In speaking to the Benedictines at Montecassino, the Pope was speaking to all Benedictines, solemnly professed and oblates, and to the laity, in general. He proposes once again the person of Saint Benedict as a person who knew well that Christ is the answer to all things. The Pope’s homily at Vespers follows:

In speaking to the Benedictines at Montecassino, the Pope was speaking to all Benedictines, solemnly professed and oblates, and to the laity, in general. He proposes once again the person of Saint Benedict as a person who knew well that Christ is the answer to all things. The Pope’s homily at Vespers follows:

Almost at the end of my visit today, I am particularly pleased to pause in this sacred place, in this abbey, four times destroyed and rebuilt, the last time after the bombings of World War II, 65 years ago. “Succisa virescit” [in defeat we are strengthened; when cut down, this tree grows again]: the words of its new coat of arms represent well its history. Monte Cassino, just as the secular oak tree planted by St. Benedict, was “pruned” by the violence of war, but has risen more vigorous. More than once I also have had the opportunity to enjoy the hospitality of the monks, and in this abbey I spent many unforgettable hours of quiet and prayer. This evening we entered singing “Laudes Regiae” together to celebrate the Vespers of the Solemnity of the Ascension of Jesus. To each of you I express the joy of sharing this moment of prayer, greeting everyone with affection, grateful for the welcome that you have reserved for me and those who accompany me in this apostolic pilgrimage.

In particular, I greet Abbot Dom Pietro Vittorelli, who has made himself the spokesman of your common sentiments. I extend my greetings to

the abbots, the abbesses, and to the Benedictine communities present here.

Today the liturgy invites us to contemplate the mystery of the Ascension of the Lord. In the brief reading taken from the first letter of Peter, we were urged to fix our gaze on our Redeemer, who died “once and for all for sins” in order to lead us back to God, at whose right hand he sits “after having ascended to heaven and having obtained sovereignty over the angels and the principalities and the powers” (cf. 1 Pt 3, 18.22). “Raised on high” and made invisible to the eyes of his disciples, Jesus has not however abandoned them, but was: in fact, “put to death in the body, but made to live in the spirit” (1 Pt 3:18). He is now present in a new way, inside the believers, and in him salvation is offered to every human being without distinction of people, language, or culture. The first letter of Peter contains specific references to the fundamental Christological events of the Christian faith. The Apostle’s intention is to highlight the universal scope of salvation in Christ. A similar desire we find in St. Paul, of whom we are celebrating the two thousandth anniversary of his birth, who to the community of Corinth, writes: “He (Christ) died for all, so that those who live, live no longer for themselves but for him, who has died and is risen for them.” (2 Cor 5, 15).

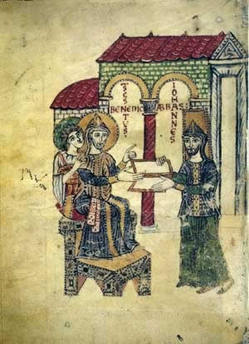

To live no longer for themselves but for Christ: this is what gives full meaning to the lives of those that let themselves be conquered by him. The human and spiritual journey of St. Benedict attests to this clearly, he who, leaving all things behind, dedicated himself to the faithful following of Jesus. Embodying in his own life the reality of the Gospel, he has become the founder of a vast movement of spiritual and cultural renaissance in the West. I would now like to refer to an extraordinary event of his life, which the biographer St. Gregory the Great relates, and with which you are certainly well acquainted. One could almost say that the holy patriarch was “lifted up” in an indescribable mystical experience. On the night of October 29 of the year 540 — reads the biography — and, facing the window, “with his eyes fixed on the stars he recollected himself in divine contemplation, the saint felt that his heart was inflamed … For him, the star filled firmament was like the embroidered curtain that revealed the Holy of Holies. At one point, he felt his soul felt itself carried to the other side of the veil, to contemplate the revealed face of him who dwells in inaccessible light” (cf. AI Schuster, History of Saint Benedict and his time, Ed Abbey Viboldone, Milan, 1965, p. 11 et seq.). Of course, similar to what happened to Paul after his heavenly rapture, St. Benedict, following this extraordinary spiritual experience, also found it necessary to start a new life. If the vision was transient, the effects were lasting, his very character — the biographers say — was changed, his appearance always remained calm and his behavior angelic, and even while he was living on earth, he understood that in his heart he was already in heaven.

St. Benedict received this gift of God not to satisfy his intellectual curiosity, but rather because the charism with which God had endowed him had the ability to reproduce in the monastery the very life of heaven and reestablish the harmony of creation through contemplation and work. Rightly, therefore, the Church venerates him as an “eminent teacher of the monastic life” and “doctor of spiritual wisdom in the love of prayer and work; shining guide of people in the light of the Gospel” who,”raised to heaven by a luminous road” teaches people of all ages to seek God and the eternal riches prepared by him (cf. Preface of the Holy in the monastery to the MR, 1980, 153).

Yes, Benedict was a shining example of holiness and pointed the monks to Christ as their only great ideal; he was a master of civility, who proposed a balanced and adequate vision of the demands of God and of the final ends of man; he also always kept well in mind the needs and the reasons of the heart, in order to teach and inspire a genuine and constant brotherhood, so that in the complexity of social relationships the unity of spirit capable of always building and maintaining peace was never lost sight of. It is not by

chance that the word Pax [peace] is the word that welcomes pilgrims and visitors at the gates of the abbey, rebuilt after the terrible disaster of the Second World War, which stands as a silent reminder to reject all forms of violence in order to build peace: in families, within communities, between peoples and all of humanity. St. Benedict invites every person that climbs this mountain to seek peace and follow it: “inquire pacem et sequere eam” [seek peace and follow it.] (Ps. 33,14-15) (Rule, Prologue, 17).

By its example, monasteries have become, over the centuries, centers of fervent dialogue, encounter and beneficial union of diverse peoples, unified by the evangelical culture of peace. The monks have known how to teach by word and example the art of peace, implementing in a concrete way the three “ties” that Benedict identifies as necessary to maintain the unity of the Spirit among men: the cross, which is the very law of Christ, the book which is culture, and the plow, which indicates work, the lordship over matter and time. Thanks to the activity of the monastery, articulated in the three-fold daily commitments of prayer, study and work, entire populations of Europe have experienced a genuine redemption and a beneficial moral, spiritual and cultural development, learning in the spirit of continuity with the past, of concrete action for the common good, and of openness to God and the transcendent aspect of the world. We pray that Europe always exploit this wealth of principles and Christian ideals, which constitutes an immense cultural and spiritual wealth.

This is possible but only if the constant teaching of St.

Benedict is embraced, the “quaerere Deum,” to seek God, as the fundamental commitment of man. Human beings cannot achieve full self-realization or ever be truly happy without God. It is your special responsibility, dear monks, to be living examples of this interior and profound relationship with him, implementing without compromise the program that your founder summarized in the “nihil amori Christi praeponere” [put nothing before the love of Christ.] (Rule 4.21). In this holiness consists, a valid proposal for every Christian, more than ever in our time, in which the need to anchor life and history to solid spiritual principles is felt.

Therefore, dear brothers and sisters, your vocation is a timely as ever, and your mission as monks is indispensable.

From this place, where his mortal remains rest, the patron saint of Europe continues to urge everyone to continue his work of evangelization and human promotion. I encourage you in the first place, dear brethren, to remain faithful to the spirit of your origins and to be authentic interpreters of this program of social and spiritual rebirth. The Lord grants you this gift, through the intercession of your holy founder, of his holy sister St. Scholastica, and of the saints of your order. And may the heavenly Mother of the Lord, who today we invoke as “Help of Christians,” watch over you and protect this abbey and all your monasteries, as well as the diocesan community that lives around Monte Cassino. Amen!

Pope Benedict XVI

Homily at Vespers II

The Abbey of Monte Casino

May 24, 2009