|

After two Salesians, now a son of Saint Ignatius will be second in command of the first of the Congregations of the Roman Curia.

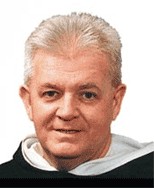

An interview with Archbishop

Luis Francisco Ladaria Ferrer

|

by Gianni Cardinale

After two Salesians, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has a Jesuit as its new secretary. On 9 July in fact Benedict XVI appointed as number two in the Department, that he himself directed from 1981 to 2005, the Spaniard Luis Francisco Ladaria Ferrer, 64 years old, originally from Manacor, the second city, after Palma, of the island of Majorca in the Balearic Islands.

Ladaria takes the place of the Salesian Angelo Amato, promoted Prefect of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, who in turn succeeded another son of Don Bosco, the then Archbishop Tarcisio Bertone, who as Cardinal Secretary of State consecrated Ladaria bishop in the Basilica of Saint John Lateran on July 26.

30Days met the new secretary, in the Palace of the Holy Office, on his return from vacation, passed mostly in his homeland. In answer to the observation that he didn’t look very tanned, Monsignor Ladaria smilingly said: “That comes of the fact that I love the sea, much less the sun…”. Before the interview Ladaria spoke of his origins, explaining that, although his family has been rooted for generations in the Balearic Islands, perhaps his ancestors came from the Kingdom of Naples, and more specifically from the Gulf of Policastro. But the pleasantries end there. And the questions begin.

Your Excellency, how did your vocation come about and why did you choose the Society of Jesus?

Luis Francisco Ladaria Ferrer: Perhaps the word “choose” is not correct. It was not I who chose but I saw a road in front of me and set out on it. A road, that of vocation, that I began to see when I attended the Jesuit College in Palma de Mallorca and then while studying Law in Madrid. I studied law but I realized that was not what I wanted. I wanted to become a priest and I liked the Society of Jesus which I knew. And so it was a path open before me that I set out on almost naturally.

Was your family very religious?

LADARIA FERRER: Fairly.

Was there some priest figure who particularly influenced you?

LADARIA FERRER: Certainly, I have before me the faces of the fathers of the College I attended, the old College of Mount Zion, founded in 1561, but it was rather the whole environment, the air one breathed, that brought me to devote myself entirely to God.

You took your religious vows in 1968. What memory do you have of that year, so turbulent at least outside Spain?

LADARIA FERRER: It was a turbulent year in Spain also. But I quietly took my vows, without paying too much attention to the the turbulence. I liked studying and I studied.

Did you ever feel the fascination of ’68?

LADARIA FERRER: Maybe we are all a little conditioned by ’68, but in my case not in any special way.

Who were your teachers?

LADARIA FERRER: I am pleased to remember a few. In Frankfurt in Germany, where I studied theology, I had as professors Father Grillmeier, who then became a cardinal, who was a great scholar of Dogma, Father Otto Semmelroth and Father Herman Josef Sieben, at the beginning of his academic career, who would then become one of the world’s greatest experts on the concept of Council. In Rome I did my graduate thesis with Father Antonio Orbe, a great patrologist, and I had as professors Fathers Juan Alfaro and Zoltan Alszeghy.

You also studied in Germany. Did you ever meet Professor Ratzinger?

LADARIA FERRER: Not personally. But I knew his writings. In particular his Introduction to Christianity which was his best known work, but also his book on the People of God. I remember that even in our faculty lecture notes of some of the courses of the then Professor Ratzinger circulated.

And when did you personally come to know the current Pontiff?

LADARIA FERRER: In 1992 when I became a member of the International Theological Commission. I recall with pleasure the detailed discussions that took place on the subject of relations between Christianity and other religions. The intervention of Cardinal Ratzinger was always very precise and profound and the discussion was always at a very high level. The work of that Commission is very interesting both for the topics dealt with, always of great importance, and for the international and Catholic air, that one breathes there.

Did you have a role in the drafting of Dominus Iesus?

LADARIA FERRER: No.

Your degree at the Gregorian was on Saint Hilary of Poitiers. Why that choice and what attracted you to that saint?

LADARIA FERRER: The topic was proposed by Fr Orbe who was interested in that Father of the Church. I was lucky because there was not a great bibliography on Saint Hilary, so I could better devote myself to reading his original texts directly. Saint Hilary was not studied enough at the time, but since then many works about him and many translations have appeared, especially in France. And yet he is the demonstration that the Patristic era in the Latin Church did not begin with St. Augustine, who indeed knew, and often cited, Saint Hilary.

What is the relevance of Saint Hilary?

LADARIA FERRER: It doesn’t take much effort to find out the relevance of the Fathers of the Church. We have to read and savor them to be better able to approach the freshness of the Gospel message, Jesus, and that is of permanent value rather than something tied to what is topical, which by its nature is variable, changing minute by minute. The Fathers of the Church are a source that springs in an era closer to the apostolic one. That’s what makes them always relevant.

Father Orbe was an expert on Saint Irenaeus and Gnosticism …

LADARIA FERRER: In effect, he was one of the greatest experts on the subject. He wrote many books on these subjects, to be honest often complicated because the material is difficult.

For many years you were a teacher at the Gregorian and vice-rector. What did you learn in all these years?

LADARIA FERRER: The fact that I was vice-rector for eight years is not very important. What is important was the teaching, the supervision of the theses. The Gregorian taught me to live in an international environment with students from over one hundred countries, of different languages, races and cultures. All united by the love of study, but above all of the Lord and His Church. In a real university students not only learn from professors, but also the reverse occurs. And I learned a lot from my students.

When your appointment was made public, John Allen Jr. of the National Catholic Reporter collected some opinions on you from your colleagues. Some have called you gentle and affable …

LADARIA FERRER: I must say that I try to be, but it must be up to others to say whether I succeed …

There are also those who described you as a moderate conservative and theologically centrist. Do you recognize yourself in those descriptions?

LADARIA FERRER: I must say that I don’t like extremisms, either progressive, or traditionalist ones. I believe that there is a via media, which is taken by the majority of professors of Theology in Rome and in the Church in general, which I think is the correct path to take, even if each of us has his own peculiarities, because, thanks be to God, we do not repeat, we are not clones.

Your appointment did not please the traditionalist world. In Spain the theologian Don José María Iraburu accused your Theology of original sin and grace of not conforming to the doctrine of the Church, while the periodical “Sì sì No no” even wrote that your book Theological Anthropology “is completely outside the Catholic dogmatic tradition.” Are you concerned about these judgments?

LADARIA FERRER: Everyone is free to criticize and make the judgments they want. If you ask me if I’m concerned I have to say that these opinions don’t concern me too much. Besides, if I was appointed to this office, I must presume that my works do not deserve these judgments.

You gained a certain notoriety when the Theological Commission published the document on the salvation of children who died before baptism. In it Limbo was finally thrown out of the Magisterium?

LADARIA FERRER: The International Theological Commission has no power to throw anything or anybody out. Although it is formed not by private theologians but ones appointed by the Pope, its conclusions do not have magisterial value. The document in question reiterates that the doctrine of Limbo, which for centuries was accepted by the majority and dominant in theological reflection, was never defined dogmatically and therefore was never a part of the infallible magisterium. And it does not mean that those who still want to continue to speak of Limbo are outside the Catholic Church because of it. That said, however, the Theological Commission, considering together the revealed data and the universal salvific will of God and the universal mediation of Christ, wrote that there are more appropriate ways to address the issue of the fate of children who die without having received baptism, for whom a hope of salvation cannot be ruled out. These conclusions are not new to tell the truth, they originated around the time of the Council, but bring together the fruits of a very broad theological consensus today.

How do you feel about being the first Jesuit to hold this position?

LADARIA FERRER: I must say that I didn’t pose myself the problem. Even if it’s true that it seems no Jesuit has ever held the position. I believe that the Holy Father chose me not as a Jesuit but because, I imagine, I seemed to him the best person.

How did you learn of the appointment?

LADARIA FERRER: That was very surprising. I would never have thought of ending up here. And not just me, seeing that my name was never mentioned in the newspapers … Until the evening of June 24, when I was told that the Holy See was considering giving me this job. For my part I explained my state of mind about this prospect and I indicated that in any case I accepted the decision of the Holy Father.

As a Jesuit did you have to ask permission of the Provost General first?

LADARIA FERRER: Yes, we Jesuits have a vow that prevents us from receiving episcopal appointments if not out of obedience. And the Provost General told me that I should accept the will of the Pope.

Adolfo Nicolás, Superior General since January, Spanish like you. Do you know him well?

LADARIA FERRER: I had heard of him, I knew him by name, but not personally. I met him for the first time only the day after his election, January 20. Then I went to visit him on the issue of my nomination.

Another well-known Spanish Jesuit is Antonio Martínez Camino, who became the first follower of St. Ignatius to be made bishop in Spain as auxiliary of Madrid. Do you know him?

LADARIA FERRER: Absolutely. He was my student and so I know him well. And we are good friends.

You have practically lived in Rome since 1979. What do you think of Spain today? Do you identify with it?

LADARIA FERRER: Certainly Spain has changed a lot: in the political, religious, cultural, economic spheres. But I must say that when I return to my country to relax I do not deal with major issues of doctrine or policy. I visit my family, my friends, my background again, and I don’t find my background of always much changed.

Recently, your superior, Cardinal Levada, in Spain for a conference, issued a cry of pain at the measures announced by the Zapatero Government about the extension of the right to abortion …

LADARIA FERRER: At present Spain is undergoing a worrying drift on ethical issues.

Do you have any hobbies apart from books of theology?

LADARIA FERRER: I like to listen to music. Classical, preferably. Johann Sebastian Bach in particular, but without undervaluing the others.

Enthusiasm for sport?

LADARIA FERRER: No, I follow the major events a little, but from very far off.

You, along with Cardinal Levada, were received in audience by the Pope in Castel Gandolfo on September 10. It was the first audience as Secretary of the Congregation. What can you tell us about it?

LADARIA FERRER: It was a beautiful experience. The Holy Father, as always, was very welcoming and kind.

What are the main issues that the Congregation finds itself facing?

LADARIA FERRER: I can say that our Congregation is concerned with promoting and protecting the Catholic faith. First promoting and then, if necessary, protecting. But I can’t go into details. Our Congregation always moves with discretion and speaks exclusively through its acts.

courtesy of 30 Days

When our Lord Jesus Christ, beloved, was preaching the gospel of the Kingdom, and was healing various sicknesses through the whole of Galilee, the fame of His mighty works had spread into all Syria: large crowds too from all parts of Judæa were flocking to the heavenly Physician (Matthew 4:23-24). For as human ignorance is slow in believing what it does not see, and in hoping for what it does not know, those who were to be instructed in the divine lore, needed to be aroused by bodily benefits and visible miracles: so that they might have no doubt as to the wholesomeness of His teaching when they actually experienced His benignant power. And therefore that the Lord might use outward healings as an introduction to inward remedies, and after healing bodies might work cures in the soul.

When our Lord Jesus Christ, beloved, was preaching the gospel of the Kingdom, and was healing various sicknesses through the whole of Galilee, the fame of His mighty works had spread into all Syria: large crowds too from all parts of Judæa were flocking to the heavenly Physician (Matthew 4:23-24). For as human ignorance is slow in believing what it does not see, and in hoping for what it does not know, those who were to be instructed in the divine lore, needed to be aroused by bodily benefits and visible miracles: so that they might have no doubt as to the wholesomeness of His teaching when they actually experienced His benignant power. And therefore that the Lord might use outward healings as an introduction to inward remedies, and after healing bodies might work cures in the soul. wish to arrive at eternal blessedness may understand the steps of ascent to that high happiness. “Blessed,” He says, “are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3). It would perhaps be doubtful what poor He was speaking of, if in saying blessed are the poor He had added nothing which would explain the sort of poor: and then that poverty by itself would appear sufficient to win the kingdom of heaven which many suffer from hard and heavy necessity. But when He says blessed are the poor in spirit, He shows that the kingdom of heaven must be assigned to those who are recommended by the humility of their spirits rather than by the smallness of their means. Yet it cannot be doubted that this possession of humility is more easily acquired by the poor than the rich: for submissiveness is the companion of those that want, while loftiness of mind dwells with riches. Notwithstanding, even in many of the rich is found that spirit which uses its abundance not for the increasing of its pride but on works of kindness, and counts that for the greatest gain which it expends in the relief of others’ hardships. It is given to every kind and rank of men to share in this virtue, because men may be equal in will, though unequal in fortune: and it does not matter how different they are in earthly means, who are found equal in spiritual possessions. Blessed, therefore, is poverty which is not possessed with a love of temporal things, and does not seek to be increased with the riches of the world, but is eager to amass heavenly possessions.

wish to arrive at eternal blessedness may understand the steps of ascent to that high happiness. “Blessed,” He says, “are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 5:3). It would perhaps be doubtful what poor He was speaking of, if in saying blessed are the poor He had added nothing which would explain the sort of poor: and then that poverty by itself would appear sufficient to win the kingdom of heaven which many suffer from hard and heavy necessity. But when He says blessed are the poor in spirit, He shows that the kingdom of heaven must be assigned to those who are recommended by the humility of their spirits rather than by the smallness of their means. Yet it cannot be doubted that this possession of humility is more easily acquired by the poor than the rich: for submissiveness is the companion of those that want, while loftiness of mind dwells with riches. Notwithstanding, even in many of the rich is found that spirit which uses its abundance not for the increasing of its pride but on works of kindness, and counts that for the greatest gain which it expends in the relief of others’ hardships. It is given to every kind and rank of men to share in this virtue, because men may be equal in will, though unequal in fortune: and it does not matter how different they are in earthly means, who are found equal in spiritual possessions. Blessed, therefore, is poverty which is not possessed with a love of temporal things, and does not seek to be increased with the riches of the world, but is eager to amass heavenly possessions.