The annual papal address to the laity, sisters, brothers, priests, bishops and cardinals (the Roman Curia) who serve the Church in the various offices at the Holy See and Vatican that make the Pope’s ministry possible. It is long, but it is breath-taking. Read, prayer, and change accordingly.

Address by the Holy Father on the occasion of Christmas greetings to the Roman Curia

20 December 2010

It gives me great pleasure to be here with you, dear Members of the College of Cardinals and Representatives of the Roman Curia and the Governatorato, for this traditional gathering. I extend a cordial greeting to each one of you, beginning with Cardinal Angelo Solano, whom I thank for his sentiments of devotion and communion and for the warm good wishes that he expressed to me on behalf of all of you. Prope est jam Dominos, venite, adoremus! As one family let us contemplate the mystery of Emmanuel, God-with-us, as the Cardinal Dean has said. I gladly reciprocate his good wishes and I would like to thank all of you most sincerely, including the Papal Representatives all over the world, for the able and generous contribution that each of you makes to the Vicar of Christ and to the Church.

Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni. Repeatedly during the season of Advent the Church’s liturgy prays in these or similar words. They are invocations that were probably formulated as the Roman Empire was in decline. The disintegration of the key principles of law and of the fundamental moral attitudes underpinning them burst open the dams which until that time had protected peaceful coexistence among peoples. The sun was setting over an entire world. Frequent natural disasters further increased this sense of insecurity. There was no power in sight that could put a stop to this decline. All the more insistent, then, was the invocation of the power of God: the plea that he might come and protect his people from all these threats.

Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni. Today too, we have many reasons to associate ourselves with this Advent prayer of the Church. For all its new hopes and possibilities, our world is at the same time troubled by the sense that moral consensus is collapsing, consensus without which juridical and political structures cannot function. Consequently the forces mobilized for the defense of such structures seem doomed to failure.+Excita – the prayer recalls the cry addressed to the Lord who was sleeping in the disciples’ storm-tossed boat as it was close to sinking. When his powerful word had calmed the storm, he rebuked the disciples for their little faith (cf. Mt 8:26 et par.). He wanted to say: it was your faith that was sleeping. He will say the same thing to us. Our faith too is often asleep. Let us ask him, then, to wake us from the sleep of a faith grown tired, and to restore to that faith the power to move mountains – that is, to order justly the affairs of the world.

Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni: amid the great tribulations to which we have been exposed during the past year, this Advent prayer has frequently been in my mind and on my lips. We had begun the Year for Priests with great joy and, thank God, we were also able to conclude it with great gratitude, despite the fact that it unfolded so differently from the way we had expected. Among us priests and among the lay faithful, especially the young, there was a renewed awareness of what a great gift the Lord has entrusted to us in the priesthood of the Catholic Church. We realized afresh how beautiful it is that human beings are fully authorized to pronounce in God’s name the word of forgiveness, and are thus able to change the world, to change life; we realized how beautiful it is that human beings may utter the words of consecration, through which the Lord draws a part of the world into himself, and so transforms it at one point in its very substance; we realized how beautiful it is to be able, with the Lord’s strength, to be close to people in their joys and sufferings, in the important moments of their lives and in their dark times; how beautiful it is to have as one’s life task not this or that, but simply human life itself – helping people to open themselves to God and to live from God. We were all the more dismayed, then, when in this year of all years and to a degree we could not have imagined, we came to know of abuse of minors committed by priests who twist the sacrament into its antithesis, and under the mantle of the sacred profoundly wound human persons in their childhood, damaging them for a whole lifetime.

In this context, a vision of Saint Hildegard of Bingen came to my mind, a vision which describes in a shocking way what we have lived through this past year. “In the year of our Lord’s incarnation 1170, I had been lying on my sick-bed for a long time when, fully conscious in body and in mind, I had a vision of a woman of such beauty that the human mind is unable to comprehend. She stretched in height from earth to heaven. Her face shone with exceeding brightness and her gaze was fixed on heaven. She was dressed in a dazzling robe of white silk and draped in a cloak, adorned with stones of great price. On her feet she wore shoes of onyx. But her face was stained with dust, her robe was ripped down the right side, her cloak had lost its sheen of beauty and her shoes had been blackened. And she herself, in a voice loud with sorrow, was calling to the heights of heaven, saying, ‘Hear, heaven, how my face is sullied; mourn, earth, that my robe is torn; tremble, abyss, because my shoes are blackened!’

And she continued: ‘I lay hidden in the heart of the Father until the Son of Man, who was conceived and born in virginity, poured out his blood. With that same blood as his dowry, he made me his betrothed.

For my Bridegroom’s wounds remain fresh and open as long as the wounds of men’s sins continue to gape. And Christ’s wounds remain open because of the sins of priests. They tear my robe, since they are violators of the Law, the Gospel and their own priesthood; they darken my cloak by neglecting, in every way, the precepts which they are meant to uphold; my shoes too are blackened, since priests do not keep to the straight paths of justice, which are hard and rugged, or set good examples to those beneath them. Nevertheless, in some of them I find the splendour of truth.

And I heard a voice from heaven which said: ‘This image represents the Church. For this reason, O you who see all this and who listen to the word of lament, proclaim it to the priests who are destined to offer guidance and instruction to God’s people and to whom, as to the apostles, it was said: go into all the world and preach the Gospel to the whole creation’ (Mk 16:15)” (Letter to Werner von Kirchheim and his Priestly Community: PL 197, 269ff.).

In the vision of Saint Hildegard, the face of the Church is stained with dust, and this is how we have seen it. Her garment is torn – by the sins of priests. The way she saw and expressed it is the way we have experienced it this year. We must accept this humiliation as an exhortation to truth and a call to renewal. Only the truth saves. We must ask ourselves what we can do to repair as much as possible the injustice that has occurred. We must ask ourselves what was wrong in our proclamation, in our whole way of living the Christian life, to allow such a thing to happen. We must discover a new resoluteness in faith and in doing good. We must be capable of doing penance. We must be determined to make every possible effort in priestly formation to prevent anything of the kind from happening again. This is also the moment to offer heartfelt thanks to all those who work to help victims and to restore their trust in the Church, their capacity to believe her message. In my meetings with victims of this sin, I have also always found people who, with great dedication, stand alongside those who suffer and have been damaged. This is also the occasion to thank the many good priests who act as channels of the Lord’s goodness in humility and fidelity and, amid the devastations, bear witness to the unforfeited beauty of the priesthood.

We are well aware of the particular gravity of this sin committed by priests and of our corresponding responsibility. But neither can we remain silent regarding the context of these times in which these events have come to light. There is a market in child pornography that seems in some way to be considered more and more normal by society. The psychological destruction of children, in which human persons are reduced to articles of merchandise, is a terrifying sign of the times. From Bishops of developing countries I hear again and again how sexual tourism threatens an entire generation and damages its freedom and its human dignity. The Book of Revelation includes among the great sins of Babylon – the symbol of the world’s great irreligious cities – the fact that it trades with bodies and souls and treats them as commodities (cf. Rev 18:13). In this context, the problem of drugs also rears its head, and with increasing force extends its octopus tentacles around the entire world – an eloquent expression of the tyranny of mammon which perverts mankind. No pleasure is ever enough, and the excess of deceiving intoxication becomes a violence that tears whole regions apart – and all this in the name of a fatal misunderstanding of freedom which actually undermines man’s freedom and ultimately destroys it.

In order to resist these forces, we must turn our attention to their ideological foundations. In the 1970s, paedophilia was theorized as something fully in conformity with man and even with children. This, however, was part of a fundamental perversion of the concept of ethos. It was maintained – even within the realm of Catholic theology – that there is no such thing as evil in itself or good in itself. There is only a “better than” and a “worse than”. Nothing is good or bad in itself. Everything depends on the circumstances and on the end in view. Anything can be good or also bad, depending upon purposes and circumstances. Morality is replaced by a calculus of consequences, and in the process it ceases to exist. The effects of such theories are evident today. Against them, Pope John Paul II, in his 1993 Encyclical Letter Veritatis Splendor, indicated with prophetic force in the great rational tradition of Christian ethos the essential and permanent foundations of moral action. Today, attention must be focussed anew on this text as a path in the formation of conscience. It is our responsibility to make these criteria audible and intelligible once more for people today as paths of true humanity, in the context of our paramount concern for mankind.

As my second point, I should like to say a word about the Synod of the Churches of the Middle East. This began with my journey to Cyprus, where I was able to consign the Instrumentum Laboris of the Synod to the Bishops of those countries who were assembled there. The hospitality of the Orthodox Church was unforgettable, and we experienced it with great gratitude. Even if full communion is not yet granted to us, we have nevertheless established with joy that the basic form of the ancient Church unites us profoundly with one another: the sacramental office of Bishops as the bearer of apostolic tradition, the reading of Scripture according to the hermeneutic of the Regula fidei, the understanding of Scripture in its manifold unity centred on Christ, developed under divine inspiration, and finally, our faith in the central place of the Eucharist in the Church’s life. Thus we experienced a living encounter with the riches of the rites of the ancient Church that are also found within the Catholic Church. We celebrated the liturgy with Maronites and with Melchites, we celebrated in the Latin rite, we experienced moments of ecumenical prayer with the Orthodox, and we witnessed impressive manifestations of the rich Christian culture of the Christian East. But we also saw the problem of the divided country. The wrongs and the deep wounds of the past were all too evident, but so too was the desire for the peace and communion that had existed before. Everyone knows that violence does not bring progress – indeed, it gave rise to the present situation. Only in a spirit of compromise and mutual understanding can unity be re-established. To prepare the people for this attitude of peace is an essential task of pastoral ministry.

During the Synod itself, our gaze was extended over the whole of the Middle East, where the followers of different religions – as well as a variety of traditions and distinct rites – live together. As far as Christians are concerned, there are Pre-Chalcedonian as well as Chalcedonian churches; there are churches in communion with Rome and others that are outside that communion; in both cases, multiple rites exist alongside one another. In the turmoil of recent years, the tradition of peaceful coexistence has been shattered and tensions and divisions have grown, with the result that we witness with increasing alarm acts of violence in which there is no longer any respect for what the other holds sacred, in which on the contrary the most elementary rules of humanity collapse. In the present situation, Christians are the most oppressed and tormented minority. For centuries they lived peacefully together with their Jewish and Muslim neighbours. During the Synod we listened to wise words from the Counsellor of the Mufti of the Republic of Lebanon against acts of violence targeting Christians. He said: when Christians are wounded, we ourselves are wounded.

Unfortunately, though, this and similar voices of reason, for which we are profoundly grateful, are too weak. Here too we come up against an unholy alliance between greed for profit and ideological blindness. On the basis of the spirit of faith and its rationality, the Synod developed a grand concept of dialogue, forgiveness and mutual acceptance, a concept that we now want to proclaim to the world. The human being is one, and humanity is one. Whatever damage is done to another in any one place, ends up by damaging everyone. Thus the words and ideas of the Synod must be a clarion call, addressed to all people with political or religious responsibility, to put a stop to Christianophobia; to rise up in defence of refugees and all who are suffering, and to revitalize the spirit of reconciliation. In the final analysis, healing can only come from deep faith in God’s reconciling love. Strengthening this faith, nourishing it and causing it to shine forth is the Church’s principal task at this hour.+I would willingly speak in some detail of my unforgettable journey to the United Kingdom, but I will limit myself to two points that are connected with the theme of the responsibility of Christians at this time and with the Church’s task to proclaim the Gospel. My thoughts go first of all to the encounter with the world of culture in Westminster Hall, an encounter in which awareness of shared responsibility at this moment in history created great attention which, in the final analysis, was directed to the question of truth and faith itself. It was evident to all that the Church has to make her own contribution to this debate. Alexis de Tocqueville, in his day, observed that democracy in America had become possible and had worked because there existed a fundamental moral consensus which, transcending individual denominations, united everyone. Only if there is such a consensus on the essentials can constitutions and law function. This fundamental consensus derived from the Christian heritage is at risk wherever its place, the place of moral reasoning, is taken by the purely instrumental rationality of which I spoke earlier. In reality, this makes reason blind to what is essential. To resist this eclipse of reason and to preserve its capacity for seeing the essential, for seeing God and man, for seeing what is good and what is true, is the common interest that must unite all people of good will. The very future of the world is at stake.

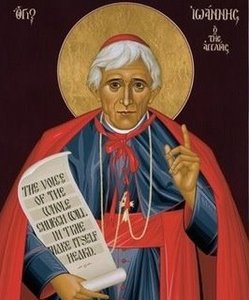

Finally I should like to recall once more the beatification of Cardinal John Henry Newman. Why was he beatified? What does he have to say to us? Many responses could be given to these questions, which were explored in the context of the beatification. I would like to highlight just two aspects which belong together and which, in the final analysis, express the same thing. The first is that we must learn from Newman’s three conversions, because they were steps along a spiritual path that concerns us all. Here I would like to emphasize just the first conversion: to faith in the living God. Until that moment, Newman thought like the average men of his time and indeed like the average men of today, who do not simply exclude the existence of God, but consider it as something uncertain, something with no essential role to play in their lives. What appeared genuinely real to him, as to the men of his and our day, is the empirical, matter that can be grasped. This is the “reality” according to which one finds one’s bearings. The “real” is what can be grasped, it is the things that can be calculated and taken in one’s hand. In his conversion, Newman recognized that it is exactly the other way round: that God and the soul, man’s spiritual identity, constitute what is genuinely real, what counts. These are much more real than objects that can be grasped. This conversion was a Copernican revolution. What had previously seemed unreal and secondary was now revealed to be the genuinely decisive element. Where such a conversion takes place, it is not just a person’s theory that changes: the fundamental shape of life changes. We are all in constant need of such conversion: then we are on the right path.

The driving force that impelled Newman along the path of conversion was conscience. But what does this mean? In modern thinking, the word “conscience” signifies that for moral and religious questions, it is the subjective dimension, the individual, that constitutes the final authority for decision. The world is divided into the realms of the objective and the subjective. To the objective realm belong things that can be calculated and verified by experiment. Religion and morals fall outside the scope of these methods and are therefore considered to lie within the subjective realm. Here, it is said, there are in the final analysis no objective criteria. The ultimate instance that can decide here is therefore the subject alone, and precisely this is what the word “conscience” expresses: in this realm only the individual, with his intuitions and experiences, can decide. Newman’s understanding of conscience is diametrically opposed to this. For him, “conscience” means man’s capacity for truth: the capacity to recognize precisely in the decision-making areas of his life – religion and morals – a truth, the truth. At the same time, conscience – man’s capacity to recognize truth – thereby imposes on him the obligation to set out along the path towards truth, to seek it and to submit to it wherever he finds it.

Conscience is both capacity for truth and obedience to the truth which manifests itself to anyone who seeks it with an open heart. The path of Newman’s conversions is a path of conscience – not a path of self-asserting subjectivity but, on the contrary, a path of obedience to the truth that was gradually opening up to him. His third conversion, to Catholicism, required him to give up almost everything that was dear and precious to him: possessions, profession, academic rank, family ties and many friends. The sacrifice demanded of him by obedience to the truth, by his conscience, went further still. Newman had always been aware of having a mission for England. But in the Catholic theology of his time, his voice could hardly make itself heard. It was too foreign in the context of the prevailing form of theological thought and devotion. In January 1863 he wrote in his diary these distressing words: “As a Protestant, I felt my religion dreary, but not my life – but, as a Catholic, my life dreary, not my religion”. He had not yet arrived at the hour when he would be an influential figure. In the humility and darkness of obedience, he had to wait until his message was taken up and understood. In support of the claim that Newman’s concept of conscience matched the modern subjective understanding, people often quote a letter in which he said – should he have to propose a toast – that he would drink first to conscience and then to the Pope. But in this statement, “conscience” does not signify the ultimately binding quality of subjective intuition. It is an expression of the accessibility and the binding force of truth: on this its primacy is based. The second toast can be dedicated to the Pope because it is his task to demand obedience to the truth.

I must refrain from speaking of my remarkable journeys to Malta, Portugal and Spain. In these it once again became evident that the faith is not a thing of the past, but an encounter with the God who lives and acts now. He challenges us and he opposes our indolence, but precisely in this way he opens the path towards true joy.

Excita, Domine, potentiam tuam, et veni. We set out from this plea for the presence of God’s power in our time and from the experience of his apparent absence. If we keep our eyes open as we look back over the year that is coming to an end, we can see clearly that God’s power and goodness are also present today in many different ways. So we all have reason to thank him. Along with thanks to the Lord I renew my thanks to all my co-workers. May God grant to all of us a holy Christmas and may he accompany us with his blessings in the coming year.

I entrust these prayerful sentiments to the intercession of the Holy Virgin, Mother of the Redeemer, and I impart to all of you and to the great family of the Roman Curia a heartfelt Apostolic Blessing. Happy Christmas!