Most English language readers know little about the person and work of Luigi Giussani.

His vast publications have been virtually unknown in the philosophical or theological academy here in North America. The general public who are well read on religious topics have perhaps heard his name and associate it with a large Catholic lay movement known as “CL.” It would be useful, therefore, to begin with a general introduction to Luigi Giussani: the man, the priest, the professor, and the vibrant leader of a great apostolic movement in the Catholic Church today.

His vast publications have been virtually unknown in the philosophical or theological academy here in North America. The general public who are well read on religious topics have perhaps heard his name and associate it with a large Catholic lay movement known as “CL.” It would be useful, therefore, to begin with a general introduction to Luigi Giussani: the man, the priest, the professor, and the vibrant leader of a great apostolic movement in the Catholic Church today.

Luigi Giussani has devoted his life and priestly ministry to the evangelization and catechesis of young people for nearly 50 years. In the early days of his priesthood, while serving as seminary professor in the diocese of Milan in 1952, Giussani encountered some Italian High School students while on a train trip. At this time, many in the Church took it for granted that the Catholic faith was still firmly rooted in the mentality of the Italian people, and that its transmission to the next generation was no great cause for concern. Based on his brief conversation with a group of teenagers, however, Giussani intuited a profound problem which would soon manifest itself to the world in the intellectual and cultural revolutions of the 1960s. What he saw was this: not only did these young people have a poor grasp of the basic truths of the Catholic faith; they were unable to conceive the relationship between this Faith–which they still openly professed at that time–and their way of looking at the world, their way of making judgments about circumstances and events, their way of evaluating (i.e., assessing the real value) of the situations they had to deal with in life. The student might profess to be Catholic, recite the creed, and perhaps even know parts of his Catechism (or even more, if he was bright). But when it came to making judgments and decisions about things that he viewed as truly important to his life, his ideals and hopes for happiness were shaped by a secularized mentality; a mentality in which Christ and His Church were largely absent, or at best relegated to a dusty corner. Giussani saw that many of the young people in Italy in the early 1950s who would have described themselves as “Catholic” did not in fact seek to judge the realities of the world and the significance of their own lives according to a Christian mentality; that is, the “transformed and renewed mind” that St. Paul says is the basis for viewing the world in union with Christ and according to the wisdom of God’s plan (see Rom. 12:2).2 Rather, the mentality of these “young Catholics” was being shaped by all the contradictory emphases of the so-called “modern” era: the absolute sufficiency of “scientific” human reason on the one hand, and the exaltation of subjectivism on the other; the emphasis on a deontological ethics of duty divorced from the good of the person on the one hand, and the enthrallment with the spontaneity of mere instinct and emotional individualism on the other.

Giussani perceived the need for young people to receive an integral catechesis that would

help them to realize–both existentially and intellectually–that Christ is the center of all of life, and that because of this their experience of life in union with Christ in His Church should shape their entire outlook and invest all of their daily activity with an evangelical energy. Giussani therefore requested and received from his bishop permission to leave seminary teaching and inaugurate an educational apostolate for youth: first at the Berchet High School in Milan, and then for many years as Professor of religion at the Catholic University of Milan.

help them to realize–both existentially and intellectually–that Christ is the center of all of life, and that because of this their experience of life in union with Christ in His Church should shape their entire outlook and invest all of their daily activity with an evangelical energy. Giussani therefore requested and received from his bishop permission to leave seminary teaching and inaugurate an educational apostolate for youth: first at the Berchet High School in Milan, and then for many years as Professor of religion at the Catholic University of Milan.

Giussani’s teaching method was to challenge the oppressive secularism that dominated the mentality of his students by inspiring them to conduct a rigorous examination of themselves, the fundamental experiences that characterize man’s life and aspirations, and the radical incapacity of modern secular culture to do justice to the deep mystery of the human heart. This examination–carried out within an existentially vital ecclesial context in which Christ is encountered through a friendship with those who follow Him–leads to a rediscovery of man’s “religious sense,” that is, the fundamentally religious character of the questions and desires that are inscribed on his heart. Man has been made for God, and the only way that he can realize the truth of himself (and thus be happy) is by recognizing God and adhering to Him wholeheartedly. Giussani then sought to lead his students to understand and appreciate in a deeper way the fact that God has made this adherence to Himself concretely possible, attractive, and beautiful by becoming man and perpetuating His incarnate presence in the world through His Church.

Soon after he began teaching young people, Giussani founded an Italian Catholic student organization, Gioventu Studentesca. During the turmoil of the late 1960s, when almost all the Italian universities were taken over by Marxism or other radical left ideologies, Giussani’s students published a manifesto entitled Comunione e Liberazione, in which they declared that man can truly be free only if he lives in communion with Christ and the Church. Thus the group came to be known as “CL.” And when these students graduated from the university, they began to bring the educational methods of Giussani into the

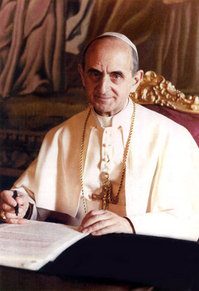

various places where they worked and lived their adult lives, continuing to learn from and to retain contact with one another and with their great teacher. By means of this friendship guided by Giussani’s particular pedagogical approach, a “movement”– a style of living the Catholic faith–took form. This “movement” gained the attention of other Italian bishops, priests, and people throughout the Church and even outside the Church. In this way, CL–while retaining its fundamentally theological and pedagogical character–moved far beyond the walls of the University of Milan. In 1982, Pope John Paul II called upon the members of CL to “Go into all the world and bring the truth, the beauty, and the peace which are found in Christ the Redeemer…

various places where they worked and lived their adult lives, continuing to learn from and to retain contact with one another and with their great teacher. By means of this friendship guided by Giussani’s particular pedagogical approach, a “movement”– a style of living the Catholic faith–took form. This “movement” gained the attention of other Italian bishops, priests, and people throughout the Church and even outside the Church. In this way, CL–while retaining its fundamentally theological and pedagogical character–moved far beyond the walls of the University of Milan. In 1982, Pope John Paul II called upon the members of CL to “Go into all the world and bring the truth, the beauty, and the peace which are found in Christ the Redeemer…

This is the charge I leave with you today.” The Pope made it clear that it was his desire that CL become an instrument of the new evangelization not only in Italy, but throughout the world. Following this desire of the Pope, numerous missionary initiatives were taken, and a more profound and stable presence of CL has since been established in Africa, the Americas, and other parts of Europe.

Today, CL is one of the largest “Ecclesial Movements” in the Church, counting among its 100,000 members around the world not only university students, but also bishops, priests, and lay people engaged in a variety of professions and cultural activities.

This an excerpt of the essay, Man in the Presence of Mystery. The author, John Janaro, professor of theology at Christendom College, delivered this paper in 1998.