“Come, let us climb the LORD’s mountain, to the house of the God of Jacob, that he may instruct us in his ways, and we may walk in his paths” (Isaiah).

“Come, let us climb the LORD’s mountain, to the house of the God of Jacob, that he may instruct us in his ways, and we may walk in his paths” (Isaiah).

The Church moves her children into a liturgical year today with the beginning of Advent, a time of preparation for nativity of Jesus, a time which opens a new door that opens into a new year of grace and witness to the Divine Presence.

Our sense of sight is slightly altered with the vestments of the priest and deacon changed to purple, and the introduction of the wreathe to help us keep time. There is no Gloria and perhaps the choirmaster will sing some of the ancient chants.

The color purple ought not to be lost on us. Our King wears a crown of thorns; our King offers himself in sacrifice on the Cross for love of all humanity; our King, not regal and aloof is the servant and friend of the poor; our King is educates our freedom to wholeness and the true gift of being given a humanity that’s fully realized in Him. The use of the color purple reminds us that Jesus is king and that there is nothing ordinary about Him: Jesus is the Word made flesh, the Eternal Word of God who entered, and continues to enter, into human history. The priest images the Lord in our context. Lastly, I would recall that purple is a time of penance.

Many liturgists, often at the parish level, step away from Advent being a penitential season. But they are offering a false teaching. It is true that the penitential character of Advent is not same as Lent. It is, however, a period of time of preparation which is marked by elements of conversion, instruction and walking anew in the paths given to us by the Lord. I would reference the scripture readings given for Mass for the First Sunday of Advent. A sentence from the first reading is given above. There is also this line from Romans where Saint Paul and the Church calls us to change: “…it is the hour now for you to awake from sleep. For our salvation is nearer now than when we first believed; the night is advanced, the day is at hand. Let us then throw off the works of darkness and put on the armor of light…”

In addition to Paul’s exhortation to be awake, in several other places in scripture the holy authors speak of staying awake, of being less sleepy in the face of the coming of the Lord. This theme gets carried over into the season of Advent as a time of keeping watch with and for Jesus Christ.

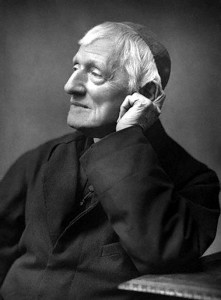

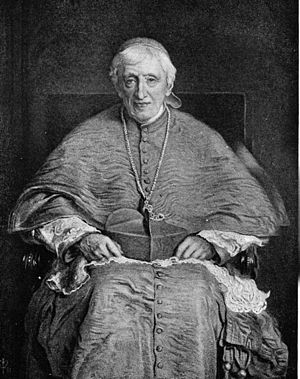

Blessed John Henry Newman has something to say to us about watching, and notice very carefully his argument:

Now I consider this word watching, first used by our Lord, then by the favoured Disciple, then by the two great Apostles, Peter and Paul, is a remarkable word, remarkable because the idea is not so obvious as might appear at first sight, and next because they all inculcate it. We are not simply to believe, but to watch; not simply to love, but to watch; not simply to obey, but to watch; to watch for what? for that great event, Christ’s coming. Whether then we consider what is the obvious meaning of the word, or the Object towards which it directs us, we seem to see a special duty enjoined on us, such as does not naturally come into our minds. Most of us have a general idea what is meant by believing, fearing, loving, and obeying; but perhaps we do not contemplate or apprehend what is meant by watching.

And I conceive it is one of the main points, which, in a practical way, will be found to separate the true and perfect servants of God from the multitude called Christians; from those who are, I do not say false and reprobate, but who are such that we cannot speak much about them, nor can form any notion what will become of them. And in saying this, do not understand me as saying, which I do not, that we can tell for certain who are the perfect, and who the double-minded or incomplete Christians; or that those who discourse and insist upon these subjects are necessarily on the right side of the line. I am but speaking of two characters, the true and consistent character, and the inconsistent; and these I say will be found in no slight degree discriminated and distinguished by this one mark,—true Christians, whoever they are, watch, and inconsistent Christians do not. Now what is watching?

I conceive it may be explained as follows:—Do you know the feeling in matters of this life, of expecting a friend, expecting him to come, and he delays? Do you know what it is to be in unpleasant company, and to wish for the time to pass away, and the hour strike when you may be at liberty? Do you know what it is to be in anxiety lest something should happen which may happen or may not, or to be in suspense about some important event, which makes your heart beat when you are reminded of it, and of which you think the first thing in the morning? Do you know what it is to have a friend in a distant country, to expect news of him, and to wonder from day to day what he is now doing, and whether he is well? Do you know what it is so to live upon a person who is present with you, that your eyes follow his, that you read his soul, that you see all its changes in his countenance, that you anticipate his wishes, that you smile in his smile, and are sad in his sadness, and are downcast when he is vexed, and rejoice in his successes? To watch for Christ is a feeling such as all these; as far as feelings of this world are fit to shadow out those of another.

He watches for Christ who has a sensitive, eager, apprehensive mind; who is awake, alive, quick-sighted, zealous in seeking and honouring Him; who looks out for Him in all that happens, and who would not be surprised, who would not be over-agitated or overwhelmed, if he found that He was coming at once.

And he watches with Christ, who, while he looks on to the future, looks back on the past, and does not so contemplate what his Saviour has purchased for him, as to forget what He has suffered for him. He watches with Christ, who ever commemorates and renews in his own person Christ’s Cross and Agony, and gladly takes up that mantle of affliction which Christ wore here, and left behind Him when he ascended. And hence in the Epistles, often as the inspired writers show their desire for His second coming, as often do they show their memory of His first, and never lose sight of His Crucifixion in His Resurrection. Thus if St. Paul reminds the Romans that they “wait for the redemption of the body” at the Last Day, he also says, “If so be that we suffer with Him, that we may be also glorified together.” If he speaks to the Corinthians of “waiting for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ,” he also speaks of “always bearing about in the body the dying of the Lord Jesus, that the life also of Jesus might be made manifest in our body.” If to the Philippians of “the power of His resurrection,” he adds at once “and the fellowship of His sufferings, being made conformable unto His death.” If he consoles the Colossians with the hope “when Christ shall appear,” of their “appearing with Him in glory,” he has already declared that he “fills up that which remains of the afflictions of Christ in his flesh for His body’s sake, which is the Church.” [Rom. viii. 17-28. 1 Cor. i. 7. 2 Cor. iv. 10. Phil. iii. 10. Col. iii. 4; i. 24.] Thus the thought of what Christ is, must not obliterate from the mind the thought of what He was; and faith is always sorrowing with Him while it rejoices. And the same union of opposite thoughts is impressed on us in Holy Communion, in which we see Christ’s death and resurrection together, at one and the same time; we commemorate the one, we rejoice in the other; we make an offering, and we gain a blessing.

This then is to watch; to be detached from what is present, and to live in what is unseen; to live in the thought of Christ as He came once, and as He will come again; to desire His second coming, from our affectionate and grateful remembrance of His first. And this it is, in which we shall find that men in general are wanting. They are indeed without faith and love also; but at least they profess to have these graces, nor is it easy to convince them that they have not. For they consider they have faith, if they do but own that the Bible came from God, or that they trust wholly in Christ for salvation; and they consider they have love if they obey some of the most obvious of God’s commandments. Love and faith they think they have; but surely they do not even fancy that they watch. What is meant by watching, and how it is a duty, they have no definite idea; and thus it accidentally happens that watching is a suitable test of a Christian, in that it is that particular property of faith and love, which, essential as it is, men of this world do not even profess; that particular property, which is the life or energy of faith and love, the way in which faith and love, if genuine, show themselves.

Parochial and Plain Sermons, vol. 4, Sermon 22

Today’s the feast of the great Englishman, St. John Henry Newman.

Today’s the feast of the great Englishman, St. John Henry Newman.