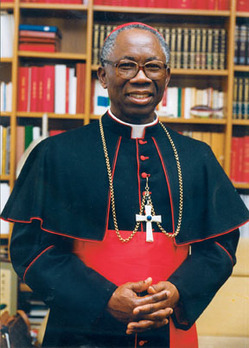

From March 1-7 you won’t be seeing too much Vatican activity since many, if not all, of the curial officials (the people who run the various Vatican offices for Pope’s apostolic ministry) are making their annual Lenten retreat. This year the retreat is being preached by Francis Cardinal Arinze, prefect emeritus of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments on the theme of “The priest encounters Jesus and follows him.”

From March 1-7 you won’t be seeing too much Vatican activity since many, if not all, of the curial officials (the people who run the various Vatican offices for Pope’s apostolic ministry) are making their annual Lenten retreat. This year the retreat is being preached by Francis Cardinal Arinze, prefect emeritus of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments on the theme of “The priest encounters Jesus and follows him.”

Cardinal Arinze was interviewed by the

Why did you choose this theme for the retreat of the Pope?

Cardinal Francis Arinze: I thought that in the meeting and following of Jesus, we are able to see a summary of all Christianity. On one side there is Jesus who calls us. On the other, we have with us our response: the encounter, so we follow and this becomes a program for life. It was like that for the first apostles: Jesus saw them and told them to follow him. In the following there includes listening to his teaching, miracles, prayer.

We can say that the apostles have completed three years in seminary and the rector was the Son of God. But the call of Jesus is not only for the priests.

Certainly, the reflections that are offered to the Pope are not only for priests but apply to everyone, because Christianity is about the encounter of Jesus with everyone. Everyone can apply it to himself, according to his vocation and mission. And each can give a different answer.

Among the disciples, there were those who immediately left their nets and became his disciples. But there were also those who remained attached to material things, asked for time, and wanted to first return to their loved ones before leaving.

Since then, two thousand years have passed. Can the man of today still meet Jesus?

If you want to, you can meet him, but always two major obstacles must be overcome. The first is superficiality, distraction. And the second is fear. Pontius Pilate is the paradigm of those who are afraid to face the truth. Jesus speaks to him, but he’s afraid. He says, “I have come to bear witness to the truth.” And Pilate asks, “What is truth?”

But his question is not that of a philosopher who is awaiting the reply. It’s one asked without listening, without waiting, without realizing that the truth is right in front of him. Even today many people are missing an appointment with the truth, because they are afraid of what Jesus is and his message. They do not realize that faith is not an obstacle to existence, but a promise of life and truth that goes beyond what is contingent.

Where can this meeting take place?

One of the key places — not physical but spiritual — is prayer. Prayer is to leave a space of silence for God, not only externally, but especially internally. You listen. The meditations I am giving the Pope will speak particularly of this, and will remember the long hours of prayer that Jesus spent alone, and will emphasize that the question the disciples asked: “Lord, teach us to pray”.

Another meeting place is in scripture: Jesus is the Word of God who became man. Scripture is the written Word of God. When we read the Bible and when we proclaim it during the liturgy, it is God who speaks. The Gospel is not a dusty book of the past. It is the voice of God today.

A third place is the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ. He himself has chosen this as the first pillar, he has given his guarantee that she will always be with you and has promised her the Holy Spirit. In the meditations I will emphasize this dimension: the Church is the Body of Christ, with Christ as the head. This is reflected in the liturgy where we meet Jesus, really and substantially, through Eucharistic communion. It is recognized in charity, especially towards the sick, the elderly, refugees, the poor. Jesus can speak in all these situations. Paul told us that the Church looks at the face of every suffering person and sees Jesus. We do not expect that Jesus will appear, because we are already close to him.

If for the Christian encountering Jesus means to follow Him, what happens when such an attitude of discipleship is missing from the priest?

It is Jesus who gives meaning to the life of the priest. Without him, the priest cannot understand, he no longer makes sense. I would say that his vocation becomes like a farce. For those who, in fact, celebrate, preach, and work?

Of course, it is possible that there are deficiencies in priests. Not all priests have been, and are, saints. The Gospel does not hide the weaknesses and falls of the disciples of Christ. There were those who asked Jesus to set fire to a city of

And then there is Judas Iscariot, who was with Jesus, but didn’t love him. He hardened his heart, closed it to him. This demonstrates that the human heart can fail, that the freedom given by God can be misused. In the history of the Church, unfortunately this has happened other times.

Can the penitential dimension of Lent help a priest renew his experience of his encounter with Christ?

Yes, starting with the act of receiving the ashes, which means to accept being sinners. The Church asks to pray a lot during Lent not only as a sign of adoration to God but also to repent of sins committed. It is not enough to receive forgiveness from God, we must also recognize that we have offended the love of God.

And then there is fasting to which the Pope has dedicated his Lenten message. It is today seen just as a gesture, but it should be understood in the proper meaning. Its true meaning is doing something pleasing for others such as sharing goods with the poor.

Solidarity with the suffering is also a way to show the authenticity of our Eucharistic celebration. At the end of Mass the priest says: Go and live what has been celebrated, heard, meditated and prayed. Helping those who are elderly, alone, imprisoned, disabled, is a way to live the Eucharist.

Benedict XVI clearly says this in Deus Caritas Est: If the Eucharist does not translate into works of charity it is fragmented, incomplete.

But shouldn’t we still recall the sobriety with which the Pope has re-launched his message of this year?

To fast is to accept that we are sinners. You do without something. It is also a means of spiritual ‘training’, similar to what athletes practice in order to succeed in a sport.

Then there is the most dynamic dimension, which is precisely that of helping the poor. Spend less and help our brothers who have not: it is the lifestyle advocated by the Pope in his message for World Day of Peace this year. The Christian spirit must go in the opposite direction with respect to unfettered consumerism.

Having beliefs and cabinets that are full — full of things that often we do not need or use just a few times — is an insult to the poor.