One of my liturgical heroes is the late Father Alexander Schmemann. His work really hits home because of his concern for encountering the Savior of humanity. Father Alexander died 30 years ago today. Eternal memory.

One of my liturgical heroes is the late Father Alexander Schmemann. His work really hits home because of his concern for encountering the Savior of humanity. Father Alexander died 30 years ago today. Eternal memory.

A brief biography of Father Alexander Schmemann can be read here; I would also suggest doing some personal reading on liturgical theology through the eyes of Schmemann.

A friend of sent me these 2 reflections today which I think is quite helpful in understanding the personality of this fine priest and theologian.

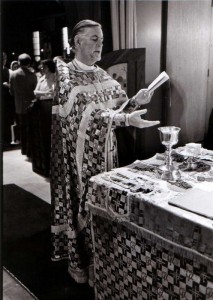

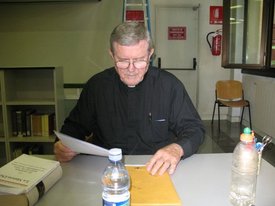

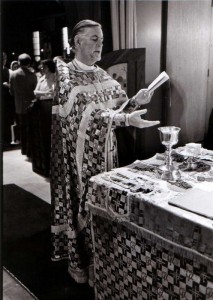

This is a photograph I like of Fr Alexander Schmemann one of the makers of the Eastern Orthodox world today and who was my teacher and who died 30 years ago today. and here are two items which I think are important and interesting to anyone at all as he was a maker also of our world in general although in a somewhat hidden place at a small seminary in the hudson valley. first an appreciation by Fr. Alexis Vinogradov, and second a memoir by his daughter Masha.

(1)… One “YES” December 13, 2013

“Jesus Christ…having abolished in His flesh the enmity, that is, the law of commandments contained in the ordinances, created in himself one new man from the two, thus making peace.” (paraphrase of part of last Sunday’s epistle, Ephesians 2:15)

A brief thirty years have passed since the death of Fr Alexander Schmemann—a lifetime for a younger generation of intelligent church leaders and a mere moment for those who personally knew him. I am among those older people who can easily claim that Fr Alexander single-handedly and very personally shaped our theology, and therefore influenced a great part of our lives. In fact, his influence on my generation was so profound that we find ourselves struggling to incorporate his vision often troubled by a very different approach that occupies religion today. Fr Schmemann’s own published Journals testify to his personal struggle with the divergent visions of the Church.

What largely marks Fr Alexander’s vast legacy of lectures, sermons, and essays was his caution against what he called reductions, that is, the tendency to obsess over isolated issues, and consequently to idolize them, to turn them into a cause and a source of division and conflict. To avoid such reductions, he constantly urged us not to be tempted to “solve” the Church’s deficiencies or to idealize some bygone time or era when things were perfect. Rather, he encouraged us to look deeper at the dimension of the Kingdom of God already permeating human life. The Church’s role is to bring us into a closer union with that experience of the Kingdom, but the Church as such is NOT a substitute for that experience, rather, She reveals that experience to us. Christ came to restore and bring God’s world to the Father, and not to establish a self-absorbed cult.

Fr Alexander warned against religious activism, teaching instead a wholesome engagement with the world through mission. But this idea of mission was not the conventional notion we have today of multiplying converts in order to fill the pews. For him, this mission did not consist in theological controversies or religious activity, but the bringing of one’s own transfigured life into daily engagement with the neighbor, the one in front of me at this moment. The man who shares Fr Alexander’s day of death, Herman of Alaska, was a simple monk leading a secluded life in the wilderness, and yet his influence was so vast that he became America’s first recognized saint.

Just as the Kingdom of God cannot be reduced to an easy definition, or to religious activism so too, the persons who are beloved by God, cannot be reduced to their functions or their virtues and vices. It is notable that while Fr Alexander could be the harshest critic of human behavior, he maintained the deepest respect for the individual person, always knowing that this particular person is the object of God’s love and salvation. We live in a time of constant anxiety and therefore of personal recrimination—we often need to blame someone for the way we feel. It is hard for us to understand that we are on our journey together, and that only by continuing together to offer our broken lives in the Eucharistic gathering, can we overcome the alienation we experience, and the hostility that marks our times even and especially within the Christian family.

In the culture that formed Fr Alexander it was inconceivable for Orthodox people to be solely concerned with the development and future of their own Orthodoxy. While he was convinced of the fullness of Orthodox life and teaching, he understood that Orthodoxy, and its experience of that very Kingdom which he preached, was the source from which one reaches always outside oneself. That explains his engagement with others on the ecumenical stage. No doubt he would have continued to express some bitterness over many of the externals that define Orthodox today. I am thinking specifically about the interest in certain circles of the restoration of old country architecture, the fascination with forms of apparel and conduct, preoccupation with rubrics, and an assault on cultural norms and morality—all of which suggests the preservation of a romantic Orthodox “Age” to counter a perceived secularism. If the world is indeed gone secular, one has to wonder about the sudden and growing appeal of Pope Francis who preaches a very humane restoration of human relationships. Why is his spirituality so attractive to a younger generation that supposedly has no interest in the Church? Doesn’t one have to ask what digressions in religion drove that generation away in the first place?

Just as we see the restoration beginning today with Pope Francis on a one to one personal basis, so too, for Fr Alexander, theological engagement and progress is only possible among individual persons willing to be actively engaged with one another, not on the level of polemics and ideas and conferences, but in dialogue and action rooted in love and in the joyful exuberance that Christ’s victory over death has come. For me, the most fascinating aspect of his personality was his ability to confront any deviation from truth directly in a good solid debate, without ever reducing his “opponent” to an object, or a hurdle to overcome, an enemy to conquer—but rather seeing that person as a beloved soul that he hoped both to learn from and to convince with truth and patience.

My friend Deacon Peter Danilchik likes to describe how he had once asked Fr Schmemann whether he should confront another cleric whose actions he deplored. Fr Schmemann answered: “Of course, but only if you know that your motivation is borne out of love!” In Father’s published journals it is especially clear that such confrontations were the order of his professional life, not excluding the hallowed halls of his own beloved Seminary. No parish can claim that such conflicts are not present in their own daily lives—it is simply the human condition. But the antidotes are not far away, for this split—these conflicts—are first of all inside each of us. If I would but only see that my anger against a neighbor has first taken root by a division within myself; and that when I confront my own internal division, I can only then properly confront in love my neighbor. Here lies the essence of St.Paul’s words to the Ephesians in the heading above. The famous “dividing wall of hostility between the two” which Christ overcomes, is none other than the hostility working in my own soul, the war between the Old and New Adam within me.

If we are to discover the particularity of Fr Alexander’s teaching today, it does not lie in some complex theological formulations, in some innovative theology that he developed. Rather, his gift is the real incarnation of Christian truth in his own person. When Veselin Kesich said at Fr Schmemann’s funeral that “he was a free man in Christ, a man filled with humor and stories”, he defined once and for all the “what” of Fr Schmemann. The “who” will always be an irreducible mystery, but his “what” is exactly this freedom and lightness of life. And for him this was the conviction that Christ has come and death is no more.

I am personally convinced that is the reason that Father Alexander is not only NOT dead, but continues to grow and flourish in the Church’s consciousness day by day. I believe that his legacy is only now beginning to take root, that having lived a brief while “without” him, so to speak, the Church is beginning again to live with him. To me it seems ironic that this “free man in Christ”, who eschewed all forms of outward piety, who smoked Gitanes (which may have proved his physical demise) and loved a good beefsteak, is headed toward the road of sanctity, or more accurately perhaps, has by his honest and open life already shown us what a contemporary true and saintly human being looks like! He has shown us that we are all indeed potential “saints” bound by our desire to offer our broken and healed selves to the God who came, and is coming in this season of Advent light, to be one with us, and raise us to Himself!

by Alexis Vinogradov 12.13.13

(2) MY FATHER

Alexander Schmemann was my father. And it is as my father that I will share some memories with you.

My father was not directly involved in our upbringing. He was always there, but it is my mother who really ran the household and dealt with the day-to-day responsibilities of child rearing. However, she did this really well and had my father’s total support every step of the way.

Today I would like to share snapshots of my father as they appear in the photo album of my mind.

A rainy, cold, windy morning. My father looks outside and tells me, “Stay home from school today and keep me company!” And if I can convince my mother that I don’t feel great, I stay at home. Now “keeping company” is a bit of a stretch. My father at home is busy at his desk, but we meet in the kitchen for a coffee or a snack. My father makes coffee in a small copper pot, boiling the water, adding coffee, bringing it to a boil again and inevitably spilling some as it boils over.

At lunch we eat together. A soft boiled egg, a bologna sandwich…”Aren’t you glad you stayed at home?” And he disappears behind the NYTimes, or Le Monde. There is no actual conversation, just the comfort of being at home, warm, dry and with my father.

In fact, I don’t remember having extensive discussions with my father, certainly nothing deep or soul searching, just the comforting dialogue of daily life.

Another snapshot: watching our favorite Carol Burnett show, if I could angle myself close to his hand, he would absent mindedly scratch my back throughout the entire half hour!

I inherited my father’s hands, rather thick fingers, not graceful at all. His were not healing hands but comforting hands. A heavy hand placed on a shoulder… and all anxiety would disappear, replaced by quiet peace.

What I didn’t inherit from my father was his amazing memory. He loved literature, Russian, French and English. He read so much. I know that one thing we didn’t skimp on in our house was books. And what a variety! My father loved poetry and knew it well. It was amazing what could trigger his memory, a forgotten glove on the road, a frosty morning, a lonely person walking by… he would recite a poem from start to finish…what a gift and how lucky we were to hear this poetry, for truly poetry is meant to be spoken aloud, not read in books.

As grandchildren began to appear, my father rejoiced and enjoyed the little ones who always felt secure and comfortable in his presence. He did not change diapers, he did not feed the babies. But in the evening the little ones, fresh from their baths would settle comfortably on his lap and next to him. He told an on-going story about Freddie the chipmunk who had all kinds of adventures. Sometimes he couldn’t resist and the story would become somewhat scary at which point the children would be hustled off to bed.

I asked my daughter Vera to share memories of her Grandfather with you today. I will read her reflections to you now:

My grandfather was for me a playmate at the beginning and end of every summer. I was fortunate enough to spend two weeks at the beginning and end of every summer with my grandparents in Labelle. My days were spent reading and swimming on my own enjoying the freedom experienced so rarely as an adult. Dede wrote and Babu pottered. The highlight of every day was my evening with Dede. Babu would prepare dinner while Dede wandered down to the beach very elegantly attired accompanied by his cane. At times, he would bring pocketfuls of change and offer me a trip to Alexandre’s, the local candy store. Eventually, our favorite way of traveling there together was by motorboat. In the beginning, I was always somewhat hesitant to start and drive the motorboat when my other cousins were around as I knew I hadn’t fully mastered running the boat. However, one day, Dede sat down in the boat and said “Gloopostsee, you are a smart and strong girl. We will sit here and enjoy the setting sun while you figure out how to start and drive the boat – I know you can do it .” It wasn’t so easy and there were tears, but I did finally master that boat. Since those days, the challenges I have faced in life have become more daunting and difficult. However, I always picture him facing me in the boat, outlined by the setting sun and staring off into the distance patiently waiting for me to start the boat as we drifted down the lake. It was his belief in my abilities from an early age that helped to nourish my feeling of self-worth and it is this belief encourages me to this day.

After dinner, we would play the board game Clue. The game itself wasn’t as important as the preparations. We would spend a good half hour drawing up our “Clue note pads”. We both believed that our own methods were the best but yet I never felt mocked or put down. I learned to share my views while feeling safe in the knowledge that those views would be listened to, perhaps argued with but NEVER mocked. What a gift…

I thank Vera for sharing her memories with you. Now back to my own reflections.

My parents have always not only loved nature, but they revered and sought opportunities to enjoy it throughout their life together. Nature for my parents meant walks, long walks in all kinds of places and in any weather. While still in Europe all holidays were in places of natural beauty which they explored together.

Once in the “New World”, North America, my parents sought a place where they could go in the summer, leaving behind the heat and bustle of Manhattan. My uncle, Serge Troubetzkoy, had told my mother about Lac Labelle in the Laurentians. From the very first visit until today, Labelle has been our summer refuge and a place of rest.

And my parents walked every day in Labelle. They would explore new places, new walks, and every walk had a name. One was called Versailles, because the fields, well grazed by cattle looked short and groomed like the gardens in Versailles. Another was named Chemin des Ruines, because there were remnants of an old stone house by the side of the road that resembled ancient ruins in Europe. Another route, Chemin Rita, because a young girl name Rita, who helped us at home lived there. Each walk special, each walk treasured for its particular beauty.

As an adult I was privileged to join these daily walks. And certainly I was happy to do so, leaving a baby in my sister’s care at naptime. For my father liked to walk right after lunch, in the heat of the day. He worked all morning so it was an afternoon walk. The speed with which my father walked was unbelievable. Today’s speed walkers would have a hard time keeping up with him!

My mother enjoyed walking but not at a run-walk pace, so she would let us go ahead and enjoy her own leisurely pace. We would walk until we would reach a predetermined spot where we would rest and my father would enjoy a cigarette.

I really treasure the memory of these walks. Even when my father was already quite sick with cancer, we walked every day. I would drive along the places where we used to walk, my father would get out at the rest spots, or we would share a coke in a little depanneur on the way home.

And we knew that these walks were the last ones. My father was slowly but steadily withdrawing from our world and getting ready for the next one. I remember during his last summer in Labelle he would talk about a third person on the walk, someone is here with us he would say, and it felt so natural that we were accompanied by an invisible presence, a warm and comforting presence.

And today, with my 86 year old mother we continue this tradition, and we walk, my mom at her pace, while I scoot ahead for a bit of exercise. And it really feels as though my father is there with us admiring the progress of summer or noticing a branch that has turned red before its time. I remember so well my father reaching for it with his walking stick to give a branch to my mother to enjoy at home.

So even today, we walk, gather flowers or leaves, and always my father is with us.

The very first summer that my parents came to Labelle, my Uncle Serge built a small chapel and so we were able to enjoy a normal church life even on vacation. To this day, the Lac Labelle community enjoys regular church services at St Sergius’ Chapel. When we were little, if there were a lot of children, my father would put on his summer white cassock and gather us together for “zakon bozhie”, a bit of church school. We would meet somewhere outside and I remember those sessions as being relaxed and enjoyable.

Another summer memory is “tikhie chas” or quiet time after lunch. As little kids we would gather under the big oak tree next to our house and my father or my mother would read to us. I don’t remember what we read. I know it was in Russian. I was very much younger than my brother and sister, but it’s a peaceful, quiet memory.

My father traveled a lot throughout his life. This is because he would never say no to an invitation unless he absolutely couldn’t be there. Sometimes he would take me along for company. I remember one visit to a small college where he would be addressing the students at chapel. The chaplain led a prayer which began, “Oh Lord, let us not be too avant-garde, but neither let us be too blasé.” We laughed so much remembering those words on our drive home!

My father loved people. He had many friends from all sorts of different backgrounds and found time to spend with them in spite of an incredibly busy schedule. Everything about people interested him and he read so many biographies and autobiographies often in an effort to understand a person that he could not agree with, whose world was so different from my father’s. I remember walking with him during the evening and we could see inside the homes of people going about their daily life. He wasn’t peeking, just enjoying the reminder that all humankind is loved by God, and this he found inspiring and awesome.

In the early years we lived in an apartment in NY. The building housed the entire St Vladimir’s Seminary spread out in small apartments. My parents were still very young when we first moved to America. As much as they loved nature and needed to spend time outside the city, they also loved the city. They had grown up in Paris after all, a city where each walk can lead to new places one more beautiful or more interesting than the other. And so, living in NY, they continued to walk and explore this great city and they fell in love with it. One day, walking along Amsterdam Avenue, they spotted a stray mutt, looking scared and alone. They picked him up and brought him home. Thus started the first in a series of dogs that we had until I got married and received a German shepherd as part of my “dowry”. We certainly didn’t train our dogs and they lived with us under the impression that they were lap dogs and our equals, although most of our dogs were rather big. And in the country they would chase skunks, get sprayed, chase porcupines and come home whining with their noses full of porcupine quills or burrs. My father loved removing the quills, cutting out the burrs, removing splinters from their paws. And the dogs submitted to his gentle touch with trust.

It seems that so many of my memories are summer ones. We were at leisure and had more time together! Swimming…another wonderful memory! In the early years at Labelle, we had no running water, an outhouse, and a real icebox to keep our perishables cool. So needless to say, bathing in the lake included soap, washcloths and shampoo. Every morning my father would go down to the lake for his morning ablutions, soap up his entire body, then charge into the lake at high speed swimming way out, then back to shore. This was way before the days of worrying about pollution and phosphates! (Did that word exist then?)

Volleyball has always been an integral part of summers in Labelle. In the early days we had the net on our big field. Everyday all would gather to play or watch the game. My father actually played very well. After each game all went down to the lake for a swim. But our field was uneven, and one day as my father leapt up to spike a ball he landed badly on his ankle and snapped literally all the bones in the ankle. A quick drive to Montreal and upon returning my father had a huge and heavy cast all the way up his leg! It was hot at that time and I remember my father using a bamboo slate to scratch his leg! No swimming? Impossible. My father was loaded on to a wheel barrow with his leg hitched high up and my uncle rolled him into the lake for a refreshing swim.

Nowadays the volley ball is played on the beach and so far we have avoided serious injuries.

As most of you know, my father was a twin. However no twins could be more different from each other than my uncle Andrei and his brother. Andrei was tall, balding, had a prominent beak nose and a deep booming voice. And although a deeply religious man and very involved in the church, my uncle was not a theologian. He worked in the art world. He considered himself to be an exile from Russia and always thought that he could return when all was restored to pre-revolution days.

My father’s relationship to Russia was so different. He knew and loved the literature. But he was a realist, had no intentions of returning to Russia. He did, however return in spirit. Every week he would tape a talk/sermon for Radio Free Liberty which was transmitted across the iron curtain. There are hundreds of these talks and they have just been released on DVD and in book form in Russia. What makes these recordings so special is that we hear his own voice. And of course his books could be found everywhere in Russian, even during the pre-détente period and when they were distributed via samizdat. It was in this way that Alexander Solzhenitsin became acquainted with my father and upon his exile his first request was to meet Alexander Schmemann. They met in the mountains of Switzerland, a memorable and precious encounter for both of them.

The brothers adored each other. Andrei came almost every summer to Labelle. My father was definitely not a gourmet. His favorite lunch in Labelle was a plain hotdog from a stand on the road. Not so my uncle. He had to have a sit down lunch with wine and cheese and dessert followed by an afternoon nap. Not surprising! These visits created a huge amount of work for my mother who loved her brother-in-law but was greatly relieved when his visit was over. She was a working woman and needed her summer rest!

The daily walks took place in the morning during these visits. Armed with walking sticks a pipe and cigarettes, they would stroll off at great speed leaving my mother, the chauffeur for these outings, behind them.

And so the years went on and here I find myself reaching the age that my father was when he left us over 25 years ago! But do you know what? He is still with us, a huge part of our lives! Today, when I am approached and told by countless people how my father changed their lives, how much he is loved and this without ever meeting him, I am so proud to be his daughter!

And I am proud to have an opportunity to share my memories with you today!

And so I end where I began. Alexander Schmemann?… He was my father.

Masha Schmemann Tkachuk

On this day in 1983 Father Alexander Schmemann died. He is a favorite liturgical theologian of the Orthodox Church. A prolific speaker and author, a man of great vision. May Father Alexander’s memory be eternal.

On this day in 1983 Father Alexander Schmemann died. He is a favorite liturgical theologian of the Orthodox Church. A prolific speaker and author, a man of great vision. May Father Alexander’s memory be eternal.