Yesterday afternoon I was listening to a Catholic theologian giving what I thought was a fine presentation on a theology of work. He, like many Catholics, made an error that I am particularly sensitive to when it comes to Catholic Liturgy. The professor spoke of Ordinary Time in the clichéd way we often think of this period and thus distorts what we live liturgically. Ordinary Time is not distinguished by common, normal or nothing special. The Church understand the meaning of Ordinary Time as being a period of liturgical time that takes us through the ordered unfolding of the life of the Messiah in the kerygma, and orderliness of our sacramentality in word and season. Therefore, we say with liturgical precision that there is no Ordinary Time in Catholic Liturgy. There is a distinct connection of having Christmas near the shortest day of the year and Easter in the springtime. Hence, it is more accurate to say, Sundays through the Year. But that does not hold currency these days in the Church. Catholics live their life of faith different from those the evangelical Christian communities but we honor a liturgical time with those who are Orthodox and Anglican Christians.

Time has come, I believe , to come some resolution in favor of a more authentic exposition of faith in our liturgical living: Father Richard G. Cipolla, a friend and former colleague, penned this homily that was reposted on Rorate Coeli blog, “Epiphany and the Unordinariness of Liturgical Time.”

Father Cipolla’s thinking is challenging and desirous of advancing a renewal of Catholic liturgical praxis for theological reasons and not idealogical ones. The liturgical calendar is not unimportant. Quite the opposite: as the author indicates, the calendar serves the sacred Liturgy in that it helps to bear the weight of what has been given to us by the Lord and the saints. Hence, our living of liturgical time forms and informs our Christian life and how we live in the world in which find ourselves and how live with others. Do we have the shoulders to carry the lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi tradition well into the 21st century?

Father Cipolla is a priest of the Diocese of Bridgeport who came into full communion with the Catholic Church with his wife and two children; he retired from years of teaching but he a curate at St Mary’s Church, Norwalk, CT.

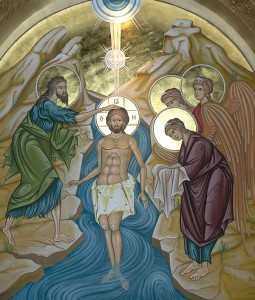

One chapter of Dom Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy is named “The Sanctification of Time”. This chapter shows how the Liturgical Calendar of the Church sanctifies time. The Liturgical Calendar does not provide merely an overlay of secular time. The Calendar is part of the recognition of the radically irruptive event of the Incarnation that changes time and space and reality forever. Of course this includes the celebrations of the feasts of the Saints, those specific celebrations of the making real of the grace of God in the lives of those who open themselves up in a total way to this grace, above all in the Blessed Virgin Mary. But the foundation of the Liturgical Calendar is the cycles that celebrate the Mysteries of the Birth, Life, Death, Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ. The Christmas cycle, which we are celebrating at this time, gives ultimate meaning to the secular, physical time when the days are becoming longer, a bit more light each day. In the Christmas cycle we celebrate the coming into the world of the Light that shines in the darkness. We celebrate the making flesh of God in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the birth of her child whose name is Jesus—he who comes to save. The climax of this cycle has always been the Epiphany, a feast older than Christmas, a feast that celebrates the fact that the event and the person of the Incarnation embraces not only time and space but embraces all the peoples of the world. And the feast of the Epiphany proclaims in its three-fold way the answer to the seminal question asked in the Gospels: who is this man Jesus? He is the one who is worshipped as God. He is the one who is the Son of God in whom his Father is well pleased. He is the one who changes water into wine, for he is the Lord of creation itself.

One chapter of Dom Gregory Dix’s The Shape of the Liturgy is named “The Sanctification of Time”. This chapter shows how the Liturgical Calendar of the Church sanctifies time. The Liturgical Calendar does not provide merely an overlay of secular time. The Calendar is part of the recognition of the radically irruptive event of the Incarnation that changes time and space and reality forever. Of course this includes the celebrations of the feasts of the Saints, those specific celebrations of the making real of the grace of God in the lives of those who open themselves up in a total way to this grace, above all in the Blessed Virgin Mary. But the foundation of the Liturgical Calendar is the cycles that celebrate the Mysteries of the Birth, Life, Death, Resurrection and Ascension of the Lord Jesus Christ. The Christmas cycle, which we are celebrating at this time, gives ultimate meaning to the secular, physical time when the days are becoming longer, a bit more light each day. In the Christmas cycle we celebrate the coming into the world of the Light that shines in the darkness. We celebrate the making flesh of God in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the birth of her child whose name is Jesus—he who comes to save. The climax of this cycle has always been the Epiphany, a feast older than Christmas, a feast that celebrates the fact that the event and the person of the Incarnation embraces not only time and space but embraces all the peoples of the world. And the feast of the Epiphany proclaims in its three-fold way the answer to the seminal question asked in the Gospels: who is this man Jesus? He is the one who is worshipped as God. He is the one who is the Son of God in whom his Father is well pleased. He is the one who changes water into wine, for he is the Lord of creation itself.

One of the saddest and most deleterious effects of the changes in the structure and content of the Liturgical Calendar in the post-Conciliar reform is the lack of understanding of the sanctification of time by the feasts and fasts of the Church. The introduction, at least in English, of the term, “ordinary time”, contradicts the fact that after the Incarnation there is no “ordinary” time. There is only the extraordinary time that has been brought into being by the insertion of the dagger of the Incarnation into ordinary time. Now we know that the term “ordinary time” is a poor translation of the Latin term for “in course”. But even this does not take away from the fact of the impoverishment of the Liturgical Calendar that has been effected by taking away the Sundays after the Epiphany and the Sundays after Pentecost. The traditional way of naming these Sundays understood that these two feasts, Epiphany and Pentecost, are the climaxes of the Christmas and Easter seasons, the seasons that celebrate the event and meaning of, respectively, the Birth, and the Death and Resurrection of Christ, and therefore these feasts become the touchstone, the source of reality of the Sundays of the Church Year.

One of the marks of the Novus Ordo form and its calendar that is striking evidence of its incapacity to bear the weight of the Catholic Tradition is its source in a committee. Something organic has nothing to do with a liturgical commission or consilium or committee. As soon as one thinks that the Liturgy can be treated as a mere text to be updated, the possibility of worship is severely lessened. That is what the Protestant reformers thought. They rewrote their Mass texts to suit their ideology. And, for the most part, liturgical worship died in those churches. And where it did survive, as in Anglicanism, it did so thanks to both an innate conservatism and finally to a revival in the 19th century of a more Catholic understanding of the Eucharist.

The whole question of what happened and how it happened with respect to the Novus Ordo rite vis a vis the imposition of a particular ideology based on the scholarship du jour, and the personal predilections of those in charge of the post-Conciliar reforms, is a conversation that has not been allowed to happen by those “in charge” of such things in Rome. There is no doubt that such a conversation will be had and must be had, for the good of the Church. But that will come inevitably in time.

But surely, the question of the Liturgical Calendar and the mistakes made in its Novus Ordo formulation can be discussed now. The imposition of a pre-conceived “orderliness” that demands that the Christmas season end with the feast of the Epiphany and with no time for the Octave to reflect on this seminal feast must be revisited. This is compounded when the feast of the Epiphany is celebrated on a Sunday. The irony here is that one of the battle cries of the reform of the Calendar was the restoration of the primacy of Sunday in the Liturgical Year. Surely we can now see the foolishness of the possibility of celebrating the Epiphany as early as on January 2, four full days before the actual feast that is celebrated in those parts of the Western Church still on January 6 and celebrated on that day by our Orthodox brethren throughout the world with the solemnity it deserves. It is foolish as well to celebrate this feast after January 6, as if it is irrelevant to the sanctification of time when any feast is celebrated, for the guiding principle in this reform is the convenience of the people: it is more convenient for the people to celebrate the Epiphany on Sunday rather than the interruption of having to go to Mass on a weekday. But it is precisely the interruption that is the point. The irruption of the Incarnation demands such an interruption, demands such an “inconvenience”, for it is a reminder of the sanctification of time itself to those of us who forget that time and space and the world and our lives and our future have been radically changed by the Incarnation of God in Jesus Christ.

It may be too much to hope that a real conversation about the Liturgical Calendar of the Novus Ordo form will take place soon. But surely we can hope that our Bishops will soon see the deleterious effect of moving the Epiphany and other major feasts of our Lord to Sunday and will put an end to this practice. For this, let us pray.

Asked why is Epiphany/Theophany important is answered only by looking at the sacred Liturgy? This feast is one of the oldest of the Christians even predating the December 25th observance of the Lord’s Nativity. This is a good exercise in doing liturgical theology: reflecting on the texts of the Liturgy as a way of understanding why do and believe what we do. This is theologia prima.

Asked why is Epiphany/Theophany important is answered only by looking at the sacred Liturgy? This feast is one of the oldest of the Christians even predating the December 25th observance of the Lord’s Nativity. This is a good exercise in doing liturgical theology: reflecting on the texts of the Liturgy as a way of understanding why do and believe what we do. This is theologia prima.