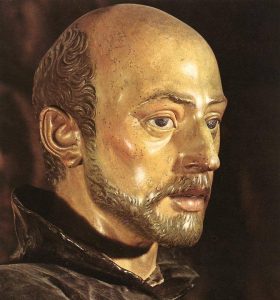

Saint Peter Julian Eymard (feastday today), whom Saint John Paul II called the “Apostle of the Eucharist.”

Saint Peter Julian Eymard (feastday today), whom Saint John Paul II called the “Apostle of the Eucharist.”

The prayer of the Church says:

O God, who adorned Saint Peter Julian Eymard with a wonderful love for the sacred mysteries of the Body and Blood of your Son, graciously grant, that we, too, may be worthy to receive the delights he drew from this divine banquet.

Saints are friends of saints, and saints beget saints: Eymard was a friend and contemporary of saints Peter Chanel, Marcellin Champagnat, and Blessed Basil Moreau. He died at the age of fifty-seven in La Mure on 1 August 1868.

At his canonization, Saint John XXIII said this of Saint Peter Julian:

It is also very fitting that the sacred ceremony occurs during the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council which has as its special purpose to see to it that the pearls of holiness belonging to the crown which encircles the head of the Church should sparkle and shine ever more and more. This extensive gathering of her holy shepherds united with the infallible successor of St Peter not only proposes and reaffirms once again the unchangeable truths left by the divine Master, but also clearly urges that daily, more and more, there be used those holy helps which make us possessors and sharers of divine grace. Furthermore, she enjoins on her children precepts designed to make the Christian way of life better lived.

The Council can therefore be said to have no other purpose than to show that here below, the Spouse of Christ possesses every kind of holiness both in deeds, in words, and in spiritual gifts of every kind; that here below she inspires her sons with that holy purpose of the Church expressed so clearly by the Redeemer of the human race: ‘Be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect’ (Matt., 5: 48).

Once these things are understood, it is easy to see that Christians should glory in having such a mother whom everyone ought to admire because of her incredible beauty, divinely infused. Her grandeur does not shine because of gems or pearls that can be seen by human eyes, but rather glows in the splendour and grace which derive from the blood of her Founder and the marvellous virtue of many of her children. As a result, whoever calls himself a Christian ought to observe a way of life which in no way detracts from the supreme honour of their mother and which is not foreign to her precepts and teachings. No one can truly say that he loves his mother who is not afraid of dishonouring her beauty, even a little, by his way of life.

The Eucharist, Source of Sanctity

Eucharistic life: The Holy Eucharist is the source and the nourishment of all sanctity. Our Predecessor, St Leo the Great, expressed this when he said: ‘The participation in the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ has no other effect than to transform us into Him whom we receive.’

How visible is this progressive transformation into the very life of the divine Saviour, in the admirable development of the virtues of the saints canonised today! And what dealings of particular intimacy with Jesus Eucharistic do we not discover in their ascent to sanctity! The name of Peter Julian suffices to unveil to our eyes the splendid eucharistic triumphs to which, in spite of trials and difficulties of all kinds, he wanted to consecrate his life which prolongs itself in the family founded by him. This little child of five who was found on the altar, his forehead resting on the little door, was the same person who in time would found the Congregation of the Fathers of the Blessed Sacrament and that of the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament, and who would radiate into innumerable armies of priest adorers, his love and tenderness for Christ living in the Eucharist…

Marian Piety: At the side of Jesus there stands His Mother, the Queen of all the Saints, the source of sanctity in the Church of God and the first flower of its grace. Intimately associated with the redemption in the eternal plans of the Most High, the Blessed Virgin, as Severiano di Gabala expressed it in song, ‘is the Mother of salvation, the source of light become visible’. Hence filial piety is pleased to consider her at the beginning of all Christian life to ensure its harmonious development and to crown its fullness by her maternal presence.

Thus it is not surprising to meet the Blessed Virgin Mary in the life of the three new confessors whom she accompanies step by step. Saint Julian Eymard proposes her as a model to adorers, invoking her as ‘Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament’…….

….pastoral radiance – the new saints prove it – can be described as the formation of good priests, with fervent souls of adorers, whose ranks have multiplied throughout the world… a

Perfect Adorer of the Blessed Sacrament

We now desire to add a word for the French pilgrims who have come to assist at the glorification of St Peter Julian Eymard, priest, confessor, founder of two religious families consecrated to the worship of the Blessed Sacrament.

He is a saint with whom We have been familiar for many years, as We said above, when as Apostolic Nuncio to France, Providence granted Us the happy opportunity to visit his native land, La Mure d’Isère, near Grenoble.

We saw with Our own eyes the poor bed, the humble dwelling where this faithful imitator of Christ gave up his beautiful soul to God. You can surmise, beloved Sons, with what emotion We recall that memory on this day when it is given Us to confer upon him the honours of canonisation.

The body of St Peter Julian Eymard is preserved in Paris: but the saint is also somehow present at Rome, in the person of his sons, the Priests of the Blessed Sacrament; it is also a sweet memory for Us to recall visits that We used to make to their Church of St Claude-des-Bourguignons (San Claudio), to unite Ourselves for a few moments to their silent adorations.

Besides St Vincent de Paul, St John Eudes, the Curé of Ars, Peter Julian Eymard takes his place in the ranks of the incomparable glory and honour of the country that witnessed their birth, but whose beneficial influence extends far beyond, namely, to the whole Church.

His characteristic distinction, the guiding thought of all his priestly activities, one may say, was the Eucharist: eucharistic worship and apostolate. Here, We would like to stress this fact in the presence of the Priests and of the Servants of the Most Blessed Sacrament, in presence also of the members of an Association which is dear to the heart of the Pope, that of the Priest Adorers assembled at this time in Rome, who have come in great numbers to honour this great friend of the Eucharist.

Yes, dear Sons, honour and celebrate with Us him who was so perfect an adorer of the Blessed Sacrament; after his example, always place at the centre of your thoughts, of your affections, of the undertakings of your zeal this incomparable source of all grace: the Mystery of Faith, which hides under its veils the Author Himself of grace, Jesus the Incarnate Word.

+++

Eymard is a great teacher for those who want to know more about the Eucharist and to have devotion to the Eucharist. It is this Mystery of the Faith which the Church infallibly teaches us is the center, summit and source of All.