Read Boston Globe’s Michael Paulson’s article on the renewed interest in perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. It’s picking up steam in Boston, why not in other dioceses?

Author: Paul Zalonski

The Madeleine turns 100

Utah’s Catholics are celebrating a 100 years of the Catholic cathedral’s presence in a state long known as a haven for Mormons. The mother church of the diocese, The Cathedral of the Madeleine, is 100 years old. While history shows us that Franciscan missionaries preached and celebrated Mass as early as 1776, this celebration concretizes a presence in a house of prayer that has celebrated the sacraments unto salvation.

Utah’s Catholics are celebrating a 100 years of the Catholic cathedral’s presence in a state long known as a haven for Mormons. The mother church of the diocese, The Cathedral of the Madeleine, is 100 years old. While history shows us that Franciscan missionaries preached and celebrated Mass as early as 1776, this celebration concretizes a presence in a house of prayer that has celebrated the sacraments unto salvation.

Saint Lawrence

Thou hast crowned him with glory and honor, O Lord. And hast set him over the works of Thy hands.

Lawrence the Deacon performed a pious act by giving sight to the blind through the sign of the Cross, and bestowed upon the poor the riches of the Church. (Vigil Magnificat Antiphon)

We beseech Thee, almighty God, grant us to quench the flames of our vices, even as Thou gavest blessed Lawrence grace to overcome his fiery torments.

The saintly deacon was asked by the Roman Prefect to hand over the Church’s wealth. needing three days to do so, he gathered thousands of lepers, blind and sick people, the poor, the widows and orphans and the elderly and presented them to the Prefect. Angry, the Prefect killed Lawrence slowly by roasting him on a gridiron. Saying to his torturers, “I am done on that side, turn me over,” died with a prayer for Rome’s conversion to Christ on his lips. The has honored Lawrence with texts for Mass and the Divine Office thinking very highly of his witness to Christ and service to the Church.

Knowing & praying God’s name is blessed in us

God may be made holy by our prayers but that His name may be hallowed in us…It

is because He commands us, ‘Be holy, even as I am holy,’ that we ask and

entreat that we who were sanctified in baptism may continue in that which we

have begun to be. And this we pray for daily, for we have need of daily

sanctification, that we who daily fall away may wash our sins by continual

sanctification.”

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross (Edith Stein)

God our Father, You give us joy each year in honoring the memory of Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross. May her prayers be a source of help for us, and may her example of courage and chastity be our inspiration.

Saint Dominic de Guzman

Preach we now the Word of life,

Not with show of worldly learning,

But with fervor of our faith

Open hearts to Spirit’s yearning.

Christ alone be ever knowing,

And Him crucified be showing.

Dominic, called by the Lord,

Preaching, teaching, daily blessing,

Living poor and common life,

Contemplation’s fruit expressing;

Thus he formed his Preachers boldly,

Showing graces manifoldly.

God the blessed Three in One,

Love beyond all human telling,

Father, Son, and Spirit blest,

Throned in heav’n and with us dwelling,

With the Word of Truth now feed us,

In Your holy ways now lead us.

78 78 88

suggested tune: Liebster Jesu

James Michael Thompson, (c) 2009, World Library Publications

Broadening our concept of reason & its application is indispensable, Pope said

In this context, the theme of integral human development

takes on an even broader range of meanings: the correlation between its

multiple elements requires a commitment to foster the interaction of the

different levels of human knowledge in order to promote the authentic

development of peoples. Often it is thought that development, or the

socio-economic measures that go with it, merely require to be implemented

through joint action. This joint action, however, needs to be given direction,

because “all social action involves a doctrine“. In view of the complexity of

the issues, it is obvious that the various disciplines have to work together

through an orderly interdisciplinary exchange. Charity does not exclude

knowledge, but rather requires, promotes, and animates it from within.

Knowledge is never purely the work of the intellect. It can certainly be

reduced to calculation and experiment, but if it aspires to be wisdom capable

of directing man in the light of his first beginnings and his final ends, it

must be “seasoned” with the “salt” of charity. Deeds without knowledge are

blind, and knowledge without love is sterile. Indeed, “the individual who is animated

by true charity labours skilfully to discover the causes of misery, to find the

means to combat it, to overcome it resolutely.” Faced with the phenomena that

lie before us, charity in truth requires first of all that we know and

understand, acknowledging and respecting the specific competence of every level

of knowledge. Charity is not an added extra, like an appendix to work already

concluded in each of the various disciplines: it engages them in dialogue from

the very beginning. The demands of love do not contradict those of reason.

Human knowledge is insufficient and the conclusions of science cannot indicate

by themselves the path towards integral human development. There is always a

need to push further ahead: this is what is required by charity in truth. Going

beyond, however, never means prescinding from the conclusions of reason, nor

contradicting its results. Intelligence and love are not in separate

compartments: love is rich in intelligence and intelligence is full of love.

This

means that moral evaluation and scientific research must go hand in hand, and

that charity must animate them in a harmonious interdisciplinary whole, marked

by unity and distinction. The Church’s social doctrine, which has “an important

interdisciplinary dimension”, can exercise, in this perspective, a function of

extraordinary effectiveness. It allows faith, theology, metaphysics and science

to come together in a collaborative effort in the service of humanity. It is

here above all that the Church’s social doctrine displays its dimension of

wisdom. Paul VI had seen clearly that among the causes of underdevelopment

there is a lack of wisdom and reflection, a lack of thinking capable of

formulating a guiding synthesis for which “a clear vision of all economic, social,

cultural and spiritual aspects” is required. The excessive segmentation of

knowledge, the rejection of metaphysics by the human sciences, the difficulties

encountered by dialogue between science and theology are damaging not only to

the development of knowledge, but also to the development of peoples, because

these things make it harder to see the integral good of man in its various

dimensions. The “broadening [of] our concept of reason and its application” is

indispensable if we are to succeed in adequately weighing all the elements

involved in the question of development and in the solution of socio-economic

problems.

(Caritas in veritate, 30-31; emphasis mine)

Subsidiarity lacks with the President

Msgr Lorenzo Albacete points to a lack of understanding of the principle of subsidiarity that’s going to challenge President Obama’s healthcare reform work. AND what is the principle of subsidiarity? It’s principle that nothing should be done at macro level that ought to be done at the micro level. So, the state should not impose its method on a municipality because the municipality ought to find a solution. If it can’t then you move up to the next reasonable level. See a sketch of the principle.

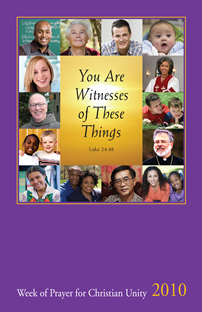

2010 Week of Prayer for Christian Unity: You are witness of these things

Since 1908 the Church has called upon us to join in prayer with

other Christians around the world during the Week of Prayer for Christian

Unity. We do this work of prayer as an education in hope for spiritual and actual Christian unity realizing that the Holy Spirit is the only one capable of bring unity among various groups of Christians. The proposal for a week of prayer was initiated in the USA by Franciscans of the Atonement Father Paul

Wattson and it is held from January 18 – 25. Today the observance is international in scope.

It is generally held that the 1910

World Mission Conference in Edinburgh, Scotland, marked the beginnings of the

modern ecumenical movement.

In tribute, the promoters of the Week of Prayer for

Christian Unity, the Commission on Faith and Order and the Pontifical Council for

Promoting Christian Unity, invited the Scottish churches to prepare this year’s

theme. They suggested: “You are

witnesses of these things” (Luke 24:48).

The 2010 theme is a reminder that as the

community of faith those reconciled with God and in Christ, “You are witness of

these things“–witness to the truth of the power of salvation in Jesus Christ

who will also make real his prayer,

“That all may be one…so the world may believe.” *Witness gives praise

to the Presence who gives us the gift of life and resurrection; by knowing how

to share the story of our faith with others; by recognizing that God is at work

in our lives; by giving thanks for the faith we have received; by confessing

Christ’s victory over all suffering; by seeking to always be more faithful to

the Word of God; by growing in faith, hope and love; and by offering

hospitality and knowing how to receive it when it is offered to us.

Materials

to observe the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity are available from the

Graymoor Ecumenical and Interreligious Institute, a ministry of the Franciscan Friars

of the Atonement.

For more information visit www.geii.org

Transfiguration of the Lord

Christ Jesus, the brightness of the Father and the image of His substance, upholding all things by the word of His power, effecting man’s purgation from sin, has deigned to appear this day in glory on a high mountain.