The Church honored Saint Philip Neri on May 25th. His memory in history leads me to ask more about his place in the Church and the work of bringing others to the Lord. Father Fred Miller, a priest of the Archdiocese of Newark, earned a doctorate in sacred theology from the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome. He is presently teaching systematic theology at Mt. St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, MD. Here is something to consider…

Since his canonization in 1622, Saint Philip Neri has been considered a model of priestly life and holiness among the clergy of Italy. One might say that Saint Philip has there the popularity enjoyed by Saint John Vianney among diocesan priests in the United States. For a variety of reasons, Saint Philip has had little notoriety among priests in North America. However, there seems to be a change. Many priests and seminarians are reading biographies of the “Apostle of Rome” and envisioning his approach to the priesthood for themselves. The foundation of new Oratories of Saint Philip throughout the USA also indicates interest in the saint.

Since his canonization in 1622, Saint Philip Neri has been considered a model of priestly life and holiness among the clergy of Italy. One might say that Saint Philip has there the popularity enjoyed by Saint John Vianney among diocesan priests in the United States. For a variety of reasons, Saint Philip has had little notoriety among priests in North America. However, there seems to be a change. Many priests and seminarians are reading biographies of the “Apostle of Rome” and envisioning his approach to the priesthood for themselves. The foundation of new Oratories of Saint Philip throughout the USA also indicates interest in the saint.

This essay does not intend to be either a detailed biography of the saint or a treatise on priestly holiness as exemplified in the life of Saint Philip Neri. This composition emerged as random reflections on the saint for a seminarian, now a priest, who had discovered Saint Philip during his seminary years. I present it in this venue in the hope that more priests will find in Saint Philip Neri a congenial confrere in the priesthood and a model of priestly life and holiness.

Might it not be said that an attraction to a particular saint has its origin above in the Holy Spirit and the intercession of God’s holy ones? In his encyclical letter Deus Caritas Est,Pope Benedict XVI pointed out that the saints continue to do in heaven what they had done on earth: “The lives of the saints are not limited to their earthly biographies but also include their being and working in God after death. In the saints one thing becomes clear: those who draw near to God do not withdraw from men, but rather become truly close to them.”1 One may conjecture that Saint Philip Neri, who was spiritual father to so many priest-sons while on earth, continues to exercise the ministry of priestly formation from his place in heaven. My sole intention is to point priests in the direction of an exemplary parish priest, the knowledge of whom will hopefully benefit them as well as the people they serve.

Renaissance and Reformation

Saint Philip Neri (1515 – 1595), a native of Florence, lived all of his life as a parish priest in Rome, the major center of the rebirth (Renaissance) of pagan culture in sixteenth-century Europe. He was also a contemporary of the Protestant Reformers. Renaissance and Reformation form the context of the exercise of Philip Neri’s priestly ministry.

John Henry Newman has noted that Saint Philip did not wage a frontal attack on the Renaissance, as did another native of Florence, Girolamo Savanarola. This charismatic Dominican friar saw little if anything good in the restoration of pagan culture and prophetically envisioned the so-called Enlightenment that would inevitably follow in its wake. In his desperation, the firebrand advocated destroying books, works of art, musical instruments, etc. as a necessary purgation of the Church. Linking the decadence of the clergy to the Renaissance, Savanarola ranted against the materialism and secularism of the Church’s leaders, denouncing bishops and even the pope.

On the other hand, Philip Neri, who, in fact, always venerated Savanarola as a saint, chose a different approach. While rejecting the immoral and decadent elements of his century, Philip, first as a layman and then as a priest, seized upon the good elements of the Renaissance and utilized them for the glorification of God. Historians have recognized Philip’s love of music, art, letters and history as well as his use of these arts in his catechetical ministry and, most especially, in his approach to the liturgy.

Palestrina, his spiritual directee, composed many of his polyphonic masterpieces for Saint Philip and the oratory meetings. Philip built one of the most beautiful Renaissance churches in Rome. He promoted the study of literature, patristics, the history of liturgy and ecclesiastical history, as well as catechesis for children. The Chiesa Nuova, his church, became a center of liturgical excellence in both the execution of the sacred rites and the use of sacred music.

Philip recognized the secular humanism of the Renaissance for exactly what it was: Christian charity separated from its life-giving ecclesial roots. An authentic Christian humanism, the humanism of the Gospel, was the foundation of Philip’s ministry of personal relationships. He understood that God effected conversions through the priest’s personal influence as friend, teacher, confessor, father and spiritual guide. One might speculate that Saint Philip would have been very much at home with the Christian personalism of Pope John Paul II and his theology of the body.

Philip was aware that the grace of conversion — communicated by God primarily through preaching the Gospel, the teaching of Catholic doctrine and the practice of frequent confession — has it first effects within the human heart, and then manifests itself in personal transformations that are often startling. In the recognition of how powerful the adoration of the Blessed Sacrament is in the process of conversion, Saint Philip spent much of his free time as a layman promoting the Forty Hours Devotion in Rome. His zeal for this devotion continued after his priestly ordination.

As a priest, Philip never called attention to a corrupt hierarchy. There was no need to do that. Sad to say, it was all too obvious. Rather, Philip lived the priesthood so joyfully and simply that he attracted worldly clerics by his priestly way of life. His tools were simple: frequent confession, daily mental prayer, and spiritual direction.

Although the Protestant Reformation did not directly influence the Church in Italy, Philip was aware that something dark and harmful was happening in the Lord’s vineyard. Philip lived his priesthood in a Church torn apart by heresy, schism and even cruel martyrdom. He had a particular love and concern for the seminarians of the Venerable English College in Rome. He was aware that the majority of these students, once ordained priests, would return to England and ultimately shed their blood as martyrs for Christ and his Church. To this day, the seminarians of the English College sing first vespers on the Solemnity of Saint Philip Neri at theChiesa Nuova in honor of the Roman priest who blessed their forebears on their way to martyrdom.

Historians have opined that Saint Philip played a large role in protecting Rome from the intrusion of the errors of Protestantism. He did this in at least three ways.

First, he organized a prayer group known as the Oratory for young people. The youth would gather in his presbytery each week, or several times a week, to read and discuss Sacred Scripture, to pray spontaneously, to sing hymns and to present ferverinos (short and fervent presentations on a theme assigned by Saint Philip) on Christian doctrine, the virtues and the lives of the saints.

In effect, Philip, by introducing the young to a form of lectio divina, taught them to pray with the Scriptures. Their presentations on doctrine and the lives of the saints helped the young to interpret the Scriptures within the sacred tradition of the Church. At the same time, Father Philip was preparing his spiritual children to explain the faith to their contemporaries and defend it whenever necessary, especially if Reformation thought found its way into Italy. In effect, Saint Philip’s prayer meetings formed contemplative apologists of the faith.

The French Oratorian Louis Bouyer offers this description of the Oratory meetings: “The program of their meetings took some ten years to crystallize into the following form: reading with commentary, the commentary taking the form of a conversation, followed by an exhortation by some other speaker. This would be followed in turn by a talk on Church history, with finally, another reading with a commentary, this time from the life of some saint. All this was interspersed with short prayers, hymns and music, and the service always finished with the singing of a new motet or anthem. It was taken for granted that everyone could come and go as they chose, as Philip himself did. He and the other speakers used to sit quite informally on a slightly raised bench facing the gathering.”2

Interesting to note, the centrality of Scripture in the Oratory meetings, the spontaneity of the prayer and hymnody, the instructions and exhortations presented by laymen, as well as the charismatic tone of the gatherings led some high-ranking ecclesiastics to accuse Philip of introducing his spiritual directees to a Protestant form of worship.

Second, Saint Philip assigned his most gifted disciple, Caesar Baronius, then just twenty years old, to research and present a talk each week on the history of the Church, beginning with Pentecost and ending at the present moment in the Church’s life. Baronius, a layman at the time, had no experience, and indeed little interest, in Church history; nevertheless he accepted the task in obedience to his spiritual father. Over the course of three years he completed his lectures, at which point Saint Philip told him to start again at the beginning. Over nearly thirty years, he had repeated the course of talks seven times, making many revisions and additions along the way. Around 1584, Philip finally commissioned Baronius to begin preparing a text demonstrating that the Church of the sixteenth century was the same in all essential aspects as the Church born on Pentecost. Baronius’ Annales Ecclesiastici in twelve volumes was finally completed near the end of Baronius’ rather long life. This text, which is still considered a classic of historical research, struck right at the heart of Luther’s assertion that the Roman Church had long ago broken communion with the pristine church of the apostles — the church that he imagined himself to be refounding in the sixteenth century.

Third, so resplendent was the character of Holy Orders in Philip Neri that people easily perceived the Lord Jesus preaching, sanctifying and shepherding his flock through and in him. The anemic brand of ministry proposed by Luther and Calvin paled in the glow of Philip’s witness to the apostolic succession of bishops and priests.

Precisely through this priesthood, the Church of every age has immediate contact with the authority and power Christ gave to Peter, Paul, the other apostles and the presbyters appointed by them to lead the burgeoning Christian communities after Pentecost. By rejecting the priesthood and, in so doing, breaking the apostolic succession, Luther did exactly what he accused the Roman Church of doing — breaking the Church’s life-giving connection with Christ and the apostles. Philip was a living, dramatic witness of the continuity.

Surely Saint Philip’s way of living the priesthood was as important a component of the Counter Reformation as was Ignatius Loyola’s establishment of an army of missionary priests ready to serve wherever the pope would send them, Borromeo’s witness to the teaching office of the bishop in the implementation of the Roman Catechism in the life of the local church, and Francis de Sales’ testimony to the sanctifying office of the bishop in his availability to direct the spiritual lives of the priests and laypersons in his care. Philip, it would seem, was raised up by God to exemplify how the apostolic ministry is to be exercised by priests in a stable manner precisely where God’s people live — that is, in parishes.

A secular priest: The Apostle of Rome

To this day, Saint Philip is known as the Apostle of Rome. It is said that whereas Saints Peter and Paul first converted the Romans through the preaching of the Gospel and baptism, Saint Philip reconverted them during the Renaissance through his ministry of spiritual direction and confession.

For forty-five years of his long life, Saint Philip served the Church as a secular priest in Rome. Although he died as an Oratorian, Saint Philip never intended to found a new congregation for priests. Rather, the Congregation of the Oratory sprang up around him as a result of his personal influence, his witness to personal prayer, his zeal to catechize the young and bring them to the sacraments, and his ever-joyful spirit.

Other priests enjoyed living, praying and doing apostolic work with him. They found it wholesome and liberating to follow the pattern he had established in his life as a parish priest of Rome. The fact that the Oratorians rightly claim Saint Philip as their founder should not dissuade priests from seeing him as an exemplary model for the diocesan clergy.

Newman’s conference The Mission of Saint Philip Neri, Louis Bouyer’s lyrical essay The Roman Socrates and Father Paul Turks’ biography of the saint, Fire of Joy, each in its own way, help form a concept of the personality and sanctity of this unusual priest. These texts illustrate the priest’s particular path to holiness: pastoral charity as practiced by Saint Philip, a holy and attractive exemplar of priestly life and holiness.

An emblematic mosaic of the saint

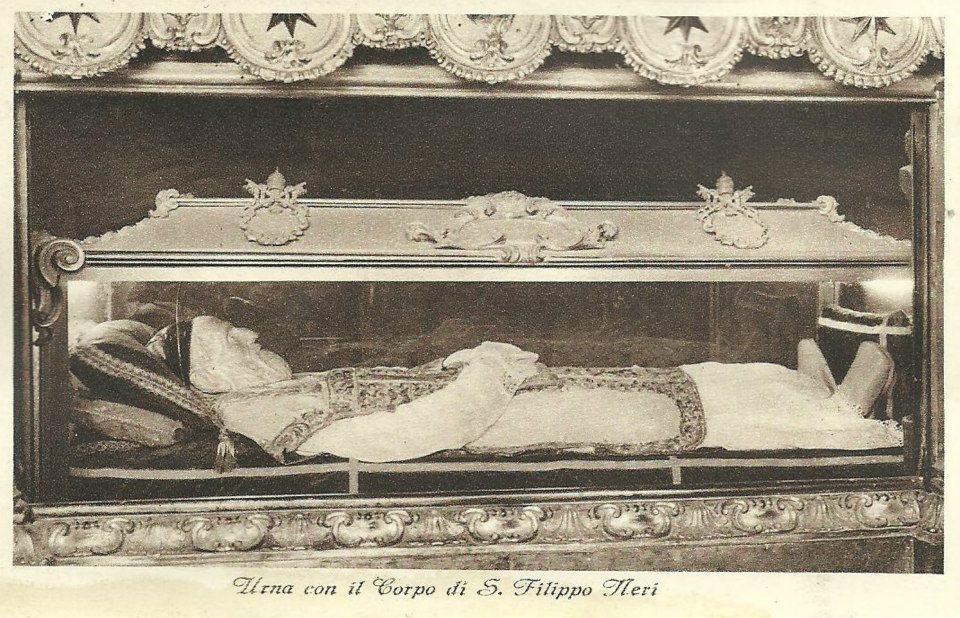

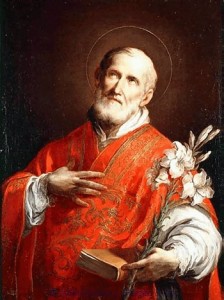

Over the altar that enshrines Saint Philip’s body in the Chiesa Nuova is a striking mosaic by Guido Reni. The artist presents the saint in red Mass vestments that simultaneously reveal the centrality of the Holy Spirit and the Holy Eucharist in Saint Philip’s life. The red vestments also indicate that Philip Neri lived the priesthood with the generosity and abandonment of the Christian martyrs. He kneels before our Blessed Mother, and there are lilies symbolizing his chastity and the fatherly love that was the fruit of his purity of heart.

The mosaic is a kind of emblem of Philip’s priestly ministry: the Eucharistic sacrifice at the center of everything he did, pastoral charity practiced with the zeal of the martyrs and the strength that comes from the Spirit of God, the spiritual motherhood of the Blessed Virgin that makes everything wholesome and fruitful. Philip’s posture in relationship to our Blessed Mother bespeaks the entrustment of one’s life and work to her that would later be described so powerfully by Saint Louis-Marie de Montfort in his classic, True Devotion to Mary.

Saint Philip Neri is a model of everything that is essential and real in the Catholic priesthood. He teaches priests that it is possible to be very active in apostolic works and a contemplative at the same time.

A priest filled with the Holy Spirit

As a young layman in Rome, Philip Neri spent his days visiting the sick in the hospitals, teaching children catechism, serving men and women who had come to Rome on pilgrimage, and, as already mentioned, promoting the Forty Hours Devotion in the churches of the city. He spent his nights praying deep down in the catacombs of Saint Sebastian.

In the course of one of these prayer vigils Saint Philip experienced his personal Pentecost. He saw the Holy Spirit coming towards him as fire — a fire that found its way into his heart. This experience led Philip to discuss the possibility of a priestly vocation with his spiritual director.

Saint Philip and the evangelical counsels

As a priest, the presence of the Holy Spirit was palpable in everything Father Philip said and did. Stated simply, he became a kind of living Pentecost; a Pentecostal event always ready to happen. This divine fire led Philip to embrace the priesthood in a radical, evangelical way. He chose to live as a poor man, dependent on Divine Providence for everything. Later, he would encourage his priest sons at Christmas time to give the poor any money they may have accumulated in the course of the year.

Saint Philip’s biographers say that he practiced perfect chastity. He understood that true spiritual fatherhood is in large measure the fruit of the abnegation involved in chastity.

Hearing tales of the Protestant Reformation in Germany, the Low Countries and in England, Philip was absolutely convinced that, in spite of the corruption in the Church of his day, the truth of Christ and his grace rested in the Catholic Church. He was obedient to the Church in all matters, great and small. Perhaps it was his appreciation of obedience that drew him into friendship with a neighbor who lived down the street, Ignatius of Loyola.

Saint Philip lived the Gospel counsels so completely that one sees in him the poverty of a Franciscan, the mortification of the flesh of a Carthusian, the obedience of the first Jesuits, the zeal of Saint Dominic and his white-robed friars to propagate the faith through preaching and teaching, and the dedication to the liturgy and contemplation of a Benedictine monk. Interestingly, Saint Philip felt very much at home with these religious, admired their particular charisms, and lived them, as he was able, as a diocesan priest.

Priestly mysticism in action

Saint Philip always carried the writings of the Desert Fathers in his cassock. Having been spiritually formed by the Conferences of John Cassian, Philip lived a simple, mortified life — a kind of monastic life — while living in the world and making himself available to serve his people.

In his interior life, contemplation and priestly work were wonderfully integrated. When he prayed — and Father Philip prayed for hours every day — he held his spiritual children in his heart. When he served them directly, he was consciously loving and serving Jesus in them. Centuries later, a son of Saint Philip, John Henry Newman, followed his spiritual father’s practice. As a very old man, he would sit in chapel with a notebook containing names and prayer intentions. He would spend hours holding one person after another up in prayer to the mercy of Christ. Both men understood that humble intercession is the core of true Christian prayer and an essential component in the life of a priest.

The Holy Spirit sometimes manifested himself in extraordinary ways when Saint Philip heard confession and gave spiritual direction. The penitent would hear the beating of the saint’s heart and feel heat emanating from his body — physical revelations of the presence of the Holy Spirit. Sometimes the saint revealed a hidden or forgotten sin to a careless and startled penitent. At other times, there would be a word of prophecy, bringing warning or consolation. The ordinary manifestations of the Holy Spirit in the lives of his penitents were the grace of confessing one’s sins without fear or anxiety, the peace that filled the soul of the reconciled sinner, freedom from the bondage of habitual sin, the sense of the presence of the Heavenly Father, a renewed commitment to one’s duties, and a greater power to love God and neighbor.

A Eucharistic mysticism

At the center of Saint Philip’s spiritual life was the daily celebration of the Holy Eucharist. At the beginning of his priesthood, Saint Philip lived with another priest who spent himself promoting frequent, even daily reception of the Holy Eucharist, a practice not common in those times. Saint Philip admired and supported this apostolate, but took another approach. His focus was frequent confession for the sake of the worthy and fruitful reception of the Holy Eucharist.

Philip was always surrounded by joy and laughter. People, young and old, loved to be in his company. There was always a lot of fun going on around Philip jokes, pranks, teasing and buffoonery. Philip used this lure to attract souls to Christ. He encouraged all to go to confession frequently. Since people loved to be with him, they came in large numbers and often to receive the sacrament. Philip attracted people through his personality — not to himself, but to Christ. In a sense, Philip Neri is a perfect specimen of the genius of the priesthood. He demonstrates that priests should want to be loved by their people. This love is the bridge whereby the good priest leads his people not to himself, but rather, through himself, to Christ.

It seems that Saint Philip spent as much time as Saint John Vianney hearing confessions. Why? He spent long hours in the confessional to reconcile sinners with God, to bring them inner peace, to create a culture of Christian love. Above all, though, Saint Philip Neri, like all the great priest-saints, was so devoted to confession precisely because of his love for the Holy Eucharist. He wanted everyone to love Christ as he deserves to be loved and to receive him worthily and fruitfully.

For Saint Philip, hearing confession was a kind of mystical prayer. Acting in persona Christi, Saint Philip experienced the powerful presence of the Holy Spirit in him, cleansing consciences and forming the penitents in the image of Christ. In this sense, he has a kinship with Saint John Vianney, Saint Padre Pio, and Saint Leopold Mandic. Saint Philip would likely tell priests that contemplative prayer is always accessible to them in preaching and teaching Catholic doctrine, in celebrating Mass, and in hearing confessions. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are never closer or more active than in the outpouring of their love through priestly mediation.

As an old man, Saint Philip spent hours each day on the roof of the Chiesa Nuova contemplating the mysteries of God as he looked out over the city of Rome and the mountains that surround it. His confreres often, and not always in a good mood, climbed the many flights of stairs leading to the roof to tell the father that one of his many penitents was waiting for confession. Without hesitation or any annoyance, Saint Philip would leave his prayer to hear the confession. He would interrupt his prayer on the roof saying that he was leaving Jesus to go to Jesus.

Saint Philip insisted that the church building, the altar, the linens and the vestments be immaculate and as beautiful as possible. He inspired the Renaissance musician, Palestrina, to write polyphonic music for Mass. Saint Philip’s priestly spirituality was riveted on the Holy Eucharist. Everything he did, from preaching, catechesis, and his work with youth to confession and spiritual direction, had one end — to lead people to union with Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

Saint Philip also loved the public solemnization of the Liturgy of the Hours. Sunday Vespers was an important moment in the life of Philip’s parishes. He grasped the intimate relationship that exists between the Eucharist and the Hours and wanted to bring the faithful into the mystery.

Saint Philip received many mystical graces when he celebrated Mass, graces that he tried to hide from the view of the people. When he started having these mystical experiences during Mass, he had someone read jokes to him on the way from the sacristy into the church. He hoped that this would distract him enough to be able to get through Mass without an ecstasy. Late in his life, he was unable to preach and celebrate Mass in public because of the physical effects of these mystical graces.

Preaching, he would go into ecstasy at the mention of the name of Jesus. He would spend two to three hours in ecstatic thanksgiving after receiving Holy Communion. There are records that he sometimes levitated during the celebration of the Holy Eucharist in the parish church.

There is a strange attitudinal phenomenon among some Catholics today that has persisted in the Church for centuries. It is the unfortunate dichotomy that exists in some people’s minds between liturgy and prayer. The Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours are looked upon as public worship. Real prayer, it is presumed, begins when one makes his or her Holy Hour or enters into a period of meditation or imaginative contemplation.

This attitude would be, I think, incomprehensible and abhorrent to Saint Philip Neri. For him, the prayer of prayers was the Mass (and the Hours). He held as an article of faith that the Eucharist is nothing less than the real presence of Christ and the re-presentation of his life-giving sacrifice. He also understood that Christ is truly present, but in different ways, in the other sacraments. The fact that the risen Christ lives and acts in the sacraments that he instituted was the foundation of the mystical life that Philip Neri experienced as a priest.

Philip sought to follow Jesus’ command: Pray always! However, there would be no question in his mind that all personal prayer flows directly from the Eucharist and the other sacraments and leads back to the most mystic of all experiences, the consecration of the bread and wine at Mass. Likewise, Saint Philip knew and taught that charity in all its manifestations flows directly from the Eucharist and leads the Christian back to a more perfect offering of the sacrifice.

In other words, for Philip the Eucharist, in a sense, was perpetuated in time and manifested its fruitfulness whenever he heard confessions or directed souls, visited and anointed the sick, prepared young couples to receive the sacrament of matrimony, taught children the catechism, helped the poor, or washed the feet of pilgrims. Saint Philip teaches us that the spiritual life is one and that the Eucharist is the integrating center of everything the priest does.

There are many other things that might be highlighted from the life of Saint Philip: his sense of humor, his ability to help people not take themselves too seriously, his many charismatic gifts at the service of forming men and women in the Christian life, his knack of forming humble and zealous priests, his understanding of the place of Sacred Scripture in preaching and in personal prayer, his appreciation of the history of the Church and the role of the cult of the saints in everyday life, and his disdain for clericalism and clerical ambition. The biographies tell the stories and illustrate the wisdom of this holy priest who lived in the splendor of the Italian Renaissance as if he was a first generation Christian in Jerusalem or pagan Rome.

The apostolate of personal influence

Philip chose to exercise his priesthood primarily by influencing people one by one. He made friends with people, loved them, and drew them into the heart of Christ precisely through love. Philip Neri is not remembered as a great preacher, a renowned theologian, or a brilliant administrator. His genius lay in his ability to enter into authentic and appropriate human relationships with men and women so as to unite them to Christ in the church’s sacraments. His brilliance was in the realm of personal influence though relationships. Only the Lord knows how many peoples’ lives he influenced in the confessional, in spiritual direction, and through the counsel offered in so many different situations.

John Henry Newman has admirably described Philip’s charismatic gift — the facility of drawing men and women to Christ, particularly in the sacrament of penance: “He allured men to the service of God so dexterously, and with such a holy, winning art, that those who saw it cried out, astonished: ‘Father Philip draws souls as the magnet draws iron.’ He so accommodated himself to the temper of each, as, in the words of the Apostle, to become ‘all things to all men, that he might gain all.’ And his love of them individually was so tender and ardent, that, even in extreme old age, he was anxious to suffer for their sins; and for this end he inflicted on himself severe disciplines, and he reckoned their misdeeds as his own, and wept for them as such.”3

At a time in the life of the Church in North America when, as a result of the terrible sexual crimes that have scarred the face of the priesthood, priests fear or at least are apprehensive about entering into appropriate priestly relationships, especially with the young, Saint Philip Neri is a model par excellence of the priest who loves all of his people for the sake of uniting them to Christ. Saint Philip understood that his celibacy freed him to love Christ with an undivided heart and to give himself chastely to all of God’s people.

A profound love for the mother of God

One may not describe the life and ministry of Saint Philip Neri without at least one word on his profound and childlike love for the mother of God. Philip, it seems, was often indecisive. When he was building the Chiesa Nuova he frequently changed the plans. On several occasions he indicated that the main aisle was not long enough. Through his regular vacillations, Philip drove the construction workers to despair. One morning, Philip walked into the unfinished church. Our Blessed Mother appeared to him holding up the central beam of the ceiling. He sent the workers up the scaffolding to learn that Our Lady was indeed the only reason the roof had not collapsed. Saint Philip teaches priests that this is the kind of confidence the true priest should have in Mary’s heavenly intercession.

John Henry Cardinal Newman, a disciple of Saint Philip Neri through all the years of his priesthood, describes Saint Philip’s way of priestly holiness and the kind of priests who sought out his company and his spiritual direction. Perhaps Saint Philip through his personal influence will today inspire many contemporary priests to be priests after his heart:

I would beg for you this privilege, that the public world might never know you for praise or for blame, that you should do a good deal of hard work in your generation, and prosecute many useful labors, and effect a number of religious purposes, and send many souls to heaven, and take men by surprise, how much you were really doing, when they happened to come near enough to see it; but that by the world you should be overlooked, that you should not be known out of your place, that you should work for God alone with a pure heart and single eye, without the distractions of human applause, and should make him your sole hope, and his eternal heaven your sole aim, and have your reward, not partly here, but fully and entirely hereafter.4

End Notes

1. Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, 42.

2. Louis Bouyer of the Oratory, The Roman Socrates — A Portrait of Saint Philip. Trans. by Michael Day. Westminster, Maryland, the Newman Press, 1958.

3. John Henry Newman, The Mission of Saint Philip II, 7.

4. John Henry Newman, The Mission of Saint Philip Neri

© Ignatius Press

One of the epitaphs of Saint Philip Neri’s is:

One of the epitaphs of Saint Philip Neri’s is: