified all of this in a marvelous way in the 10th book of his City of God. I cite only two phrase: “This is the sacrifice of the Christians: though being many we are only one body in Christ” … “All of the redeemed community (civitas), that is, the congregation and the society of the saints, is offered to God through the High Priest who has given himself up” (10,6: CCL 47,27ff).

3. Finally, I want to leave a brief reflection on the third passage of the Letter to the Romans referring to the new worship. St. Paul says thus in Chapter 15: “the grace given me by God to be a minister of Christ Jesus to the Gentiles in performing the priestly service (hierourgein) of the gospel of God, so that the offering up of the Gentiles may be acceptable, sanctified by the holy Spirit” (15:15ff).

I would like to emphasize only two aspects of this marvelous text and one aspect of the unique terminology of the Pauline letters. Before all else, St. Paul interprets his missionary action among the peoples of the world to construct the universal Church as a priestly action. To announce the Gospel to unify the peoples in communion with the Risen Christ is a “priestly” action. The apostle of the Gospel is a true priest; he does what is at the center of the priesthood: prepares the true sacrifice.

And then the second aspect: the goal of missionary action is — we could say in this way — the cosmic liturgy: that the peoples united in Christ, the world, becomes as such the glory of God “pleasing oblation, sanctified in the Holy Spirit.” Here appears a dynamic aspect, the aspect of hope in the Pauline concept of worship: the self-gift of Christ implies the tendency to attract everyone to communion in his body, to unite the world. Only in communion with Christ, the model man, one with God, the world comes to be just as we all want it to be: a mirror of divine love. This dynamism is always present in Scripture; this dynamism should inspire and form our life. And with this dynamism we begin the New Year. Thanks for your patience.

And then the second aspect: the goal of missionary action is — we could say in this way — the cosmic liturgy: that the peoples united in Christ, the world, becomes as such the glory of God “pleasing oblation, sanctified in the Holy Spirit.” Here appears a dynamic aspect, the aspect of hope in the Pauline concept of worship: the self-gift of Christ implies the tendency to attract everyone to communion in his body, to unite the world. Only in communion with Christ, the model man, one with God, the world comes to be just as we all want it to be: a mirror of divine love. This dynamism is always present in Scripture; this dynamism should inspire and form our life. And with this dynamism we begin the New Year. Thanks for your patience.

Christian ethics is born in friendship with Christ

In last Wednesday’s catechesis [11/19], I spoke of the question of how man is justified before God. Following St. Paul, we have seen that man is not capable of making himself “just” with his own actions, but rather that he can truly become “just” before God only because God confers on him his “justice,” uniting him to Christ, his Son. And man obtains this union with Christ through faith.

In last Wednesday’s catechesis [11/19], I spoke of the question of how man is justified before God. Following St. Paul, we have seen that man is not capable of making himself “just” with his own actions, but rather that he can truly become “just” before God only because God confers on him his “justice,” uniting him to Christ, his Son. And man obtains this union with Christ through faith.

In this sense, St. Paul tells us: It is not our works, but our faith that makes us “just.” This faith, nevertheless, is not a thought, opinion or idea. This faith is communion with Christ, which the Lord entrusts to us and that because of this, becomes life in conformity with him. Or in other words, faith, if it is true and real, becomes love, charity — is expressed in charity. Faith without charity, without this fruit, would not be true faith. It would be a dead faith.

We have therefore discovered two levels in the last catechesis: that of the insufficiency of our works for achieving salvation, and that of “justification” through faith that produces the fruit of the Spirit. The confusion between these two levels down through the centuries has caused not a few misunderstandings in Christianity.

In this context it is important that St. Paul, in the Letter to the Galatians, puts emphasis on one hand, and in a radical way, on the gratuitousness of justification not by our efforts, and, at the same time, he emphasizes as well the relationship between faith and charity, between faith and works. “For in Christ Jesus, neither circumcision nor uncircumcision counts for anything, but only faith working through love” (Galatians 5:6). Consequently, there are on one hand the “works of the flesh,” which are fornication, impurity, debauchery, idolatry, etc. (Galatians 5:19-21), all of which are contrary to the faith. On the other hand is the action of the Holy Spirit, which nourishes Christian life stirring up “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control” (Galatians 5:22): These are the fruits of the Spirit that arise from faith.

At the beginning of this list of virtues is cited ágape, love, and at the end, self-control. In reality, the Spirit, who is the Love of the Father and the Son, infuses his first gift, ágape, into our hearts (cf. Romans 5:5); and ágape, love, to be fully expressed, demands self-control. Regarding the love of the Father and the Son, which comes to us and profoundly transforms our existence, I dedicated my first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est. Believers know that in mutual love the love of God and of Christ is incarnated by means of the Spirit.

At the beginning of this list of virtues is cited ágape, love, and at the end, self-control. In reality, the Spirit, who is the Love of the Father and the Son, infuses his first gift, ágape, into our hearts (cf. Romans 5:5); and ágape, love, to be fully expressed, demands self-control. Regarding the love of the Father and the Son, which comes to us and profoundly transforms our existence, I dedicated my first encyclical, Deus Caritas Est. Believers know that in mutual love the love of God and of Christ is incarnated by means of the Spirit.

Let us return to the Letter of the Galatians. Here, St. Paul says that believers complete the command of love by bearing each other’s burdens (cf. Galatians 6:2). Justified by the gift of faith in Christ, we are called to live in the love of Christ toward others, because it is by this criterion that we will be judged at the end of our existence. In reality, Paul does nothing more than repeat what Jesus himself had said, and which we recalled in the Gospel of last Sunday, in the parable of the Final Judgment.

In the First Letter to the Corinthians, St. Paul becomes expansive with his famous praise of love. It is the so-called hymn to charity: “If I speak in human and angelic tongues but do not have love, I am a resounding gong or a clashing cymbal. … Love is patient, love is kind. It is not jealous, (love) is not pompous, it is not inflated, it is not rude, it does not seek its own interests …” (1 Corinthians 13:1,4-5).

Christian love is so demanding because it springs from the total love of Christ for us: this love that demands from us, welcomes us, embraces us, sustains us, even torments us, because it obliges us to live no longer for ourselves, closed in on our egotism, but for “him who has died and risen for us” (cf. 2 Corinthians 5:15). The love of Christ makes us be in him this new creature (cf. 2 Corinthians 5:17), who enters to form part of his mystical body that is the Church.

From this perspective, the centrality of justification without works, primary object of Paul’s preaching, is not in contradiction with the faith that operates in love. On the contrary, it demands that our very faith is expressed in a life according to the Spirit. Often, an unfounded contraposition has been seen between the theology of Paul and James, who says in his letter: “For just as a body without a spirit is dead, so also faith without works is dead” (2:26).

From this perspective, the centrality of justification without works, primary object of Paul’s preaching, is not in contradiction with the faith that operates in love. On the contrary, it demands that our very faith is expressed in a life according to the Spirit. Often, an unfounded contraposition has been seen between the theology of Paul and James, who says in his letter: “For just as a body without a spirit is dead, so also faith without works is dead” (2:26).

In reality, while Paul concerns himself above all with demonstrating that faith in Christ is necessary and sufficient, James highlights the consequent relationship between faith and works (cf. James 2:2-4). Therefore, for Paul and for James, faith operative in love witnesses to the gratuitous gift of justification in Christ. Salvation, received in Christ, needs to be protected and witnessed “with fear and trembling. For God is the one who, for his good purpose, works in you both to desire and to work. Do everything without grumbling or questioning … as you hold on to the word of life,” even St. Paul would say to the Christians of Philippi (cf. Philippians 2:12-14,16).

Often we tend to fall into the same misunderstandings that have characterized the community of Corinth: Those Christians thought that, having been gratuitously justified in Christ by faith, “everything was licit.” And they thought, and often it seems that the Christians of today think, that it is licit to create divisions in the Church, the body of Christ, to celebrate the Eucharist without concerning oneself with the brothers who are most needy, to aspire to the best charisms without realizing that they are members of each other, etc.

The consequences of a faith that is not incarnated in love are disastrous, because it is reduced to a most dangerous abuse and subjectivism for us and for our brothers. On the contrary, following St. Paul, we should renew our awareness of the fact that, precisely because we have been justified in Christ, we don’t belong to ourselves, but have been made into the temple of the Spirit and are called, therefore, to glorify God in our bodies and with the whole of our existence (cf. 1 Corinthians 6:19). It would be to scorn the inestimable value of justification if, having been bought at the high price of the blood of Christ, we didn’t glorify him with our body. In reality, this is precisely our “reasonable” and at the same time “spiritual” worship, for which Paul exhorts us to “offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God” (Romans 12:1).

To what would be reduced a liturgy directed only to the Lord but that doesn’t become, at the same time, service of the brethren, a faith that is not expressed in charity? And the Apostle often puts his communities before the Final Judgment, on which occasion “we must all appear before the judgment seat of Christ, so that each one may receive recompense, according to what he did in the body, whether good or evil” (2 Corinthians 5:10; and cf. Romans 2:16).

If the ethics that St. Paul proposes to believers does not lapse into forms of moralism, and if it shows itself to be current for us, it is because, each time, it always recommences from the personal and communitarian relationship with Christ, to verify itself in life according to the Spirit. This is essential: Christian ethics is not born from a system of commandments, but rather is the consequence of our friendship with Christ. This friendship influences life: If it is true, it incarnates and fulfills itself in love for neighbor. Hence, any ethical decline is not limited to the individual sphere, but at the same time, devalues personal and communitarian faith: From this it is derived and on this, it has a determinant effect.

If the ethics that St. Paul proposes to believers does not lapse into forms of moralism, and if it shows itself to be current for us, it is because, each time, it always recommences from the personal and communitarian relationship with Christ, to verify itself in life according to the Spirit. This is essential: Christian ethics is not born from a system of commandments, but rather is the consequence of our friendship with Christ. This friendship influences life: If it is true, it incarnates and fulfills itself in love for neighbor. Hence, any ethical decline is not limited to the individual sphere, but at the same time, devalues personal and communitarian faith: From this it is derived and on this, it has a determinant effect.

Let us, therefore, be overtaken by the reconciliation that God has given us in Christ, by God’s “crazy” love for us: No one and nothing could ever separate us from his love (cf. Romans 8:39). With this certainty we live. And this certainty gives us the strength to live concretely the faith that works in love.

Benedictus XVI

Pontiff of the Roman Church

26 November 2008

Faith and works in the process of our justification

In today’s general audience, the Pope said:

In our continuing catechesis on Saint Paul, we now consider his teaching on faith and works in the process of our justification. Paul insists that we are justified by faith in Christ, and not by any merit of our own. Yet he also emphasizes the relationship between faith and those works which are the fruit of the Holy Spirit’s presence and action within us. The first gift of the Spirit is love, the love of the Father and the Son poured into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Our sharing in the love of Christ leads us to live no longer for ourselves, but for him (cf. 2 Cor 5:14-15); it makes us a new creation (cf. 2 Cor 5:17) and members of his Body, the Church. Faith thus works through love (cf. Gal 5:6). Consequently, there is no contradiction between what Saint Paul teaches and what Saint James teaches regarding the relationship between justifying faith and the fruit which it bears in good works. Rather, there is a different emphasis. Redeemed by the precious blood of Christ, we are called to glorify him in our bodies (cf. 1 Cor 6:20), offering ourselves as a spiritual sacrifice pleasing to God. Justified by the gift of faith in Christ, we are called, as individuals and as a community, to treasure that gift and to let it bear rich fruit in the Spirit.

In our continuing catechesis on Saint Paul, we now consider his teaching on faith and works in the process of our justification. Paul insists that we are justified by faith in Christ, and not by any merit of our own. Yet he also emphasizes the relationship between faith and those works which are the fruit of the Holy Spirit’s presence and action within us. The first gift of the Spirit is love, the love of the Father and the Son poured into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Our sharing in the love of Christ leads us to live no longer for ourselves, but for him (cf. 2 Cor 5:14-15); it makes us a new creation (cf. 2 Cor 5:17) and members of his Body, the Church. Faith thus works through love (cf. Gal 5:6). Consequently, there is no contradiction between what Saint Paul teaches and what Saint James teaches regarding the relationship between justifying faith and the fruit which it bears in good works. Rather, there is a different emphasis. Redeemed by the precious blood of Christ, we are called to glorify him in our bodies (cf. 1 Cor 6:20), offering ourselves as a spiritual sacrifice pleasing to God. Justified by the gift of faith in Christ, we are called, as individuals and as a community, to treasure that gift and to let it bear rich fruit in the Spirit.

ARE WE CLEAR???????

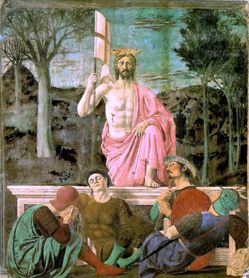

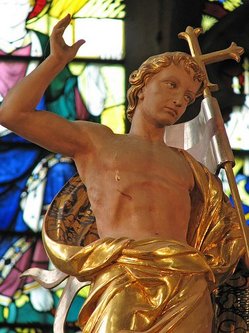

Saint Paul and the Resurrection

“And if Christ has not been raised, then empty is our preaching; empty, too, your faith. … You are still in your sins” (1 Corinthians 15:14,17). With these heavy words of the First Letter to the Corinthians, St. Paul makes clear how decisive is the importance that he attributes to the resurrection of Jesus. In this event, in fact, is the solution to the problem that the drama of the cross implies. On its own, the cross could not explain Christian faith; on the contrary, it would be a tragedy, a sign of the absurdity of being. The Paschal mystery consists in the fact that this Crucified One “was raised on the third day, according to the Scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:4) — thus testifies the proto-Christian witness.

Here is the central key to Pauline Christology: Everything revolves around this gravitational center point. The whole teaching of the Apostle Paul departs from and always arrives at the mystery of the One whom the Father has risen from the dead. The Resurrection is a fundamental fact, almost a previous basic assumption (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:12), in base of which Paul can formulate his synthetic proclamation (“kerygma”): He who has been crucified, and who has thus manifested the immense love of God for man, has risen and is alive among us.

It is important to note the link between the proclamation and the Resurrection, just as Paul formulates it, and that which was used in the first pre-Pauline Christian communities. Here one can truly see the importance of the tradition that preceded the Apostle and that he, with great respect and attention, wanted in turn to convey. The text on the Resurrection, contained in Chapter 15:1-11 of the First Letter to the Corinthians, emphasizes well the nexus between “receive” and “transmit.” St. Paul attributes great importance to the literal formulation of tradition; the end of the fragment we are examining highlights: “Whether it be I or they, so we preach and so you believed” (1 Corinthians 15:11), thus spotlighting the unity of the kerygma, of the proclamation for all believers and for all those who would announce the resurrection of Christ.

The tradition to which he unites is the fount from which to draw. The originality of his Christology is never in detriment to fidelity to tradition. The kerygma of the apostles always prevails over the personal re-elaboration of Paul; each one of his arguments flows from the common tradition, in which the faith shared by all the Churches, which are just one Church, is expressed.

And in this way, Paul offers a model for all times of how to do theology and how to preach. The theologian and the preacher do not create new visions of the world and of life, but rather are at the service of the truth transmitted, at the service of the real fact of Christ, of the cross, of the resurrection. Their duty is to help to understand today, behind the ancient words, the reality of “God with us,” and therefore, the reality of true life.

Here it is opportune to say precisely: St. Paul, in announcing the Resurrection, does not

concern himself with presenting an organic doctrinal exposition — he does not want to practically write a theology manual — but rather to take up the theme, responding to uncertainties and concrete questions that are posed him by the faithful. An episodic discourse, therefore, but full of faith and a lived theology. A concentration of the essential is found in him: We have been “justified,” that is, made just, saved, by Christ, dead and risen, for us. The fact of the Resurrection emerges above all else, without which Christian life would simply be absurd. On that Easter morning something extraordinary and new happened, but at the same time, something very concrete, verified by very precise signs, attested by numerous witnesses.

concern himself with presenting an organic doctrinal exposition — he does not want to practically write a theology manual — but rather to take up the theme, responding to uncertainties and concrete questions that are posed him by the faithful. An episodic discourse, therefore, but full of faith and a lived theology. A concentration of the essential is found in him: We have been “justified,” that is, made just, saved, by Christ, dead and risen, for us. The fact of the Resurrection emerges above all else, without which Christian life would simply be absurd. On that Easter morning something extraordinary and new happened, but at the same time, something very concrete, verified by very precise signs, attested by numerous witnesses.

Also for Paul, as for the other authors of the New Testament, the Resurrection is united to the testimony of those who have had a direct experience of the Risen One. It is about seeing and hearing not just with the eyes and the ears, but also with an interior light that motivates recognizing what the external senses verify as an objective datum. Paul therefore gives — as do the four Evangelists — fundamental relevance to the theme of the apparitions, which are a fundamental condition for faith in the Risen One who has left the tomb empty.

These two facts are important: The tomb is empty and Jesus really appeared. Thus is built this chain of tradition that, by way of the testimony of the apostles and the first disciples, would reach successive generations, up to us. The first consequence, or the first way to express this testimony, is preaching the resurrection of Christ as a synthesis of the Gospel message and as the culminating point of the salvific itinerary. All of this, Paul does on various occasions: One can consult the Letters and the Acts of the Apostles, where it can always be seen that the fundamental point for him is being a witness of the Resurrection.

I would like to cite just one text: Paul, under arrest in Jerusalem, is before the Sanhedrin as one accused. In this circumstance in which life and death are at stake, he indicates the meaning and the content of all his concern: “I am on trial for hope in the resurrection of the dead” (Acts 23:6). Paul repeats this same refrain often in his Letters (cf. 1 Thessalonians 1:9ff, 4:13-18; 5:10), in which he invokes his personal experience, his personal encounter with the resurrected Christ (cf. Galatians 1:15-16; 1 Corinthians 9:1).

But we can ask ourselves: What is, for St. Paul, the deep meaning of the event of the resurrection of Jesus? What does he say to us 2,000 years later? Is the affirmation “Christ has risen” also current for us? Why is the Resurrection for him and for us today a theme that is so determinant?

Paul solemnly responds to this question at the beginning of the Letter to the Romans, where he makes an exhortation referring to the “gospel of God … about his Son, descended from David according to the flesh, but established as Son of God in power according to the spirit of holiness through resurrection from the dead” (Romans 1:3-4).

Paul knows well and he says many times that Jesus was the Son of God always, from the moment of his incarnation. The novelty of the resurrection consists in the fact that Jesus, elevated from the humility of his earthly existence, has been constituted Son of God “with power.” The Jesus humiliated till death on the cross can now say to the Eleven: “All power on heaven and on earth has been given to me” (Matthew 28:18). What Psalm 2:8 says has been fulfilled: “Only ask it of me, and I will make your inheritance the nations, your possession the ends of the earth.”

That’s why with the resurrection begins the proclamation of the Gospel of Christ to all peoples — the Kingdom of Christ begins; this new Kingdom that does not know another power other than that of truth and love. The Resurrection therefore definitively reveals the authentic identity and the extraordinary stature of the Crucified: An incomparable and most high dignity — Jesus is God! For St. Paul, the secret identity of Jesus, even more than in the incarnation, is revealed in the mystery of the resurrection. While the title “Christ,” that is, “Messiah,” “Anointed,” in St. Paul tends to become the proper name of Jesus and that of Lord specifies his personal relationship with the believers, now the title Son of God comes to illustrate the intimate relationship of Jesus with God, a relationship that is fully revealed in the Paschal event. It can be said, therefore, that Jesus has risen to be the Lord of the living and the dead (cf. Romans 14:9 and 2 Corinthians 5:15) or, in other words, our Savior (cf. Romans 4:25).

All of this carries with it important consequences for our life of faith: We are called to participate from the depths of our being in the whole of the event of the death and resurrection of Christ. The Apostle says: We “have died with Christ” and we believe “that we shall also live with him. We know that Christ, raised from the dead, dies no more; death no longer has power over him” (Romans 6:8-9).

All of this carries with it important consequences for our life of faith: We are called to participate from the depths of our being in the whole of the event of the death and resurrection of Christ. The Apostle says: We “have died with Christ” and we believe “that we shall also live with him. We know that Christ, raised from the dead, dies no more; death no longer has power over him” (Romans 6:8-9).

This translates into sharing the sufferings of Christ, as a prelude to this full configuration with him through the resurrection, which we gaze upon with hope. This is also what has happened to Paul, whose experience is described in the Letters with a tone that is as much precise as realistic: “to know him and the power of his resurrection and (the) sharing of his sufferings by being conformed to his death, if somehow I may attain the resurrection from the dead” (Philippians 3:10-11; cf. 2 Timothy 2:8-12). The theology of the cross is not a theory — it is a reality of Christian life. To live in faith in Jesus Christ, to live truth and love implies renunciations every day; it implies sufferings. Christianity is not a path of comfort; it is rather a demanding ascent, but enlightened with the light of Christ and with the great hope that is born from him.

St. Augustine says: Christians are not spared suffering; on the contrary, they get a little extra, because to live the faith expresses the courage to face life and history more deeply. And with everything, only in this way, experiencing suffering, we experience life in its depth, in its beauty, in the great hope elicited by Christ, crucified and risen. The believer finds himself between two poles: on one side, the Resurrection, which in some way is already present and operative in us (cf. Colossians 3:1-4; Ephesians 2:6), and on the other, the urgency of fitting oneself into this process that leads everyone and everything to plenitude, as described in the Letter to the Romans with audacious imagination: As all of creation groans and suffers near labor pains, in this way we too groan in the hope of the redemption of our body, of our redemption and resurrection (cf. Romans 8:18-23).

In sum, we can say with Paul that the true believer obtains salvation professing with his lips that Jesus is Lord and believing in his heart that God has raised him from the dead (cf. Romans 10:9). Important above all is the heart that believes in Christ and in faith “touches” the Risen One. But it is not enough to carry faith in the heart; we should confess it and give testimony with the lips, with our lives, thus making present the truth of the cross and the resurrection in our history.

In this way, the Christian fits himself in this process thanks to which the first Adam, earthly and subject to corruption and death, goes transforming into the last Adam, heavenly and incorruptible (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:20 – 22:42-49). This process has been set in motion with the resurrection of Christ, in which is founded the hope of being able to also enter with Christ into our true homeland, which is heaven. Sustained with this hope, let us continue with courage and joy.

Pope Benedict XVI

November 2, 2008

Courtesy of Zenit.org

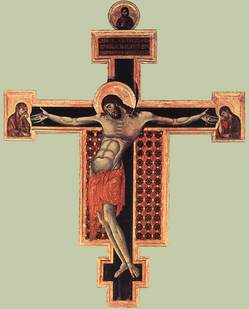

Pope Benedict on Saint Paul and the Cross

Vatican City State

October 29, 2008

Dear brothers and sisters:

In the personal experience of St. Paul, there is an indisputable fact: While at the beginning he had been a persecutor of the Christians and had used violence against them, from the moment of his conversion on the road to Damascus, he changed to the side of Christ crucified, making him the reason for his life and the motive for his preaching.

His was an existence entirely consumed by souls (cf. 2 Corinthians

serene and protected from snares and difficulties. In the encounter with Jesus, he had understood the central significance of the cross: He had understood that Jesus had died and risen for all and also for [Paul], himself. Both elements were important — the universality: Jesus had truly died for everyone; and the subjectivity: He had died also for me.

serene and protected from snares and difficulties. In the encounter with Jesus, he had understood the central significance of the cross: He had understood that Jesus had died and risen for all and also for [Paul], himself. Both elements were important — the universality: Jesus had truly died for everyone; and the subjectivity: He had died also for me.

On the cross, therefore, the gratuitous and merciful love of God had been manifested. Paul experienced this love above all in himself (cf. Galatians

For

Before a Church where disorders and scandals were present in a worrying way, where communion was threatened by groups and internal divisions that compromised the unity of the Body of Christ, Paul presents himself not with sublime words or wisdom, but with the announcement of Christ, of Christ crucified. His strength is not persuasive language, but rather, paradoxically, the weakness and the tremor of one who trusts only in the “power of God” (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:1-4). The cross, for everything that it represents and also for the theological message it contains, is scandal and foolishness. The Apostle affirms this with impressive strength, which is better to hear with his own words: “The message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. … It was the will of God through the foolishness of the proclamation to save those who have faith. For Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.”

The first Christian communities, whom Paul addressed, knew very well that Jesus is now risen and alive; the Apostle wants to remind not just the Corinthians and the Galatians, but all of us, that the Risen One is always the One who has been crucified. The “scandal” and the “foolishness” of the cross are precisely in the fact that there, where there seems to be only failure, sorrow and defeat, precisely there, is all the power of the limitless love of God, because the cross is the expression of love and love is the true power that is revealed precisely in this apparent weakness.

For the Jews, the cross is “skandalon,” that is, a trap or stumbling block: It seems to be an obstacle to the faith of the pious Israelite, who doesn’t manage to find anything similar in sacred Scripture. Paul, with no small amount of courage, seems to say here that the stakes are very high: For the Jews, the cross contradicts the very essence of God, who has manifested himself with prodigious signs. Therefore, to accept the cross of Christ means to undergo a profound conversion in the way of relating with God.

If for the Jews the reason to reject the cross is found in revelation, that is, in fidelity to the God of their fathers, for the Greeks, that is, the pagans, the criteria for judgment in opposing the cross is reason. For this latter group, in fact, the cross is blight, foolishness, literally insipience, that is, food lacking salt; therefore, more than an error, it is an insult to good sense.

Paul himself on more than one occasion had the bitter experience of the rejection of the Christian pronouncement judged “insipid,” irrelevant, not even worthy of being taken into consideration on the level of rational logic. For those who, like the Greeks, sought perfection in the spirit, in pure thought, it was already unacceptable that God became man, submerging himself in all the limits of space and time. Therefore it was decidedly inconceivable to believe that a God could end up on the cross! And we see how this Greek logic is also the common logic of our time.

The concept of “apátheia,” indifference, as absence of passions in God: How could it have understood a God made man and defeated, who later on even had taken up again his body so as to live resurrected? “We should like to hear you on this some other time” (Acts

But, why has

Centuries after Paul, we see that the cross, and not the wisdom that opposes the cross, has triumphed. The Crucified is wisdom, because he manifests in truth who God is, that is, the power of love that goes to the point of the cross to save man. God avails of ways and instruments that to us appear at first glance as only weakness. The Crucified reveals, on one hand, the weakness of man, and on the other, the true power of God, that is, the gratuitousness of love: Precisely this gratuitousness of love is true wisdom.

St. Paul has experienced this even in his flesh, and he gives us testimony of this in various passages of his spiritual journey, which have become essential reference points for every disciple of Jesus: “He said to me, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness'” (2 Corinthians 12:9); and even “God chose the lowly and despised of the world, those who count for nothing, to reduce to nothing those who are something” (1 Corinthians 1:28). The Apostle identifies himself to such a degree with Christ that he also, even in the midst of so many trials, lives in the faith of the Son of God who loved him and gave himself up for his sins and those of everyone (cf. Galatians 1:4; 2:20). This autobiographical detail of the Apostle is paradigmatic for all of us.

St. Paul offered an admirable synthesis of the theology of the cross in the Second Letter to the Corinthians (5:4-21), where everything is contained in two fundamental affirmations: On one hand, Christ, whom God has treated as sin on our behalf (verse 21), has died for us (verse 14); on the other hand, God has reconciled us with himself, not attributing to us our sins (verses 18-20). By this “ministry of reconciliation” all slavery has been purchased (cf. 1 Corinthians

Here it is seen how all of this is relevant for our lives. We also should enter into this

“ministry of reconciliation,” which always implies renouncing one’s own superiority and choosing the foolishness of love.

“ministry of reconciliation,” which always implies renouncing one’s own superiority and choosing the foolishness of love.

Saint Paul’s Christology: Radical Humility of Christ Is the Expression of Divine Love

Pope Benedict XVI address delivered during the general audience (10/22) in St. Peter’s Square.

Dear brothers and sisters:

In the catecheses from previous weeks, we have meditated on the “conversion” of St. Paul, fruit of a personal encounter with the crucified and risen Christ, and we have asked ourselves about the reaction of the Apostle to the Gentiles to the earthly Jesus. Today I would like to speak of the teaching St. Paul left us about the centrality of the risen Christ in the mystery of salvation, about his Christology.

In the catecheses from previous weeks, we have meditated on the “conversion” of St. Paul, fruit of a personal encounter with the crucified and risen Christ, and we have asked ourselves about the reaction of the Apostle to the Gentiles to the earthly Jesus. Today I would like to speak of the teaching St. Paul left us about the centrality of the risen Christ in the mystery of salvation, about his Christology.

In reality, the risen Jesus Christ, “exalted above every name,” is at the center of all his reflections. Christ is for the Apostle the standard to evaluate events and things, the purpose of every effort that he makes to announce the Gospel, the great passion that sustains his steps along the paths of the world. And he is a living Christ, concrete: The Christ, Paul says, “who loved me and gave himself up for me” (Galatians 2:20). This person who loves me, with whom I can speak, who listens and responds to me, this is really the principle for understanding the world and for finding the way in history.

Anyone who has read the writings of St. Paul knows well that he does not concern himself with narrating the events that made up the life of Christ, even though we can imagine that in his catecheses, he recounted much more about the pre-Easter Jesus than what he wrote in his letters, which are admonitions for concrete situations. His pastoral and theological work was so directed toward the edification of the nascent communities, that it was natural for him to concentrate everything on the announcement of Jesus Christ as “Lord,” alive today and present among his own.

Here we see the essentiality that is characteristic of Pauline Christology, which develops the depths of the mystery with a constant and precise concern: To announce, with certainty, Jesus and his teaching, but to announce above all the central reality of his death and resurrection as the culmination of his earthly existence and the root of the successive development of the whole Christian faith, of the whole reality of the Church.

For the Apostle, the Resurrection is not an event in itself that is separated from the Death.

The risen One is the same One who was crucified. The risen One also had his wounds: The Passion is present in him and it can be said with Pascal that he is suffering until the end of the world, though being the risen One and living with us and for us. Paul had understood on the road to Damascus this identification of the risen One with Christ crucified: In that moment, it was revealed with clarity that the Crucified is the risen One and the risen One is the Crucified, who says to Paul, “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4). Paul was persecuting Christ in the Church and then understood that the cross is “a curse of God” (Deuteronomy 21:23), but a sacrifice for our redemption.

The risen One is the same One who was crucified. The risen One also had his wounds: The Passion is present in him and it can be said with Pascal that he is suffering until the end of the world, though being the risen One and living with us and for us. Paul had understood on the road to Damascus this identification of the risen One with Christ crucified: In that moment, it was revealed with clarity that the Crucified is the risen One and the risen One is the Crucified, who says to Paul, “Why do you persecute me?” (Acts 9:4). Paul was persecuting Christ in the Church and then understood that the cross is “a curse of God” (Deuteronomy 21:23), but a sacrifice for our redemption.

The Apostle contemplates with fascination the hidden secret of the crucified-risen One, and through the sufferings endured by Christ in his humanity (earthly dimension) arrives to this eternal existence in which he is one with the Father (pre-temporal dimension): “But when the fullness of time had come,” he writes, “God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to ransom those under the law, so that we might receive adoption” (Galatians 4:4-5).

These two dimensions — the eternal pre-existence with the Father and the descent of the Lord in the incarnation — are already announced in the Old Testament, in the figure of Wisdom. We find in the wisdom literature of the Old Testament certain texts that exalt the role of Wisdom pre-existent to the creation of the world. In this sense, you can see passages such as Psalm 90: “Before the mountains were born, the earth and the world brought forth, from eternity to eternity you are God” (verse 2). Or passages such as those that speak of creating Wisdom: “The Lord begot me, the firstborn of his ways, the forerunner of his prodigies of long ago; From of old I was poured forth, at the first, before the earth” (Proverbs 8:22-23). Indicative as well is the praise of Wisdom, contained in the book by that name: “Indeed, she reaches from end to end mightily and governs all things well” (Wisdom 8:1).

The same wisdom texts that speak of the eternal pre-existence of Wisdom also speak of

its descent, of the abasement of this Wisdom, which has made for itself a tent among men. Thus we can already feel resonate the words from the Gospel of John that speak of the tent of the flesh of the Lord. A tent was created in the Old Testament: Here is indicated the temple, worship according to the “Torah”; but from the point of view of the New Testament, we can understand that this was only a pre-figuration of the much more real and significant tent: the tent of the flesh of Christ.

its descent, of the abasement of this Wisdom, which has made for itself a tent among men. Thus we can already feel resonate the words from the Gospel of John that speak of the tent of the flesh of the Lord. A tent was created in the Old Testament: Here is indicated the temple, worship according to the “Torah”; but from the point of view of the New Testament, we can understand that this was only a pre-figuration of the much more real and significant tent: the tent of the flesh of Christ.

And we already see in the books of the Old Testament that this abasement of Wisdom, its descent into flesh, also implies the possibility of being rejected. St. Paul, developing his Christology, refers precisely to this wisdom perspective: He recognizes in Jesus the eternal Wisdom existing from all time, the Wisdom that descends and creates a tent among us, and thus he can describe Christ as “the power of God and the wisdom of God.” He can say that Christ has become for us “wisdom from God, as well as righteousness, sanctification, and redemption” (1 Corinthians 1:24, 30). In the same way, Paul clarifies that Christ, like Wisdom, can be rejected above all by the rulers of this age (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:6-9), such that in the plans of God a paradoxical situation is created: the cross, which will become the path of salvation for the whole human race.

A later development to this wisdom cycle, which sees Wisdom abase itself so as to be later exalted despite rejection, is found in the famous hymn in the Letter to the Philippians (cf. 2:6-11). This involves one of the most elevated texts of the New Testament. Exegetes mainly concur in considering that this pericope was composed prior to the text of the Letter to the Philippians. This is an important piece of information, because it means that Judeo-Christianity, before St. Paul, believed in the divinity of Jesus. In other words, faith in the divinity of Christ is not a Hellenistic invention, arising after the earthly life of Christ, an invention that, forgetting his humanity, had divinized him. We see in reality that the early Judeo-Christianity believed in the divinity of Jesus. Moreover, we can say that the apostles themselves, in the great moments of the life of the Master, had understood that he was the Son of God, as St. Peter says at Caesarea Philippi: “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16).

But let us return to the hymn from the Letter to the Philippians. The structure of this text can be articulated in three stanzas, which illustrate the principle moments of the journey undertaken by Christ. His pre-existence is expressed with the words: “though he was in the form of God, [he] did not regard equality with God something to be grasped” (verse 6). Afterward follows the voluntary abasement of the Son in the second stanza: “he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (verse 7) “he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross” (verse 8). The third stanza of the hymn announces the response of the Father to the humiliation of the Son: “Because of this, God greatly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name” (verse 9).

What is impressive is the contrast between the radical abasement and the resulting glorification in the glory of God. It is evident that this second stanza contrasts with the pretension of Adam, who wanted to make himself God, and it contrasts as well with the actions of the builders of the Tower of Babel, who wanted to construct for themselves a bridge to heaven and make themselves divine. But this initiative of pride ended with self-destruction: In this way, one doesn’t arrive to heaven, to true happiness, to God. The gesture of the Son of God is exactly the contrary: not pride, but humility, which is the fulfillment of love, and love is divine. The initiative of abasement, of the radical humility of Christ, which contrasts with human pride, is really the expression of divine love; from it follows this elevation to heaven to which God attracts us with his love.

Besides the Letter to the Philippians, there are other places in Pauline literature where the themes of the pre-existence and the descent of the Son of God to earth are united. A reaffirmation of the assimilation between Wisdom and Christ, with all its cosmic and anthropological consequences, is found in the First Letter to Timothy: “[He] was manifested in the flesh, vindicated in the spirit, seen by angels, proclaimed to the Gentiles, believed in throughout the world, taken up in glory” (3:16). It is above all based on these premises that the function of Christ as mediator could be better defined, within the framework of the only God of the Old Testament (cf. 1 Timothy 2:5 in relation to Isaiah 43:10-11; 44:6). Christ is the true bridge who leads us to heaven, to communion with God.

And finally, just a point regarding the last developments of the Christology of St. Paul in the Letters to the Colossians and the Ephesians. In the first, Christ is designated as the “firstborn of all creation” (1:15-20). This word “firstborn” implies that the first among many children, the first among many brothers and sisters, has lowered to draw us and make us brothers and sisters. In the Letter to the Ephesians, we find the beautiful exposition of the divine plan of salvation, when Paul says that in Christ, God wanted to recapitulate all things (cf. Ephesians 1:23). Christ is the recapitulation of everything, he takes up everything and guides us to God. And thus is implied a movement of descent and ascent, inviting us to participate in his humility, that is, in his love for neighbor, so as to thus be participants in his glorification, making ourselves with him into sons in the Son. Let us pray that the Lord helps us to conform ourselves to is humility, to his love, to thus be participants in his divinization. (Zenit.org)

And finally, just a point regarding the last developments of the Christology of St. Paul in the Letters to the Colossians and the Ephesians. In the first, Christ is designated as the “firstborn of all creation” (1:15-20). This word “firstborn” implies that the first among many children, the first among many brothers and sisters, has lowered to draw us and make us brothers and sisters. In the Letter to the Ephesians, we find the beautiful exposition of the divine plan of salvation, when Paul says that in Christ, God wanted to recapitulate all things (cf. Ephesians 1:23). Christ is the recapitulation of everything, he takes up everything and guides us to God. And thus is implied a movement of descent and ascent, inviting us to participate in his humility, that is, in his love for neighbor, so as to thus be participants in his glorification, making ourselves with him into sons in the Son. Let us pray that the Lord helps us to conform ourselves to is humility, to his love, to thus be participants in his divinization. (Zenit.org)