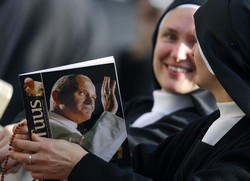

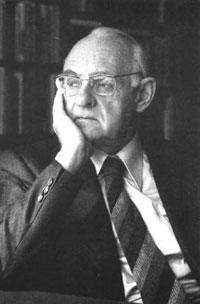

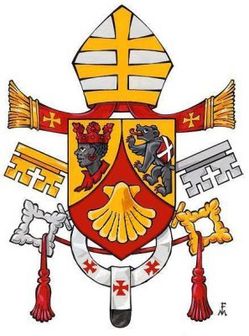

This 1995 essay by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) is a marvelous piece to meditate on today. Faith and communion, freedom and personal integration in God are relevant topics in our era where there is a lack of understanding of the basics of Christian faith. Without mentioning his name and his work, the author points to Msgr. Giussani’s Communion and Liberation and other ecclesial movements.

Let me begin with a brief story from the early postconciliar period. The Council documents – particularly the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, but also the decrees on ecumenism, on mission, on non-Christian religions, and on freedom of religion – had opened up broad vistas of dialogue for the Church and theology. New issues were appearing on the horizon, and it was becoming necessary to find new methods. It seemed self-evident that a theologian who wanted to be up to date and who rightly understood his task should temporarily suspend the old discussions and devote all of his energies to the new questions pressing in from every side.

At about this time, I sent a small piece of mine to Hans Urs von Balthasar. Balthasar

replied by return mail on a correspondence card, as he always did, and, after expressing his thanks, added a terse sentence that made an indelible impression on me: Do not presuppose the faith but propose it. This was an imperative that hit home. Wide-ranging exploration of new fields was good and necessary, but only so long as it issued from, and was sustained by, the central light of faith.

replied by return mail on a correspondence card, as he always did, and, after expressing his thanks, added a terse sentence that made an indelible impression on me: Do not presuppose the faith but propose it. This was an imperative that hit home. Wide-ranging exploration of new fields was good and necessary, but only so long as it issued from, and was sustained by, the central light of faith.

Faith is not maintained automatically. It is not a “finished business” that we can simply take for granted. The life of faith has to be constantly renewed. And since faith is an act that comprehends all the dimensions of our existence, it also requires constantly renewed reflection and witness. It follows that the chief points of faith – God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, grace and sin, sacraments and Church, death and eternal life -are never outmoded. They are always the issues that affect us most profoundly. They must be the permanent center of preaching and therefore of theological reflection. The bishops present at the 1985 Synod called for a universal catechism of the whole Church because they sensed precisely what Balthasar had put into words in his note to me. Their experience as shepherds had shown them that the various new pastoral activities have no solid basis unless they are irradiations and applications of the message of faith. Faith cannot be presupposed; it must be proposed. This is the purpose of the Catechism. It aims to propose the faith in its fullness and wealth, but also in its unity and simplicity.

What does the Church believe? This question implies another: Who believes, and how does someone believe? The Catechism treats these two main questions, which concern, respectively, the “what” and the “who” of faith, as an intrinsic unity. Expressed in other terms, the Catechism displays the act of faith and the content of faith in their indivisible unity. This may sound somewhat abstract, so let us try to unfold a bit what it means. We find in the creeds two formulas: “I believe” and “We believe.” We speak of the faith of the Church, of the personal character of faith and finally of faith as a gift of God, as a “theological act”, as contemporary theology likes to put it. What does all of this mean?

Faith is an orientation of our existence as a whole. It is a fundamental option that affects every domain of our existence. Nor can it be realized unless all the energies of our existence go into maintaining it. Faith is not a merely intellectual, or merely volitional, or merely emotional activity -it is all of these things together. It is an act of the whole self, of the whole person in his concentrated unity. The Bible describes faith in this sense as an act of the “heart” [Romans 10:9].

Faith is a supremely personal act. But precisely because it is supremely personal, it

transcends the self, the limits of the individual. Augustine remarks that nothing is so little ours as our self. Where man as a whole comes into play, he transcends himself; an act of the whole self is at the same time always an opening to others, hence, an act of being together with others (Mitsein). What is more, we cannot perform this act without touching our deepest ground, the living God who is present in the depths of our existence as its sustaining foundation.

transcends the self, the limits of the individual. Augustine remarks that nothing is so little ours as our self. Where man as a whole comes into play, he transcends himself; an act of the whole self is at the same time always an opening to others, hence, an act of being together with others (Mitsein). What is more, we cannot perform this act without touching our deepest ground, the living God who is present in the depths of our existence as its sustaining foundation.

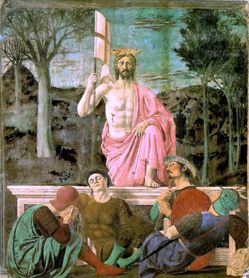

Any act that involves the whole man also involves, not just the self, but the we-dimension, indeed, the wholly other “Thou”, God, together with the self. But this also means that such an act transcends the reach of what I can do alone. Since man is a created being, the deepest truth about him is never just action but always passion as well; man is not only a giver but also a receiver. The Catechism expresses this point in the following words: “No one can believe alone, just as no one can live alone. You have not given yourself faith as you have not given yourself life.” Paul’s description of his experience of conversion and baptism alludes to faith’s radical character: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me” [Galatians 2,20]. Faith is a perishing of the mere self and precisely thus a resurrection of the true self. To believe is to become oneself through liberation from the mere self, a liberation that brings us into communion with God mediated by communion with Christ.

So far, we have attempted, with the help of the Catechism, to analyze “who” believes, hence, to identify the structure of the act of faith. But in so doing we have already caught sight of the outlines of the essential content of faith. In its core, Christian faith is an encounter with the living God. God is, in the proper and ultimate sense, the content of our faith. Looked at in this way, the content of faith is absolutely simple: I believe in God. But this absolute simplicity is also absolutely deep and encompassing. We can believe in God because he can touch us, because he is in us, and because he also comes to us from the outside. We can believe in him because of the one whom he has sent “Because he has ‘seen the Father,’ ” says the Catechism, referring to John 6:56, “Jesus Christ is the only one who knows him and can reveal him”. We could say that to believe is to be granted a share in Jesus’ vision. He lets us see with him in faith what he has seen.

This statement implies both the divinity of Jesus Christ and his humanity. Because Jesus is the Son, he has an unceasing vision of the Father. Because he is man, we can share this vision. Because he is both God and man at once, he is neither merely a historical person nor simply removed from all time in eternity. Rather, he is in the midst of time, always alive, always present.

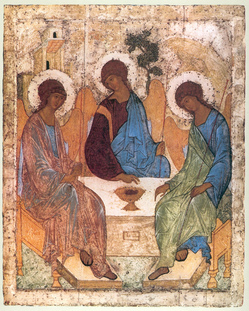

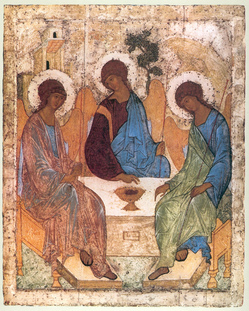

But in saying this, we also touch upon the mystery of the Trinity. The Lord becomes present to us through the Holy Spirit. Let us listen once more to the Catechism: “One cannot believe in Jesus Christ without sharing in his Spirit . . . Only God knows God completely: we believe in the Holy Spirit because he is God.” It follows from what we have said that, when we see the act of faith correctly, the single articles of faith unfold by themselves. God becomes concrete for us in Christ. This has two consequences. On the one hand, the triune mystery of God becomes discernible; on the other hand, we see that God has involved himself in history to the point that the Son has become man and now sends us the Spirit from the Father. But the Incarnation also includes the mystery of the Church, for Christ came to “gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad” [John 1:52]. The “we” of the Church is the new communion into which God draws us beyond our narrow selves [cf. John 12:32]. The Church is thus contained in the first movement of the act of faith itself. The Church is not an institution extrinsically added to faith as an organizational frame work for the common activities of believers. No, she is integral to the act of faith itself The “I believe” is always also a “We believe.” As the Catechism says, “‘I believe’ is also the Church, our mother, responding to God by faith as she teaches us to say both ‘I believe’ a ‘We believe.'” We observed just now that the analysis of the act of faith immediately displays faith’s essential content as well: faith is a response to the triune God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. We can now add that the same act of faith also embraces God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ, his theandric mystery, and thus the entirety of salvation history. It further becomes clear that the People of God, the Church as the human protagonist of salvation history, is present in the very act of faith. It would not be difficult to demonstrate in a similar fashion that the other items of belief are also explications of the one fundamental act of encountering the living God. For by its very nature, relation to God has to do with eternal life. And this relation necessarily transcends the merely human sphere. God is truly God on1y if he is the Lord of all things. And he is the Lord of all things oo1y if he is their Creator. Creation, salvation history and eternal life are thus themes that flow directly from the question of God. In addition, when we speak of God’s history with man, we also imply the issue of sin and grace. We touch upon the question of how we encounter God, hence, the question of the liturgy, of the sacraments, of prayer and morality.

But in saying this, we also touch upon the mystery of the Trinity. The Lord becomes present to us through the Holy Spirit. Let us listen once more to the Catechism: “One cannot believe in Jesus Christ without sharing in his Spirit . . . Only God knows God completely: we believe in the Holy Spirit because he is God.” It follows from what we have said that, when we see the act of faith correctly, the single articles of faith unfold by themselves. God becomes concrete for us in Christ. This has two consequences. On the one hand, the triune mystery of God becomes discernible; on the other hand, we see that God has involved himself in history to the point that the Son has become man and now sends us the Spirit from the Father. But the Incarnation also includes the mystery of the Church, for Christ came to “gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad” [John 1:52]. The “we” of the Church is the new communion into which God draws us beyond our narrow selves [cf. John 12:32]. The Church is thus contained in the first movement of the act of faith itself. The Church is not an institution extrinsically added to faith as an organizational frame work for the common activities of believers. No, she is integral to the act of faith itself The “I believe” is always also a “We believe.” As the Catechism says, “‘I believe’ is also the Church, our mother, responding to God by faith as she teaches us to say both ‘I believe’ a ‘We believe.'” We observed just now that the analysis of the act of faith immediately displays faith’s essential content as well: faith is a response to the triune God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. We can now add that the same act of faith also embraces God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ, his theandric mystery, and thus the entirety of salvation history. It further becomes clear that the People of God, the Church as the human protagonist of salvation history, is present in the very act of faith. It would not be difficult to demonstrate in a similar fashion that the other items of belief are also explications of the one fundamental act of encountering the living God. For by its very nature, relation to God has to do with eternal life. And this relation necessarily transcends the merely human sphere. God is truly God on1y if he is the Lord of all things. And he is the Lord of all things oo1y if he is their Creator. Creation, salvation history and eternal life are thus themes that flow directly from the question of God. In addition, when we speak of God’s history with man, we also imply the issue of sin and grace. We touch upon the question of how we encounter God, hence, the question of the liturgy, of the sacraments, of prayer and morality.

But I do not want to develop all of these points in detail now; my chief concern has been precisely to get a glimpse of the intrinsic unity of faith, which is not a multitude of propositions but a full and simple act whose simplicity contains the whole depth and breadth of being. He who speaks of God, speaks of the whole; he learns to discern the essential from the inessential, and he comes to know, albeit oo1y fragmentarily and “in a glass, darkly” [I Corinthians 13:12] as long as faith is faith and not yet vision, something of the inner logic and unity of all reality.

Finally, I would like to touch briefly on the question we mentioned at the beginning of our reflections. I mean the question of how we believe. Paul furnishes us with a remarkable and extremely helpful statement on this matter when he says that faith is an obedience “from the heart to the form of doctrine into which you were handed over” [Romans 6:17]. These words ultimately express the sacramental character of faith, the intrinsic connection between confession and sacrament. The Apostle says that a “form of doctrine” is an essential component of faith. We do not think up faith on our own. It does not come from us as an idea of ours but to us as a word from outside. It is, as it were, a word about the Word; we are “handed over” into this Word that reveals new paths to our reason and gives form to our life.

We are “handed over” into the Word that precedes us through an immersion in water symbolizing death. This recalls the words of Paul cited earlier: “I live, yet not I”‘; it reminds us that what takes place in the act of faith is the destruction and renewal of the self. Baptism as a symbolic death links this renewal to the death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ. To be handed over into the doctrine is to be handed over into Christ. We cannot receive his word as a theory in the same way that we learn, say, mathematical formulas or philosophical opinions. We can learn it only in accepting a share in Christ’s destiny. But we can become sharers in Christ’s destiny only where he has permanently committed himself to sharing in man’s destiny: in the Church. In the language of this Church we call this event a “sacrament”. The act of faith is unthinkable. without the sacramental component.

These remarks enable us to understand the concrete literary structure of the Catechism. To believe, as we have heard, is to be handed over into a form of doctrine. In another passage, Paul calls this form of doctrine a confession [cf. Romans 10:9]. A further aspect of the faith-event thus emerges. That is, the faith that comes to us as a word must also become a word in us, a word that is simultaneously the expression of our life. To believe is always also to confess the faith. Faith is not private but something public that concerns the community. The word of faith first enters the mind, but it cannot stay there: thought must always become word and deed again. The Catechism refers to the various kinds of confessions of faith that exist in the Church: baptismal confessions, conciliar confessions, confessions formulated by popes.

Each of these confessions has a significance of its own. But the primordial type that serves as a basis for all further developments is the baptismal creed. When we talk about catechesis, that is, initiation into the faith and adaptation of our existence to the Church’s communion of faith, we must begin with the baptismal creed. This has been true since apostolic times and therefore imposed itself as the method of the Catechism, which, in fact, unfolds the contents of faith from the baptismal creed. It thus becomes apparent how the Catechism intends to teach the faith: catechesis is catechumenate. It is not merely religious instruction but the act whereby we surrender ourselves and are received into the word of faith and communion with Jesus Christ.

Adaptation to God’s ways is an essential part of catechesis. Saint Irenaeus says a propos of this that we must accustom ourselves to God, just as in the Incarnation God accustomed himself to us men. We must accustom ourselves to God’s ways so that we can learn to bear his presence in us. Expressed in theological terms, this means that the image of God – which is what makes us capable of communion of life with him – must be freed from its encasement of dross. The tradition compares this liberation to the activity of the sculptor who chisels away at the stone bit by bit until the form that he beholds emerges into visibility.

Catechesis should always be such a process of assimilation to God. After all, we can only know a reality if there is something in us corresponding to it. Goethe, alluding to Plotinus, says that “the eye could never recognize the sun were it not itself sunlike. The cognitional process is a process of assimilation, a vital process. The “we”, the “what” and the “how” of faith belong together.

This brings to light the moral dimension of the act of faith, which includes a style of humanity we do not produce by ourselves but that we gradually learn by plunging into our baptismal existence. The sacrament of penance is one such immersion into baptism, in which God again and again acts on us and draws us back to himself Morality is an integral component of Christianity, but this morality is always part of the sacramental event of “Christianization” (Christwerdung) an event in which we are not the sole agents but are always, indeed, primarily, receivers. And this reception entails transformation.

The Catechism therefore cannot be accused of any fanciful attachment to the past when it unfolds the contents of faith using the baptismal creed of the Church of Rome, the so-called “Apostles’ Creed”. Rather, this option brings to the fore the authentic core of the act of faith and thus of catechesis as existential training in existence with God.

Equally apparent is that the Catechism is wholly structured according to the principle of the hierarchy of truths as understood by the Second Vatican Council. For, as we have seen, the creed is in the first instance a confession of faith in the triune God developed from, and bound to, the baptismal formula. All of the “truths of faith” are explications of the one truth that we discover in them. And this one truth is the pearl of great price that is worth staking our lives on: God. He alone can be the pearl for which we give everything else. Dio solo basta, he who finds God has found all things. But we can find him only because he has first sought and found us. He is the one who acts first, and for this reason faith in God is inseparable from the mystery of the Incarnation, of the Church and of the sacraments. Everything that is said in the Catechism is an unfolding of the one truth that is God himself – the “love that moves the sun and all the stars”.

[From Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger – Benedict XVI, Gospel, Catechesis, Catechism. Sidelights on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 1977, pp. 23-34. Original title: Evangelium, Katechese, Katechismus. Streiflichter auf den Katechismus der katholischen Kirche ©Verlag Neue Stadt 1995.

In our continuing catechesis on Saint Paul, we now consider his teaching on faith and works in the process of our justification. Paul insists that we are justified by faith in Christ, and not by any merit of our own. Yet he also emphasizes the relationship between faith and those works which are the fruit of the Holy Spirit’s presence and action within us. The first gift of the Spirit is love, the love of the Father and the Son poured into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Our sharing in the love of Christ leads us to live no longer for ourselves, but for him (cf. 2 Cor 5:14-15); it makes us a new creation (cf. 2 Cor 5:17) and members of his Body, the Church. Faith thus works through love (cf. Gal 5:6). Consequently, there is no contradiction between what Saint Paul teaches and what Saint James teaches regarding the relationship between justifying faith and the fruit which it bears in good works. Rather, there is a different emphasis. Redeemed by the precious blood of Christ, we are called to glorify him in our bodies (cf. 1 Cor 6:20), offering ourselves as a spiritual sacrifice pleasing to God. Justified by the gift of faith in Christ, we are called, as individuals and as a community, to treasure that gift and to let it bear rich fruit in the Spirit.

In our continuing catechesis on Saint Paul, we now consider his teaching on faith and works in the process of our justification. Paul insists that we are justified by faith in Christ, and not by any merit of our own. Yet he also emphasizes the relationship between faith and those works which are the fruit of the Holy Spirit’s presence and action within us. The first gift of the Spirit is love, the love of the Father and the Son poured into our hearts (cf. Rom 5:5). Our sharing in the love of Christ leads us to live no longer for ourselves, but for him (cf. 2 Cor 5:14-15); it makes us a new creation (cf. 2 Cor 5:17) and members of his Body, the Church. Faith thus works through love (cf. Gal 5:6). Consequently, there is no contradiction between what Saint Paul teaches and what Saint James teaches regarding the relationship between justifying faith and the fruit which it bears in good works. Rather, there is a different emphasis. Redeemed by the precious blood of Christ, we are called to glorify him in our bodies (cf. 1 Cor 6:20), offering ourselves as a spiritual sacrifice pleasing to God. Justified by the gift of faith in Christ, we are called, as individuals and as a community, to treasure that gift and to let it bear rich fruit in the Spirit.