Every day we have the opportunity of renewing our commitment, our energy, our intention and creative talents to the realization of the Kingdom of God on earth. Though this work is a process, it implies acknowledging and affirming our true identity: that we are members of the Body of Christ — Christ’s mystical body — and that our destiny can never be fulfilled independent of conscious communion with this reality. (NS)

Category: Spiritual Life

Which agenda comes first?

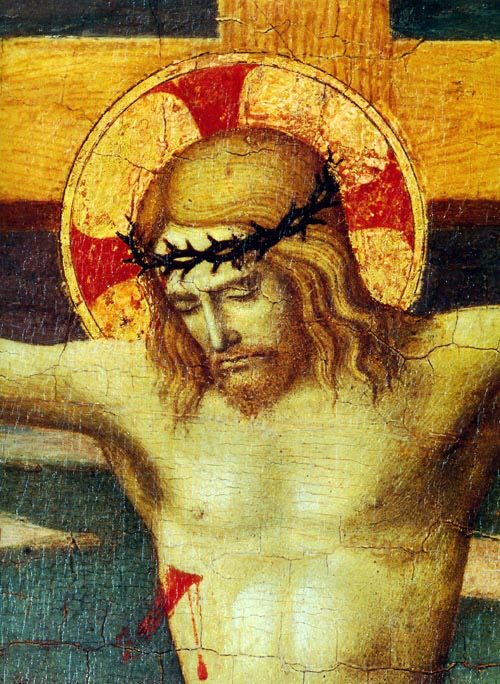

The attitude of putting our agenda ahead of others is perhaps one of the biggest obstacles to the manner of seeing and hearing the word of God within us, to really listen to our soul consciousness. Practicing soul consciousness allows us to see blessedness around us; the mystery of the cross cuts through the blindness of egocentricity to see what is most precious in life, to notice the subtle sensitivity around us, to feel connected with ourselves, with others and with creation. Paradox of paradoxes: what is felt as death-dealing is in fact life-giving. Isn’t this why we surround the cross with flowers during the feast of the Holy Cross? The cross viewed in this light is blessedness in the deepest sense of the word. It is the path to the deep-seated learning to live in the spirit of the beatitudes. (NS)

Being watchful

“Being watchful is intimately connected with a sustained and disciplined practice of meditation. Taking the time each day to try to discern the movement of the Spirit prepares us to recognize, to intuit God’s presence and respond wholeheartedly. No matter the form your external meditation takes, the fruit of dedicated practice comes in being able to knit together the various moments of each day in conscious, fully awake action.” (NS)

An authentic and fruitful formation in the spiritual life requires us to develop a capacity to be watchful, an awareness, a contemplative gaze. We are bombarded with images and noise: distractions to the point we forget that we are in communion with others. Being watchful as it is noted in the quote above, “sustained and disciplined by practice of mediation.” The Lord revealed to us of the necessity for us to be watchful casting off our sleepiness. The sleepy ignores the Kingdom of God; the person who is not watchful is unconcerned for salvation, that is, our salvation.

Father Luigi Giussani recalls for us that the Gospel says, “Be watchful! Be alert! You do not know when that time will come,” it means be conscious of your destiny, of your relationship with God, with the source, the substance, and the end of what you are…. If we immediately want to feel ourselves filled with richness in our contemplative life, we must always start from the original truth: we were not and now we are. Therefore being—living, existing, moving—is participation in something else. How peacefully exhaustive it is to be able to say with clarity (clarity regarding your motivation, not regarding content, which is the mystery that Christ has revealed to us) that everything we do participates within something else. This is where gratuity is rooted: everything that we do and that we are is given to us; we participate in something else. I believe that there exists nothing more evident than this: no instant in our life do we make ourselves. It is in the vibration of this self-awareness that the possibility of real prayer is developed within us.

leave holiness behind?

Benedictine Spirituality I: Listen

Father Boniface Hicks, OSB, a Benedictine monk of Saint Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. He is trained in computer science and in spirituality. Currently, Father Boniface is part of the formation team training men for the Catholic priesthood at his abbey’s seminary and the work of spiritual direction. Since I am interested in Benedictine Spirituality periodically you will see essays on this subject here on Communio. As a side note, those of us who follow Communion and Liberation ought to recognize a connection with what is said here and with what Father Julián Carrón has been teaching in months. That is, the importance of listening, centering on Jesus Christ as a Lord and Savior, and that silence is crucial method. How we respond to the Lord’s invitation to be in friendship with him requires us to be in relation to Him and listen to His promptings through prayer, fasting, alms-giving, sacred scripture, the worthy reception of the sacraments and knowing the faith.

What is said of monks is also true for the Oblates. Attend!

Introduction

“Listen my son to the Master’s instructions and attend to them with the ear of your heart” (Prologue 1). These are the first words Saint Benedict speaks to his monks through his Rule of life. The Rule of Benedict (RB) establishes three important spiritual attitudes already in the first verse. The first instruction is that Saint Benedict requires the monk to listen, which requires the monk to cultivate silence, humility and obedience. The second is that God, the Master, speaks to us—both directly and through those in whom He has invested authority, and even more broadly through the circumstances of reality itself. The third is that there is a kind of listening that one can only do and must do with the ears of the heart. In this post, we will reflect on the first part and take up the next two parts in the following posts.

Listening – “Listen, my son”

Listening is the foundational attitude of the monk and to do it well it requires silence, obedience, and humility. This explains the three chapters of the Rule on these principal monastic attributes—chapter 5 on obedience, chapter 6 on silence and chapter 7 on humility. All are necessary for listening: only the humble man listens, while the proud man believes he already knows everything; listening requires exterior silence to hear with the ears in one’s head and interior silence to hear with the ears of the heart, and obedience treats listening as a path of potential action, not merely a matter of taking in idle words.

Humility is a key theme throughout the Rule of Saint Benedict. The longest chapter in the rule (chapter 7) is devoted to the virtue of humility. Humility is expressed in the beginning of the rule as the call to listen. A person only listens when he believes he has something to learn. Otherwise, he will talk excessively, thinking everyone else has something to learn from him. That is why Saint Benedict warns the talkative man: “in a flood of words, you will not avoid sinning” (RB 7:57 quoting Proverbs 10:19). He also notes that when we think we know everything and never cease talking, we end up going in circles, never making progress: “A talkative man goes about aimlessly on the earth” (RB 7:58 quoting psalm 140:12). Those scriptures are quoted in the ninth step of humility which requires “that a monk controls his tongue and remains silent” (RB 7:56).

The silence of Christian monasticism is not merely an asceticism of self-control or emptying our desires, but rather a posture of listening to a God who speaks. We do not silence ourselves for the sake of being silent, but rather for the sake of hearing more clearly. Our silence is not a matter of isolating ourselves, but rather of opening ourselves. It is relational. Silence is the necessary pre-condition for hearing God and encountering Him in prayer and in life. Too often we make the mistake of getting lost in the world and never slowing down enough or silencing ourselves enough to meet God, to hear Him, and simply to be with Him. God has revealed Himself as the divine Word who has spoken from all eternity and continues to speak to us in a personal relationship. When we slow down, humble ourselves in prayer and open our hearts, we can hear His voice. That has a way of humbling us even more, reducing our inflated egos to nothing. We find ourselves saying like Saint Paul, “Indeed I count everything as loss because of the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord” (Phil 3:8).

Furthermore, Saint Benedict understands listening as leading to action. He is not content with ideas that never turn into action nor with knowledge that never becomes love. “’Knowledge’ puffs up, but love builds up” (1Cor 8:1). “The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14). It is through obedience that knowledge becomes love and that the Word becomes flesh. That is why Jesus is the ultimate example of obedience. In Him, the Father’s will was made tangible and visible at every moment of His life (cf. 1 Jn 1:1-4). “Consequently, when Christ came into the world, he said, ’Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired, but a body have you prepared for me’” (Heb 10:5). The Word was made flesh so that the Father’s will could be visible in a human body. Furthermore, the ultimate sacrifice is made through that same human body. There is no love without sacrifice and Christ revealed the ultimate love by offering the ultimate sacrifice. He laid down His life for us, allowing His crucified Body to proclaim, through suffering, all of the Father’s love for us. When Jesus listened to the Father, He opened His life to the greatest potential. This potential became a reality as His Body participated in and revealed the fullness of divine love. This is true obedience and Saint Paul glorifies it by singing: “Christ…became obedient unto death, even death on a cross” (Phil 2:8).

We can now apply to ourselves Saint Benedict’s teaching on listening through silence, obedience, and humility. We must create places of silence and we must intentionally include in our lives extended periods of silence for prayer. In the rule, Saint Benedict prescribes 4-6 hours of silence for monks to spend each day in personal prayer. This sets a high standard that few can follow given the demands of daily life, but at least an hour of daily silent prayer is necessary for real spiritual growth.

Beyond our dedicated times of silent prayer, it also helps to create spaces of communal silence. Benedictine monasteries have done this since the 6th century, making a place not only for the personal sanctification of the monks but also for other members of the faithful to enter into. Saint Benedict had extensive regulations in the Rule to provide for guests, noting that “monasteries are never without them” (RB 53:16). The service of hospitality is a key feature of Benedictine spirituality. When Benedictine monasteries consist of monks that are prayerful and cultivate silence, these monasteries can become a spiritual oasis for the faithful. That depends on the personal decision of the monks, however. We must all choose how we will respond to the call of the Christian faith. When we respond with humble silence and holy love, our hearts are set aflame and we can warm the hearts of others. When we allow the noise of the world to come in and to corrupt our souls and make us busybodies, our hearts grow cold and so do those who would seek the warmth of Christ in us.

This post originally appeared on fatherboniface.org

Hesychia: necessary for monk and lay person

Throughout the history of Eastern monasticism, there has always been an understanding of silence and solitude that has been called “hesychia”. Hesychia refers to a state of inner stillness and stability that is increasingly able to discern the presence of God in the length and breadth of the everyday. It involves an attitude of listening that focuses the heart, regardless of what one happens to be doing. But the truth is, such silence does not come cheap. It requires practice, a type of spiritual practice that leads one through many levels of growth. This has its analogy in athletic practice, where to reach excellence demands self-sacrifice, personal commitment, making mistakes, and hours and hours of work. (thanks to NS)

Beauty in our life through ritual

The life we lead is informed by the gestures and intentions we do and have. I ask myself what judgment –that is, what is the meaning– of how and why I do things, and how the things I say and do have an impact on my own soul and that of others. The perspective of the author is the Byzantine Liturgy but if one looks a little deeper into the Latin similar gestures are present but often neglected. Catholicism, East and West, is an embodied faith. Consider what the Lord did with the 12, with the 72, and how He engaged and loved them. What was seen with Jesus is now passed into the Church. But sometimes we have neglected the body ethic to our detriment. It does not have to be THAT way. We can attend to how we use our bodies to worship the Lord, to pray, to contemplate holy things, and to act as witnesses to the Good News revealed to us.

“How do we make our life a work of art? One of the important benefits of liturgical prayer and the rituals that accompany it is that it teaches us how to meet each moment with our best intention, and to approach our daily life as an arena of spiritual practice. By focusing on the quality of our presence at Divine Liturgy, for example, by consciously entering into the ritual movements that accompany the prayer — the sign of the cross, the reverence, the kissing of the icon — our presence during this time becomes choreographed. There is nothing artificial in this, but rather it is a means of creating beauty. Our body is responding to the mystery that is before us, and this in turn conditions us to pay attention to our movements outside liturgy, in the various rhythms of daily life. If we are conscious and mindful of God’s presence throughout the day, life can increasingly become a work of art, one that honors the dignity of our humanity.” (NS)

St Joseph models work

Yesterday (May 1), we observed the Memorial of St. Joseph the Worker. The history of this feast is rooted in the ideology of work propagated by Communists and Pope Pius XII wanted to remind Catholics that theory of work of the Communists contradicted what the Church (and by extension St. Benedict) taught about work so he instituted the feast of Saint Joseph the Worker. That was 1955.

Yesterday (May 1), we observed the Memorial of St. Joseph the Worker. The history of this feast is rooted in the ideology of work propagated by Communists and Pope Pius XII wanted to remind Catholics that theory of work of the Communists contradicted what the Church (and by extension St. Benedict) taught about work so he instituted the feast of Saint Joseph the Worker. That was 1955.

Pius XII considered St. Joseph to be the model of work: “The spirit flows to you and to all men from the heart of the God-man, Savior of the world, but certainly, no worker was ever more completely and profoundly penetrated by it than the foster father of Jesus, who lived with Him in closest intimacy and community of family life and work.”

In his encyclical Laborem Exercens, Pope St. John Paul II wrote: “…the Church considers it her task always to call attention to the dignity and rights of those who work, to condemn situations in which that dignity and those rights are violated, and to help to guide [social] changes so as to ensure authentic progress by man and society.”

The coronavirus has many of us on a work hiatus it so it seems like a good time to break this great encyclical out and read or reread it. Do you consider your professional work to have meaning for your life in the family, does your professional life have dignity and an importance that you can see it as cooperating with the work of God in building up the Kingdom of God? Is there a creative genius that connects with the care of the land as proposed by Genesis 2:15?

HOLY THURSDAY, APRIL 9, 2020

O my Lord, you only are our King; help me, who am alone and have no helper but you, for my danger is at hand. . . .You, O Lord, did take Israel out of all the nations. . .for an everlasting inheritance. . . .And now we have sinned before you, and you have given us into the hands of our enemies, because we glorified their gods. You are righteous, O Lord! . . .Remember, O Lord; make yourself known in this time of affliction and give me courage. (Esther 14:3-7)

The Mystical Body of Christ

There are some things about Catholic faith which is understood keenly by the sacramental churches of East and West that need continue reflection upon. Lots of other Christian communities have neither a reference point nor a ritual for the Eucharistic Presence. The theology of the Mystical Body of Christ is one of those pieces of dogma that meets the criteria for the need to understand more deeply and to feel where it impacts our lives on a daily basis. To “feel” is not aiming toward a sentimentality; the sentimental is vacuous; to feel means really means for me and I am sure for the Church something concrete and personal because it pertains to the heart, the mind and one’s behavior. How we encounter the Mystical Body of Christ and how the Mystical Body of Christ encounters us is the matrix. The mystical body of Christ is not tribal because it encompasses everyone. As an example, I pray for generic intentions and intentions that have a history, a name … a real person. Praying for world peace is important. But I think it is critically important to actually name in a concrete way who and what we are praying for. Yet, if we are honest Christians we’d know that the Mystical Body of Christ is not abstract and that there is real content for our lives: we have a loved ones, friends, enemies, work experiences, desires, etc. Moreover, we ought to realize that our life in the Mystical Body of Christ has implications how we live and work with one another, how we pray in community, how we care for the needy, the lonely, the sick and those prone to depression and the like. We live life in a personal way and not in sense of social disengagement.

There are some things about Catholic faith which is understood keenly by the sacramental churches of East and West that need continue reflection upon. Lots of other Christian communities have neither a reference point nor a ritual for the Eucharistic Presence. The theology of the Mystical Body of Christ is one of those pieces of dogma that meets the criteria for the need to understand more deeply and to feel where it impacts our lives on a daily basis. To “feel” is not aiming toward a sentimentality; the sentimental is vacuous; to feel means really means for me and I am sure for the Church something concrete and personal because it pertains to the heart, the mind and one’s behavior. How we encounter the Mystical Body of Christ and how the Mystical Body of Christ encounters us is the matrix. The mystical body of Christ is not tribal because it encompasses everyone. As an example, I pray for generic intentions and intentions that have a history, a name … a real person. Praying for world peace is important. But I think it is critically important to actually name in a concrete way who and what we are praying for. Yet, if we are honest Christians we’d know that the Mystical Body of Christ is not abstract and that there is real content for our lives: we have a loved ones, friends, enemies, work experiences, desires, etc. Moreover, we ought to realize that our life in the Mystical Body of Christ has implications how we live and work with one another, how we pray in community, how we care for the needy, the lonely, the sick and those prone to depression and the like. We live life in a personal way and not in sense of social disengagement.

It is challenging for all of us to sit silently with the Scripture in Lectio Divina to give serious time to praying and thinking about reality rather than abstract data.

First the Scripture

For just as the body is one and has many members, and all the members of the body, though many, are one body, so it is with Christ. For in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit.

Indeed, the body does not consist of one member but of many. If the foot would say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” that would not make it any less a part of the body. And if the ear would say, “Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body,” that would not make it any less a part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the hearing be? If the whole body were hearing, where would the sense of smell be? But as it is, God arranged the members in the body, each one of them, as he chose. If all were a single member, where would the body be? As it is, there are many members, yet one body. (1 Corinthians 12:12-20)

Second the Reflecti0n

We are familiar with the concept of the Mystical Body of Christ, imaged as an organic unity, a single living organism. Each member makes a particular contribution drawing the whole into tighter communion. This living body can be seen to even extend to those who are not official members of our church, maybe not even Christians. There can be a sense of the sacred, the feeling that God is somehow resident in the interactions of these shared relations, shared lives, contributing to the unity of the whole. It is the actions of the members toward one another that constitutes the unity. The Persons of the Trinity love one another to the extent of “indwelling” one another. The members of the Mystical Body are to love one another and share the various gifts of our lives. (NS)