Category: Benedictine saints & blesseds

Saint Dunstan

Also on this date, the Benedictines recall the holy life of Saint Dunstan. Today’s Benedictine saint is very much revered by the Catholics of England –read up on him here.

Also on this date, the Benedictines recall the holy life of Saint Dunstan. Today’s Benedictine saint is very much revered by the Catholics of England –read up on him here.

“St Dunstan, as the story goes,

Once pull’d the devil by the nose

With red-hot tongs, which made him roar,

That he was heard three miles or more.”

(The Every-Day Book)

image by Fr Lawrence Lew, OP

Blessed Alcuin

The Benedictines remember today Blessed Alcuin of York who was born c. 735; died at Saint Martin’s in Tours, France, May 19, 804. Due to his education and experience in certain human matters, when Alcuin Charlemagne he impressed the emperor so much that he became his adviser. Alcuin was appointed abbot of Saint Martin’s Abbey at Tours (France) in 796 by Charlemagne. At Tours, with Saint Benedict of Aniane, he restored the monastic observance.

Toward the end of his life Alcuin said this of his own career with a rather beautiful description:

In the morning, at the height of my powers, I sowed the seed in Britain, now in the evening when my blood is growing cold I am still sowing in France, hoping both will grow, by the grace of God, giving some the honey of the holy scriptures, making others drunk on the old wine of ancient learning…

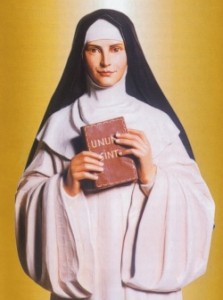

Blessed Maria Gabriella Sagheddu

Today, the Church honors a member of the Cistercian Order a blessed of the Church, an Italian nun, Blessed Maria Gabriella. A native of Sardinia, Italy born in 1914. Blessed Maria Gabriella was known to be given to willfulness, stubbornness and anger as a child and adolescent, but a conversion at 18 turned her will toward virtue and the love of Jesus Christ. Then, at 21, she entered a Cistercian monastery near Rome where she lived the contemplative, hidden life of a Trappistine nun. In her era, she likely knew nothing of the ‘ecumenical movement,’ at least not in any official way. In purity of heart –in a singular gesture– Sister Maria Gabriella offered her life for the Unity of the Church for all Christians.

Today, the Church honors a member of the Cistercian Order a blessed of the Church, an Italian nun, Blessed Maria Gabriella. A native of Sardinia, Italy born in 1914. Blessed Maria Gabriella was known to be given to willfulness, stubbornness and anger as a child and adolescent, but a conversion at 18 turned her will toward virtue and the love of Jesus Christ. Then, at 21, she entered a Cistercian monastery near Rome where she lived the contemplative, hidden life of a Trappistine nun. In her era, she likely knew nothing of the ‘ecumenical movement,’ at least not in any official way. In purity of heart –in a singular gesture– Sister Maria Gabriella offered her life for the Unity of the Church for all Christians.

In 1938, shortly after the offering of herself to the Lord, the symptoms of tuberculosis were diagnosed, and she died of this disease on April 23, 1939 (Good Shepherd Sunday), Her 15 months of suffering was an oblation.

On January 25, 1983, Pope John Paul II beatified her and named her patroness ‘of Unity’. She is a 20th century witness to our world that we have a responsibility for the restoration of the unity of Christians is the Love of Christ, personal conversion, sacrifice and prayer.

Let us pray,

O God, eternal shepherd, who inspired Blessed Maria Gabriella, virgin, to offer her life for the unity of all Christians, grant that through her intercession, the day may be hastened in which all believers in Christ, gathered around the table of your Word and of your Bread, may praise you with one heart and one voice. Through Christ our Lord.

Saint Anselm

The Church, in particular the Benedictines, liturgically remember the great Saint Anselm, monk and Archbishop of Canterbury (1034-1109). He is known for his writings on the existence of God and the meaning of Christ’s atonement on the cross. Many outside of the world of theology and monasticism would not really know of Anselm in any significant way. In short, we can say that he was “a monk with an intense spiritual life, an excellent teacher of the young, a theologian with an extraordinary capacity for speculation, a wise man of governance and an intransigent defender of the Church’s freedom…. [and he is] one of the eminent figures of the Middle Ages who was able to harmonize all these qualities, thanks to the profound mystical experience that always guided his thought and his action” (Pope Benedict XVI, Sept. 23, 2009). So, his monastic formation speaks clearly and forcefully than his ability to engage in secular or religious politics. In 1720, Pope Clement XI names Saint Anselm a Doctor of the Church.

The Church, in particular the Benedictines, liturgically remember the great Saint Anselm, monk and Archbishop of Canterbury (1034-1109). He is known for his writings on the existence of God and the meaning of Christ’s atonement on the cross. Many outside of the world of theology and monasticism would not really know of Anselm in any significant way. In short, we can say that he was “a monk with an intense spiritual life, an excellent teacher of the young, a theologian with an extraordinary capacity for speculation, a wise man of governance and an intransigent defender of the Church’s freedom…. [and he is] one of the eminent figures of the Middle Ages who was able to harmonize all these qualities, thanks to the profound mystical experience that always guided his thought and his action” (Pope Benedict XVI, Sept. 23, 2009). So, his monastic formation speaks clearly and forcefully than his ability to engage in secular or religious politics. In 1720, Pope Clement XI names Saint Anselm a Doctor of the Church.

I think the reflections of Dame Catherine –the Digitalnun– gives me (and hopefully you) a keen sense of why Anselm is relevant for us today: that being a person of intense prayer forms and informs all things for God’s greater glory. You can be gifted in many ways but knowing the Lord through prayer and sacrament is the only way to lead the Christian life. Everything else is secondary. This is what Sister Catherine said today:

For Anselm, as for many before and since, the whole venture of faith implies a connectedness, a rootedness in Christian tradition. Professor Denys Turner, one of the most perceptive of contemporary writers, argued very persuasively in the last chapter of his The Darkness of God: Negativity in Christian Mysticism that what so many now think of as ‘an experience of God’ had a wider meaning in former times. I think Anselm would have agreed that it is a phenomenon rooted in prayer, both public and private, in liturgy, in the sacramental worship of the Church and in theological reflection and exploration — moments of perception, of affirmation and negation, intended for the whole Church, not some specially privileged part of it. That is why the concept of sentire cum ecclesia, of thinking with the Church, is so essential.

Learning to think with the Church requires effort and self-discipline, finding out rather than simply opining. It is an activity rooted in prayer but calling for hard work, too. St Anselm was a great theologian because he was a man of prayer but also because he read — widely, attentively, thoughtfully — and because he put what he read and prayed into practice. We are not all called to be monastics, but shouldn’t every Christian be, to some degree, a theologian?

A brief biography is helpful

Saint Anselm was a native of Piedmont. When as a boy of fifteen he was forbidden to enter religion after the death of his good Christian mother, for a time he lost the fervor she had imparted to him. He left home and went to study in various schools in France; at length his vocation revived, and he became a monk at Bec in Normandy, where he had been studying under the renowned Abbot Lanfranc.

The fame of his sanctity in this cloister led King William Rufus of England, when dangerously ill, to take him for his confessor and afterwards to name him to the vacant see of Canterbury to replace his own former master, Lanfranc, who had been appointed there before him. He was consecrated in December, 1093. Then began the strife which characterized Saint Anselm’s episcopate. The king, when restored to health, lapsed into his former sins, continued to plunder the Church lands, scorned the archbishop’s rebukes, and forbade him to go to Rome for the pallium.

Finally the king sent envoys to Rome for the pallium; a legate returned with them to England, bearing it. The Archbishop received the pallium not from the king’s hand, as William would have required, but from that of the papal legate. For Saint Anselm’s defense of the Pope’s supremacy in a Council at Rockingham, called in March of 1095, the worldly prelates did not scruple to call him a traitor. The Saint rose, and with calm dignity exclaimed, If any man pretends that I violate my faith to my king because I will not reject the authority of the Holy See of Rome, let him stand, and in the name of God I will answer him as I ought. No one took up the challenge; and to the disappointment of the king, the barons sided with the Saint, for they respected his courage and saw that his cause was their own. During a time he spent in Rome and France, canons were passed in Rome against the practice of lay investiture, and a decree of excommunication was issued against offenders.

When William Rufus died, another strife began with William’s successor, Henry I. This sovereign claimed the right of investing prelates with the ring and crozier, symbols of the spiritual jurisdiction which belongs to the Church alone. Rather than yield, the archbishop went into exile, until at last the king was obliged to submit to the aging but inflexible prelate.

In the midst of his harassing cares, Saint Anselm found time for writings which have made him celebrated as the father of scholastic theology, while in metaphysics and in science he had few equals. He is yet more famous for his devotion to our Blessed Mother, whose Feast of the Immaculate Conception he was the first to establish in the West. He died in 1109.

Little Pictorial Lives of the Saints, a compilation based on Butler’s Lives of the Saints and other sources by John Gilmary Shea (Benziger Brothers: New York, 1894).

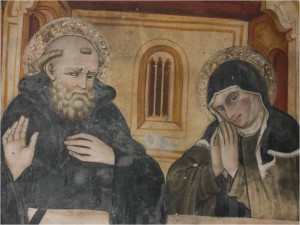

Saint Scholastica

From the Dialogues by Saint Gregory the Great:

From the Dialogues by Saint Gregory the Great:

Scholastica, the sister of Saint Benedict, had been consecrated to God from her earliest years. She was accustomed to visiting her brother once a year. He would come down to meet her at a place on the monastery property, not far outside the gate.

One day she came as usual and her saintly brother went with some of his disciples; they spent the whole day praising God and talking of sacred things. As night fell they had supper together.

Their spiritual conversation went on and the hour grew late. The holy nun said to her brother: “Please do not leave me tonight; let us go on until morning talking about the delights of the spiritual life.” “Sister,” he replied, “what are you saying? I simply cannot stay outside my cell.”

When she heard her brother refuse her request, the holy woman joined her hands on the table, laid her head on them and began to pray. As she raised her head from the table, there were such brilliant flashes of lightning, such great peals of thunder and such a heavy downpour of rain that neither Benedict nor his brethren could stir across the threshold of the place where they had been seated. Sadly he began to complain: “May God forgive you, sister. What have you done?” “Well,” she answered, “I asked you and you would not listen; so I asked my God and he did listen. So now go off, if you can, leave me and return to your monastery.”

Reluctant as he was to stay of his own will, he remained against his will. So it came about that they stayed awake the whole night, engrossed in their conversation about the spiritual life.

It is not surprising that she was more effective than he, since as John says, God is love, it was absolutely right that she could do more, as she loved more.

Three days later, Benedict was in his cell. Looking up to the sky, he saw his sister’s soul leave her body in the form of a dove, and fly up to the secret places of heaven. Rejoicing in her great glory, he thanked almighty God with hymns and words of praise. He then sent his brethren to bring her body to the monastery and lay it in the tomb he had prepared for himself.

Their minds had always been united in God; their bodies were to share a common grave.

St Rabanus Maurus Magnentius

Saint Rabanus Maurus Magnentius (c. 780 – 4 February 856), as a Frankish Benedictine monk, the archbishop of Mainz in Germany and a theologian. In his spare time he authored the encyclopaedia De rerum naturis (On the Nature of Things) and treatises on education, grammar and the Bible.

Saint Rabanus Maurus Magnentius (c. 780 – 4 February 856), as a Frankish Benedictine monk, the archbishop of Mainz in Germany and a theologian. In his spare time he authored the encyclopaedia De rerum naturis (On the Nature of Things) and treatises on education, grammar and the Bible.Benedictine Martyrs

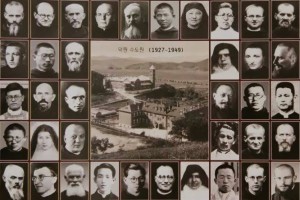

Monks and nuns are prime candidates in being martyrs for the Catholic Faith. Today, the Benedictine Congregation of St Ottilien (a missionary group of missionary monks) collectively honor those who shed their blood for Christ between the years of 1889 and 1954. Laying down one’s own life by accepting death bears witness to faith in Jesus Christ and His Church.

Monks and nuns are prime candidates in being martyrs for the Catholic Faith. Today, the Benedictine Congregation of St Ottilien (a missionary group of missionary monks) collectively honor those who shed their blood for Christ between the years of 1889 and 1954. Laying down one’s own life by accepting death bears witness to faith in Jesus Christ and His Church.

Many of these monks died in Asia and Africa.

Saint Maurus and Saint Placidus

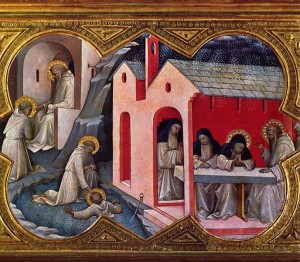

Benedictines have today as the feast day of Saint Maurus and Saint Placidus, disciples of Saint Benedict. What sticks out in peoples minds about Maurus is the relation he has with Benedict’s impressive miracles. The miracle is recounted by Pope Saint Gregory the Great in chapter 7 of the Second Book of his Dialogues:

Benedictines have today as the feast day of Saint Maurus and Saint Placidus, disciples of Saint Benedict. What sticks out in peoples minds about Maurus is the relation he has with Benedict’s impressive miracles. The miracle is recounted by Pope Saint Gregory the Great in chapter 7 of the Second Book of his Dialogues:

“On a certain day, as the venerable Benedict was in his cell, the young Placidus, one of the Saint’s monks, went out to draw water from the lake; and putting his pail into the water carelessly, fell in after it. The water swiftly carried him away, and drew him nearly a bowshot from the land. Now the man of God, though he was in his cell, knew this at once, and called in haste for Maurus, saying: ‘Brother Maurus, run, for the boy who went to the lake to fetch water, has fallen in, and the water has already carried him a long way off!’

What does the miraculous gesture of Saint Benedict show us? The raising of Placidus challenges what we typically believe about truth and reality and our disordered desire to be constantly in control. Benedict tells us that we are not in control –only God is. The ordering of our human desires requires us to be in alignment with God’s Holy Will. This episode also illustrates Benedict’s point in the monastic tradition and spoken of in the Rule of mutual obedience –the listening to each other and the following the lead of the superior. On one level mutual obedience teaches a fraternal reliance on one another; on a higher level, mutual obedience is a distinct form of listening to the Holy Spirit. The Spirit is manifests Himself in the discerning and holy activity of people who have their hearts and minds attuned to God’s Voice.

Blessed Jutta of Disibodenberg

Until I read somewhere else today, I never heard of Blessed Jutta of Disibodenberg (c. 1084-1136), a German noble woman, an anchoress, and the teacher of children, especially Saint Hildegaard of Bingen.

Blessed Jutta’s history says that taught female students from wealthy families at her hermitage. She taught and raised them all, most notably the child Hildegard of Bingen.

Jutta was known for her sanctity and her life of extraordinary penance; Justta was known as a healer.

On the Day of All Saints, November 1, 1112, Hildegard was given over as a Benedictine oblate into the care of Jutta. It was Jutta who taught Hildegard to write; to read the psalms used in the Liturgy; to chant the recitation of the Canonical hours. She probably also taught Hildegard to play the zither-like string instrument called the psaltery.

Saint Hildegaard of Bingen, succeeded Jutta as abbess; Benedict XVI named Hildegard a Doctor of the Church and we would make the claim that she owes her fundamental knowledge of life to Blessed Jutta. Let us pray for those who were our first teachers of life and faith.