The Christian event is the answer to the demand for the infinite which is the heart of man. So that man may walk along: “homo viator,” a man who draws near by the movement that has been put into him, that has been brought forth in him by the Mystery which makes all things and of

which he is made aware by the encounter, the encounters of life.

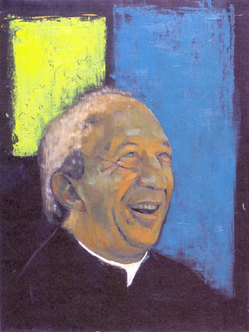

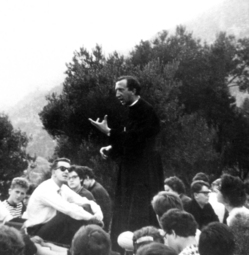

Category: Luigi Giussani

Keeping the centrality of Christ

Monsignor Giussani, with his fearless and unfailing

faith, knew that, even in this situation, Christ, the encounter with Him,

remains central, because whoever does not give God, gives too little, and

whoever does not give God, whoever does not make people find God in the Fact of

Christ, does not build, but destroys, because he gets human activity lost in

ideological and false dogmatisms. Fr Giussani kept the centrality of Christ

and, exactly in this way, with social works, with necessary service, he helped mankind

in this difficult world, where the responsibility of Christians for the poor in

the world is enormous and urgent.

Is Christ missing, or is it our humanity?

If Christ has nothing to do with what you touch and look at it, it’s not true that you are touching, it’s not true that you are looking. It’s not true that he has nothing to do with these things; rather, what’s true is that you’re not looking, touching, loving – your humanity isn’t true. In fact, you’re confused about your destiny and you’re completely skeptical about the possibility of reaching your destiny. What is human is missing: in our doubt, it’s not Christ that is missing, but rather our humanity. Msgr. Luigi Giussani

Luigi Giussani revealed

Sandro Magister’s recent essay, “The Mystery of Fr. Giussani, Revealed By His Writings” is a review of a recently published spiritual biography of Msgr. Luigi Giussani. The biography is still in Italian at the moment but there is an extract from Chapter 6 of Fr. Camisasca’s book illustrating the thought of Fr. Giussani. Read Magister’s article…

Father Luigi Giussani: 4th anniversary of reposing in the Lord

Christ and the Church: here is the synthesis of Monsignor Giussani’s life and of his apostolate. Without ever separating one from the other, he communicated around him a true love for the Lord and for the various Popes that he knew personally. He also had a great attachment for his Diocese and for his Pastors.

Pope John Paul II

May Father Giussani’s memory be eternal!

Father Giussani really wanted not to have his life for himself, but he gave life, and exactly in this way found life not only for himself, but for many others. He practised what we heard in the Gospel: he did not want to be served but to served, he was a faithful servant of the Gospel, he gave out all the wealth of his heart, he gave out all the divine wealth of the Gospel, with which he was penetrated and, serving in this way, giving his life, this life of his gave rich fruit–as we see in this moment–he has become really father of many and, having led people not to himself, but to Christ, he really won hearts, he has helped to make the world better and to open the world’s doors for heaven.

Pope Benedict XVI

Community of spirit in Saint Benedict, Don Luigi Giussani & Pope Benedict XVI

On this the feast of the great Saint Scholastica, the twin sister of Saint Benedict, I thought it would be appropriate to hear a few words about the significant connection between the Benedictines (Sts Benedict & Scholastica and Pope Benedict) and Father Luigi Giussani.

On this the feast of the great Saint Scholastica, the twin sister of Saint Benedict, I thought it would be appropriate to hear a few words about the significant connection between the Benedictines (Sts Benedict & Scholastica and Pope Benedict) and Father Luigi Giussani.

Signs of spiritual friendship

by Don Giacomo Tantardini (In 30 Days, May 2005)

…The hundredfold is not the outcome of a project, of a program. My real program of government is that of not doing my own will, of not following my own ideas, but of setting myself to listen, with the whole Church, to the word and will of the Lord and let myself be led by Him, so that it is He Himself who leads the Church in this hour of our history, Benedict XVI said again in the sermon of the mass opening his ministry. The hundredfold here below, like the eternal life, has a beginning, a “permanent” source (each word from the first appearance of Benedict XVI in St Peter’s Square, that was packed with Romans hurrying to see the new Pope, remains in the memory: Trusting in his permanent help). The permanent beginning is Jesus Christ, the Lord risen.

The Church is living because Christ is living, because he is truly risen (Easter Sunday 24 April). And on Sunday 1 May, when, addressing the Churches of the East which were celebrating Easter, he repeated with force Christós anesti! Yes, Christ is risen, is truly risen!, the immediate applause that rose from the square packed with faithful up to that window was very fine.

Here the communion of mind and heart among Saint Benedict, Benedict XVI, Don Giussani and the most ordinary believer is luminous and total.

Don Giussani always kept the gaze of his life and heart fixed on Christ (Cardinal Ratzinger, in Milan Cathedral, at Don Guissani’s funeral). We need men who keep their eyes looking at God, learning from there true humanity (in Subiaco). And, again in Subiaco, Cardinal Ratzinger concluded his lecture by quoting the more beautiful phrase that Saint Benedict repeats twice in the Rule: Put absolutely nothing before Christ who can lead us all to eternal life. Here, chapter 72: Christo omnino nihil praeponant. In chapter 4: Nihil amori Christi praeponere/ put nothing before the love of Christ.

Don Giussani always kept the gaze of his life and heart fixed on Christ (Cardinal Ratzinger, in Milan Cathedral, at Don Guissani’s funeral). We need men who keep their eyes looking at God, learning from there true humanity (in Subiaco). And, again in Subiaco, Cardinal Ratzinger concluded his lecture by quoting the more beautiful phrase that Saint Benedict repeats twice in the Rule: Put absolutely nothing before Christ who can lead us all to eternal life. Here, chapter 72: Christo omnino nihil praeponant. In chapter 4: Nihil amori Christi praeponere/ put nothing before the love of Christ.

Experience: the capacity to comprehend & love in the thought of Luigi Giussani

Experience

In 1963, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, (later Pope Paul VI, wrote a letter to Fr Giussani in which he raised some questions about the primacy given to experience in the high school youth group Gioventù Studentesca (cf M Camisasca, Comunione e Liberazione. Le origini [Communion and Liberation. The origins], San Paolo, 2001). Father Giussani answered the questions in a booklet entitled precisely L’esperienza (Experience) in November 1963. In August 1964, Pope Paul VI wrote in his encyclical Ecclesiam suam: “The mystery of the Church is not a truth to be confined to the realms of speculative theology. It must be lived, so that the faithful may have a kind of intuitive experience of it, even before they come to understand it clearly” (no 37).

In 1963, Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, (later Pope Paul VI, wrote a letter to Fr Giussani in which he raised some questions about the primacy given to experience in the high school youth group Gioventù Studentesca (cf M Camisasca, Comunione e Liberazione. Le origini [Communion and Liberation. The origins], San Paolo, 2001). Father Giussani answered the questions in a booklet entitled precisely L’esperienza (Experience) in November 1963. In August 1964, Pope Paul VI wrote in his encyclical Ecclesiam suam: “The mystery of the Church is not a truth to be confined to the realms of speculative theology. It must be lived, so that the faithful may have a kind of intuitive experience of it, even before they come to understand it clearly” (no 37).

At the beginning of the history of the Movement, the method that was developed to sustain the proposal for living the charism, which is Communion and Liberation, was precisely defined, furnishing a very valuable tool for living the present in greater awareness, a present that is so full of risk because of the ever-recurring danger of reducing experience to sentimentalism or moralism, especially at a time when everything seems to end up in nothingness out of a widespread insecurity. This is the complete opposite of the certitude that arises from the encounter with Christ. It is for this reason that some of Giussani’s ideas on

Experience are offered here (which later became a chapter of The Risk of Education).

Experience as the Development of the Person

There was a time when the person did not exist, hence what constitutes the person is a given; it is the product of another.

This original condition is repeated at all levels of the person’s development. The cause of my growth does not coincide with me, but is other than me.

Concretely, experience means to live what causes me to grow.

A person grows as a result of experience; that is, the valorization of an objective relationship.

Nota Bene: “Experience” connotes the fact of becoming aware of one’s growth, in two basic aspects: the capacity to comprehend and the capacity to love.

a) A person is first of all consciousness, a being that is aware. It follows that experience is not the doing or the setting up of relationships with reality in a mechanical way. This is the mistake implied in the phrase “to have an experience,” where “experience” becomes synonymous with “trying something out.”

What characterizes experience is our understanding something, discovering its meaning. To have an experience means to comprehend the meaning of something. This is done by discovering its link to everything else; thus experience means also to discover the purpose of a given thing and its function in the world.

b) It is also true, however, that we are not the creators of meaning. The connection that binds something to everything else is an objective one. Therefore, true experience involves saying yes to a situation that attracts us; it means appropriating what is being said to us. It is composed of making things our own, but in such a way that we proceed within their objective meaning, which is the Word of an Other.

True experience mobilizes and increases our capacity to accept and to love. True experience throws us into the rhythms of the real, drawing us irresistibly toward our union with the ultimate aspect of things and their true, definitive meaning.

Nature as the Place of Experience

We give the name “nature” to the place where those objective relationships that develop a person take place: nature is the locus of experience.

Characteristically, nature weaves an organized, multi-leveled fabric that awakens the need for unity immanent in each one of us.

This fundamental need finds a correspondence in our affirmation of God, for God is precisely the unitary meaning which nature’s objective and organic structure calls the human consciousness to recognize.

Error in Human Experience

The need for unity that animates the conscious life of the person must struggle against divisive forces present in humanity, forces that drive him to disregard objective connections and to tear apart the organic structure of nature’s tapestry, isolating each single aspect of it.

Because of the human being’s need for unity, isolating each relationship or aspect inevitably turns each relationship into an absolute. All of this blocks the dynamic, evolutionary relationship of the person with reality, creating a series of disjointed pieces that are abnormally affirmed.

This tendency to separate and isolate gives all sorts of typical and inadequate connotations to the word experience, among which are an immediate reaction to things, the multiplication of links through the mere proliferation of initiatives, a sudden attraction or disgust for the new, an insistence on our own designs or plans, insisting on memories of the past that have no value in the present, or even referring to a particular event in order to block aspirations or stunt ideals.

God’s Mystery Revealed in the Field of Human Experience

The role of Christ and the prophets in history was to announce with absolute clarity that God is the ultimate implication of human experience, and that therefore the religious sense is an inevitable dimension of an authentic, exhaustive experience.

But Christ’s exceptional nature does not lie so much in the fact that His presence calls us to acknowledge that implication as in the fact that His very coming constitutes the physical presence of the ultimate meaning of history.

There cannot be an exhaustive, full, human experience without the valuation, whether conscious or not, of its relation with the event of Christ-Man.

The objective relationship that we spoke of earlier which fulfills the person no longer takes place only in nature, for with the advent of Jesus there is also a “super-natural” place; its development is in the Church, the Mystical Body of Christ.

Christian Experience

The Christian experience and that of the Church are one, single, vital act, in which a triple factor is at work, as follows:

a) An encounter with an objective fact which has an origin independent of the person having the experience. The existential reality of this fact or event is a community that can be documented, like every reality which is fully human. This community has an authority expressed through a human voice in judgments and directives, constituting criteria and meaning.

All forms of Christian experience, even those lived in the innermost recesses of the soul, refer in some way to an encounter with the community and to its authority.

b) The ability to properly perceive the meaning of that encounter. The value of the fact which we encounter transcends our power to understand so much so that an act of God is required for an adequate understanding. The same gesture by which God makes His presence known to humanity in the Christian event also enhances a person’s potential for knowledge, raising him up to the exceptional reality to which God attracts him. We call this the grace of faith.

c) An awareness of the correspondence between the meaning of the fact that we encounter and the meaning of our own existence, between the reality of Christ and the Church and the reality of our own person, between the encounter and our own destiny. It is the awareness of this correspondence that brings about the growth of the self, an essential component of experience.

Above all, in the Christian experience one sees clearly that in an authentic experience, human self-consciousness and capacity for criticism are engaged, and that this is very different from a mere impression or a sentimental echo.

It is within this verification of Christian experience that the mystery of the divine initiative exalts human reason. Freedom is at work in this verification. We cannot register or recognize the glorious correspondence between the presence of the mystery and our dynamism as human beings unless we have first accepted and are fully aware of our own radical dependence, of the fact that we are “made.” This awareness constitutes our simplicity, purity of heart, the poverty of spirit.

The drama of our freedom is entirely contained in this poverty of spirit, a drama so deep that when it happens, it is nearly hidden.

Faith, Always a New Act

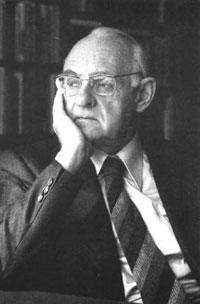

This 1995 essay by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) is a marvelous piece to meditate on today. Faith and communion, freedom and personal integration in God are relevant topics in our era where there is a lack of understanding of the basics of Christian faith. Without mentioning his name and his work, the author points to Msgr. Giussani’s Communion and Liberation and other ecclesial movements.

Let me begin with a brief story from the early postconciliar period. The Council documents – particularly the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, but also the decrees on ecumenism, on mission, on non-Christian religions, and on freedom of religion – had opened up broad vistas of dialogue for the Church and theology. New issues were appearing on the horizon, and it was becoming necessary to find new methods. It seemed self-evident that a theologian who wanted to be up to date and who rightly understood his task should temporarily suspend the old discussions and devote all of his energies to the new questions pressing in from every side.

At about this time, I sent a small piece of mine to Hans Urs von Balthasar. Balthasar

replied by return mail on a correspondence card, as he always did, and, after expressing his thanks, added a terse sentence that made an indelible impression on me: Do not presuppose the faith but propose it. This was an imperative that hit home. Wide-ranging exploration of new fields was good and necessary, but only so long as it issued from, and was sustained by, the central light of faith.

replied by return mail on a correspondence card, as he always did, and, after expressing his thanks, added a terse sentence that made an indelible impression on me: Do not presuppose the faith but propose it. This was an imperative that hit home. Wide-ranging exploration of new fields was good and necessary, but only so long as it issued from, and was sustained by, the central light of faith.

Faith is not maintained automatically. It is not a “finished business” that we can simply take for granted. The life of faith has to be constantly renewed. And since faith is an act that comprehends all the dimensions of our existence, it also requires constantly renewed reflection and witness. It follows that the chief points of faith – God, Christ, the Holy Spirit, grace and sin, sacraments and Church, death and eternal life -are never outmoded. They are always the issues that affect us most profoundly. They must be the permanent center of preaching and therefore of theological reflection. The bishops present at the 1985 Synod called for a universal catechism of the whole Church because they sensed precisely what Balthasar had put into words in his note to me. Their experience as shepherds had shown them that the various new pastoral activities have no solid basis unless they are irradiations and applications of the message of faith. Faith cannot be presupposed; it must be proposed. This is the purpose of the Catechism. It aims to propose the faith in its fullness and wealth, but also in its unity and simplicity.

What does the Church believe? This question implies another: Who believes, and how does someone believe? The Catechism treats these two main questions, which concern, respectively, the “what” and the “who” of faith, as an intrinsic unity. Expressed in other terms, the Catechism displays the act of faith and the content of faith in their indivisible unity. This may sound somewhat abstract, so let us try to unfold a bit what it means. We find in the creeds two formulas: “I believe” and “We believe.” We speak of the faith of the Church, of the personal character of faith and finally of faith as a gift of God, as a “theological act”, as contemporary theology likes to put it. What does all of this mean?

Faith is an orientation of our existence as a whole. It is a fundamental option that affects every domain of our existence. Nor can it be realized unless all the energies of our existence go into maintaining it. Faith is not a merely intellectual, or merely volitional, or merely emotional activity -it is all of these things together. It is an act of the whole self, of the whole person in his concentrated unity. The Bible describes faith in this sense as an act of the “heart” [Romans 10:9].

Faith is a supremely personal act. But precisely because it is supremely personal, it

transcends the self, the limits of the individual. Augustine remarks that nothing is so little ours as our self. Where man as a whole comes into play, he transcends himself; an act of the whole self is at the same time always an opening to others, hence, an act of being together with others (Mitsein). What is more, we cannot perform this act without touching our deepest ground, the living God who is present in the depths of our existence as its sustaining foundation.

transcends the self, the limits of the individual. Augustine remarks that nothing is so little ours as our self. Where man as a whole comes into play, he transcends himself; an act of the whole self is at the same time always an opening to others, hence, an act of being together with others (Mitsein). What is more, we cannot perform this act without touching our deepest ground, the living God who is present in the depths of our existence as its sustaining foundation.

Any act that involves the whole man also involves, not just the self, but the we-dimension, indeed, the wholly other “Thou”, God, together with the self. But this also means that such an act transcends the reach of what I can do alone. Since man is a created being, the deepest truth about him is never just action but always passion as well; man is not only a giver but also a receiver. The Catechism expresses this point in the following words: “No one can believe alone, just as no one can live alone. You have not given yourself faith as you have not given yourself life.” Paul’s description of his experience of conversion and baptism alludes to faith’s radical character: “It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me” [Galatians 2,20]. Faith is a perishing of the mere self and precisely thus a resurrection of the true self. To believe is to become oneself through liberation from the mere self, a liberation that brings us into communion with God mediated by communion with Christ.

So far, we have attempted, with the help of the Catechism, to analyze “who” believes, hence, to identify the structure of the act of faith. But in so doing we have already caught sight of the outlines of the essential content of faith. In its core, Christian faith is an encounter with the living God. God is, in the proper and ultimate sense, the content of our faith. Looked at in this way, the content of faith is absolutely simple: I believe in God. But this absolute simplicity is also absolutely deep and encompassing. We can believe in God because he can touch us, because he is in us, and because he also comes to us from the outside. We can believe in him because of the one whom he has sent “Because he has ‘seen the Father,’ ” says the Catechism, referring to John 6:56, “Jesus Christ is the only one who knows him and can reveal him”. We could say that to believe is to be granted a share in Jesus’ vision. He lets us see with him in faith what he has seen.

This statement implies both the divinity of Jesus Christ and his humanity. Because Jesus is the Son, he has an unceasing vision of the Father. Because he is man, we can share this vision. Because he is both God and man at once, he is neither merely a historical person nor simply removed from all time in eternity. Rather, he is in the midst of time, always alive, always present.

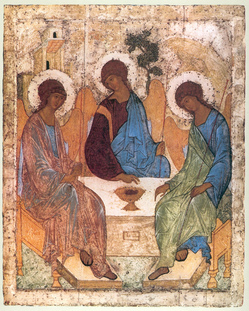

But in saying this, we also touch upon the mystery of the Trinity. The Lord becomes present to us through the Holy Spirit. Let us listen once more to the Catechism: “One cannot believe in Jesus Christ without sharing in his Spirit . . . Only God knows God completely: we believe in the Holy Spirit because he is God.” It follows from what we have said that, when we see the act of faith correctly, the single articles of faith unfold by themselves. God becomes concrete for us in Christ. This has two consequences. On the one hand, the triune mystery of God becomes discernible; on the other hand, we see that God has involved himself in history to the point that the Son has become man and now sends us the Spirit from the Father. But the Incarnation also includes the mystery of the Church, for Christ came to “gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad” [John 1:52]. The “we” of the Church is the new communion into which God draws us beyond our narrow selves [cf. John 12:32]. The Church is thus contained in the first movement of the act of faith itself. The Church is not an institution extrinsically added to faith as an organizational frame work for the common activities of believers. No, she is integral to the act of faith itself The “I believe” is always also a “We believe.” As the Catechism says, “‘I believe’ is also the Church, our mother, responding to God by faith as she teaches us to say both ‘I believe’ a ‘We believe.'” We observed just now that the analysis of the act of faith immediately displays faith’s essential content as well: faith is a response to the triune God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. We can now add that the same act of faith also embraces God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ, his theandric mystery, and thus the entirety of salvation history. It further becomes clear that the People of God, the Church as the human protagonist of salvation history, is present in the very act of faith. It would not be difficult to demonstrate in a similar fashion that the other items of belief are also explications of the one fundamental act of encountering the living God. For by its very nature, relation to God has to do with eternal life. And this relation necessarily transcends the merely human sphere. God is truly God on1y if he is the Lord of all things. And he is the Lord of all things oo1y if he is their Creator. Creation, salvation history and eternal life are thus themes that flow directly from the question of God. In addition, when we speak of God’s history with man, we also imply the issue of sin and grace. We touch upon the question of how we encounter God, hence, the question of the liturgy, of the sacraments, of prayer and morality.

But in saying this, we also touch upon the mystery of the Trinity. The Lord becomes present to us through the Holy Spirit. Let us listen once more to the Catechism: “One cannot believe in Jesus Christ without sharing in his Spirit . . . Only God knows God completely: we believe in the Holy Spirit because he is God.” It follows from what we have said that, when we see the act of faith correctly, the single articles of faith unfold by themselves. God becomes concrete for us in Christ. This has two consequences. On the one hand, the triune mystery of God becomes discernible; on the other hand, we see that God has involved himself in history to the point that the Son has become man and now sends us the Spirit from the Father. But the Incarnation also includes the mystery of the Church, for Christ came to “gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad” [John 1:52]. The “we” of the Church is the new communion into which God draws us beyond our narrow selves [cf. John 12:32]. The Church is thus contained in the first movement of the act of faith itself. The Church is not an institution extrinsically added to faith as an organizational frame work for the common activities of believers. No, she is integral to the act of faith itself The “I believe” is always also a “We believe.” As the Catechism says, “‘I believe’ is also the Church, our mother, responding to God by faith as she teaches us to say both ‘I believe’ a ‘We believe.'” We observed just now that the analysis of the act of faith immediately displays faith’s essential content as well: faith is a response to the triune God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. We can now add that the same act of faith also embraces God’s incarnation in Jesus Christ, his theandric mystery, and thus the entirety of salvation history. It further becomes clear that the People of God, the Church as the human protagonist of salvation history, is present in the very act of faith. It would not be difficult to demonstrate in a similar fashion that the other items of belief are also explications of the one fundamental act of encountering the living God. For by its very nature, relation to God has to do with eternal life. And this relation necessarily transcends the merely human sphere. God is truly God on1y if he is the Lord of all things. And he is the Lord of all things oo1y if he is their Creator. Creation, salvation history and eternal life are thus themes that flow directly from the question of God. In addition, when we speak of God’s history with man, we also imply the issue of sin and grace. We touch upon the question of how we encounter God, hence, the question of the liturgy, of the sacraments, of prayer and morality.

But I do not want to develop all of these points in detail now; my chief concern has been precisely to get a glimpse of the intrinsic unity of faith, which is not a multitude of propositions but a full and simple act whose simplicity contains the whole depth and breadth of being. He who speaks of God, speaks of the whole; he learns to discern the essential from the inessential, and he comes to know, albeit oo1y fragmentarily and “in a glass, darkly” [I Corinthians 13:12] as long as faith is faith and not yet vision, something of the inner logic and unity of all reality.

Finally, I would like to touch briefly on the question we mentioned at the beginning of our reflections. I mean the question of how we believe. Paul furnishes us with a remarkable and extremely helpful statement on this matter when he says that faith is an obedience “from the heart to the form of doctrine into which you were handed over” [Romans 6:17]. These words ultimately express the sacramental character of faith, the intrinsic connection between confession and sacrament. The Apostle says that a “form of doctrine” is an essential component of faith. We do not think up faith on our own. It does not come from us as an idea of ours but to us as a word from outside. It is, as it were, a word about the Word; we are “handed over” into this Word that reveals new paths to our reason and gives form to our life.

We are “handed over” into the Word that precedes us through an immersion in water symbolizing death. This recalls the words of Paul cited earlier: “I live, yet not I”‘; it reminds us that what takes place in the act of faith is the destruction and renewal of the self. Baptism as a symbolic death links this renewal to the death and Resurrection of Jesus Christ. To be handed over into the doctrine is to be handed over into Christ. We cannot receive his word as a theory in the same way that we learn, say, mathematical formulas or philosophical opinions. We can learn it only in accepting a share in Christ’s destiny. But we can become sharers in Christ’s destiny only where he has permanently committed himself to sharing in man’s destiny: in the Church. In the language of this Church we call this event a “sacrament”. The act of faith is unthinkable. without the sacramental component.

These remarks enable us to understand the concrete literary structure of the Catechism. To believe, as we have heard, is to be handed over into a form of doctrine. In another passage, Paul calls this form of doctrine a confession [cf. Romans 10:9]. A further aspect of the faith-event thus emerges. That is, the faith that comes to us as a word must also become a word in us, a word that is simultaneously the expression of our life. To believe is always also to confess the faith. Faith is not private but something public that concerns the community. The word of faith first enters the mind, but it cannot stay there: thought must always become word and deed again. The Catechism refers to the various kinds of confessions of faith that exist in the Church: baptismal confessions, conciliar confessions, confessions formulated by popes.

Each of these confessions has a significance of its own. But the primordial type that serves as a basis for all further developments is the baptismal creed. When we talk about catechesis, that is, initiation into the faith and adaptation of our existence to the Church’s communion of faith, we must begin with the baptismal creed. This has been true since apostolic times and therefore imposed itself as the method of the Catechism, which, in fact, unfolds the contents of faith from the baptismal creed. It thus becomes apparent how the Catechism intends to teach the faith: catechesis is catechumenate. It is not merely religious instruction but the act whereby we surrender ourselves and are received into the word of faith and communion with Jesus Christ.

Adaptation to God’s ways is an essential part of catechesis. Saint Irenaeus says a propos of this that we must accustom ourselves to God, just as in the Incarnation God accustomed himself to us men. We must accustom ourselves to God’s ways so that we can learn to bear his presence in us. Expressed in theological terms, this means that the image of God – which is what makes us capable of communion of life with him – must be freed from its encasement of dross. The tradition compares this liberation to the activity of the sculptor who chisels away at the stone bit by bit until the form that he beholds emerges into visibility.

Catechesis should always be such a process of assimilation to God. After all, we can only know a reality if there is something in us corresponding to it. Goethe, alluding to Plotinus, says that “the eye could never recognize the sun were it not itself sunlike. The cognitional process is a process of assimilation, a vital process. The “we”, the “what” and the “how” of faith belong together.

This brings to light the moral dimension of the act of faith, which includes a style of humanity we do not produce by ourselves but that we gradually learn by plunging into our baptismal existence. The sacrament of penance is one such immersion into baptism, in which God again and again acts on us and draws us back to himself Morality is an integral component of Christianity, but this morality is always part of the sacramental event of “Christianization” (Christwerdung) an event in which we are not the sole agents but are always, indeed, primarily, receivers. And this reception entails transformation.

The Catechism therefore cannot be accused of any fanciful attachment to the past when it unfolds the contents of faith using the baptismal creed of the Church of Rome, the so-called “Apostles’ Creed”. Rather, this option brings to the fore the authentic core of the act of faith and thus of catechesis as existential training in existence with God.

Equally apparent is that the Catechism is wholly structured according to the principle of the hierarchy of truths as understood by the Second Vatican Council. For, as we have seen, the creed is in the first instance a confession of faith in the triune God developed from, and bound to, the baptismal formula. All of the “truths of faith” are explications of the one truth that we discover in them. And this one truth is the pearl of great price that is worth staking our lives on: God. He alone can be the pearl for which we give everything else. Dio solo basta, he who finds God has found all things. But we can find him only because he has first sought and found us. He is the one who acts first, and for this reason faith in God is inseparable from the mystery of the Incarnation, of the Church and of the sacraments. Everything that is said in the Catechism is an unfolding of the one truth that is God himself – the “love that moves the sun and all the stars”.

[From Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger – Benedict XVI, Gospel, Catechesis, Catechism. Sidelights on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 1977, pp. 23-34. Original title: Evangelium, Katechese, Katechismus. Streiflichter auf den Katechismus der katholischen Kirche ©Verlag Neue Stadt 1995.

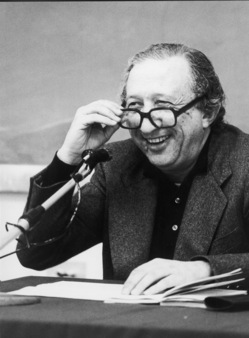

What is Luigi Giussani’s Contribution To Theology? Part II: Nothing less than the Infinite

[Part I]

Man wants happiness by nature. I want happiness. So I go out and buy a car. The car

gives me a taste of happiness but does not fully satisfy the desire. So my desire becomes a question: “What will make me truly and fully happy?” Or perhaps, after I have bought the car and am still enjoying the taste of partial happiness that it gives me, I get into an accident and wreck my beautiful new possession. My simple desire finds itself full of questions: “Why was I not able to hold onto that thing and the satisfaction it gave me? Why do I lose things? Why is life so fragile, and is there something that won’t let me down?”

gives me a taste of happiness but does not fully satisfy the desire. So my desire becomes a question: “What will make me truly and fully happy?” Or perhaps, after I have bought the car and am still enjoying the taste of partial happiness that it gives me, I get into an accident and wreck my beautiful new possession. My simple desire finds itself full of questions: “Why was I not able to hold onto that thing and the satisfaction it gave me? Why do I lose things? Why is life so fragile, and is there something that won’t let me down?”

The more we take our own selves and our actions seriously, the more we perceive the mysteriousness and also the urgency of these questions, the fact that we cannot really avoid them’, they are necessarily at the root of everything we do. This is because it is the nature of the human being to expect something, to look for fulfillment in everything he does. And where is the limit to this desire to be fulfilled? There is no limit. It is unlimited. Every achievement, every possession opens up on a further possibility, a depth that remains to be explored, a sense of incompleteness, a yearning for more. We are like hikers in the mountains (an analogy Giussani is fond of): we see a peak and we climb to the top. When we arrive there, we have a new view, and in the distance we see a higher peak promising a still greater vista.

In the novel The Second Coming by Walker Percy, the character of Allie–a mentally ill woman living alone in a greenhouse–expresses the mysterious depths of human desire through her difficulties in figuring out what to do at four o’clock in the afternoon: “If time is to be filled or spent by working, sleeping, eating, what do you do when you finish and there is time left over?”

Giussani quotes the great 19th century Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi–who is speaking here in the persona of a shepherd watching his flock by night, conversing with the moon:

Giussani quotes the great 19th century Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi–who is speaking here in the persona of a shepherd watching his flock by night, conversing with the moon:

And when I gaze upon you,

Who mutely stand above the desert plains

Which heaven with its far circle but confines,

Or often, when I see you

Following step by step my flock and me,

Or watch the stars that shine there in the sky,

Musing, I say within me:

“Wherefore those many lights,

That boundless atmosphere,

And infinite calm sky? And what the meaning

Of this vast solitude? And what am I?

There are a couple of points about this striking poetic excerpt that are worth mentioning as illustrative of central themes in Giussani. The first point is this: note that the shepherd’s questions are so poignantly expressed “from the heart” (Musing, I say within me). They are “personal” questions we might say; that is, they are questions that seem deeply important to the shepherd’s own life, that emerge from the shepherd’s solitude as he watches the flocks by night and gazes at the moon. And yet, the questions themselves are really “philosophical” questions: “metaphysical” questions which ask about the relationship of the universe to its mysterious Source, and “anthropological” questions about the nature of the world, of man, of the self. Let us note these things only to emphasize that Giussani’s evaluation of the dynamic of the human heart is not exclusively concerned with the pursuit of external objects and the way in which these objects lead “beyond” themselves the acting person who engages them. Giussani stresses that the need for truth is inscribed on the human heart; the need to see the meaning of things is fundamental to man. Hence the “objectivity” required for addressing philosophical and scientific questions does not imply that these questions are detached from the “heart” of the person who deals with them. When the scientist scans that infinite, calm sky and that vast solitude with his telescope, he must record what he sees, not what he wishes he would have seen. In this sense, he must be “objective,” and his questions and methodology must be detached from his own particular interests. But what puts him behind that telescope in the first place is his own personal need for truth and this need grows and articulates itself more and more as questions emerge in the light of his discoveries. All of this could be applied by analogy to the researches carried out by a true philosopher.

The second point is this: Leopardi’s poem conveys with imaginative force the inexhaustibility of human desire and the questions through which it is expressed, or at least tends to be expressed insofar as man is willing to live in a way that is true to himself (several chapters of Giussani’s book are devoted to the various ways in which man is capable of distracting himself or ignoring the dynamic of the religious sense, or anesthetizing himself against its felt urgency). Even more importantly, he indicates that the unlimited character of man’s most fundamental questions points toward an Infinite Mystery, a mystery that man continually stands in front of with fascination and existential hunger but also with questions, because he is ultimately unable by his own power to unveil its secrets.

The experience of life teaches man, if he is willing to pay attention to it, that what he is truly seeking, in every circumstance is the unfathomable mystery which alone corresponds to the depths of his soul. Offer to man anything less than the Infinite and you will frustrate him, whether he admits it or not. Yet at the same time man is not able to grasp the Infinite by his own power. Man’s power is limited, and anything it attains it finitizes, reducing it to the measure of itself. The desire of man as a person, however, is unlimited, which means that man does not have the power to completely satisfy himself; anything that he makes is going to be less than the Infinite.

Here we begin to see clearly why Giussani holds that the ultimate questions regarding the meaning, the value, and the purpose of life have a religious character; and how it is that these questions are asked by everyone within the ordinary, non-theoretical reasoning process which he terms “the religious sense.” The human heart is, in fact, a great, burning question, a plea, an insatiable hunger, a fascination and a desire for the unfathomable mystery that underlies reality and that gives life its meaning and value. This mystery is something Other than any of the limited things that we can perceive or produce; indeed it is their fundamental Source. Therefore, the all-encompassing and limitless search that constitutes the human heart and shapes our approach to everything is a religious search. It is indeed, as we shall see in a moment, a search for “God.”

We seek an infinite fulfillment, an infinite coherence, an infinite interpenetration of unity between persons, an infinite wisdom and comprehension, an infinite love, an infinite perfection. But we do not have the capacity to achieve any of these things by our own

power. Yet, in spite of this incapacity, in spite of the fact that the mystery of life–the mystery of happiness–seems always one step beyond us, our natural inclination is not one of despair, but rather one of dogged persistence and constant hope. Giussani insists that this hope and expectation is what most profoundly shapes the self; when I say the word “I,” I express this center of hope and expectation of infinite perfection and happiness that is coextensive with myself, that “is” myself, my heart. And when I say the word “you,” truly and with love, then I am acknowledging that same undying hope that shapes your self.

power. Yet, in spite of this incapacity, in spite of the fact that the mystery of life–the mystery of happiness–seems always one step beyond us, our natural inclination is not one of despair, but rather one of dogged persistence and constant hope. Giussani insists that this hope and expectation is what most profoundly shapes the self; when I say the word “I,” I express this center of hope and expectation of infinite perfection and happiness that is coextensive with myself, that “is” myself, my heart. And when I say the word “you,” truly and with love, then I am acknowledging that same undying hope that shapes your self.

The human person walks on the roads of life with his hands outstretched toward the mystery of existence, constantly pleading for the fulfillment he seeks–not in despair but

with hope– because the circumstances and events of life contain a promise, they whisper continually that happiness is possible. This is what gives the human spirit the strength to carry on even in the midst of the greatest difficulties.

with hope– because the circumstances and events of life contain a promise, they whisper continually that happiness is possible. This is what gives the human spirit the strength to carry on even in the midst of the greatest difficulties.

Let us note two further points. First of all: I cannot answer the ultimate questions about the meaning of my life, and yet every fiber of my being seeks that answer and expects it. There must be Another who does correspond to my heart, who can fill the need that I am. To deny the possibility of an answer is to uproot the very foundation of the human being and to render everything meaningless. As Macbeth says, it would be as if life is “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” There must be an answer; and a human being cannot live without seeking that answer. Giussani says that a human being cannot live five minutes without affirming something, consciously or unconsciously, that makes those five minutes worthwhile. This is the basic structure of human reason at its root. “Just as an eye, upon opening, discovers shapes and colors, so human reason–by engaging the problems and interests of life–seeks and affirms some ultimate” value and significance which gives meaning to everything. But if we are honest, if we realize that we cannot fulfill ourselves, if we face the fact that the answer to the question of the meaning of life is not something we can discover among our possessions, or measure or dominate or make with our own hands, then we begin to recognize that our need for happiness points to Someone Else, to an Infinite Someone who alone can give us what we seek.

Second: this longing of my heart, this seeking of the Infinite is not something I made up or chose for myself. It is not my idea or my project or my particular quirk. It corresponds to the way I am, to the way I “find myself independent of any of my personal preferences or decisions. It is at the root of me. It is at the root of every person. It is in fact given to me, and to every person–this desire for the Mystery that is at the origin of everything that I am and do. In the depths of my own self there is this hidden, insatiable hunger and thirst, this “heart that says of You, ‘seek His face!'” (Psalm 27:8), this need for an Other that suggests His presence at the origin of my being. He gives me my being; He is “nearer to me than I am to myself as St. Augustine says. And He has made me for Himself, He has placed within each of us a desire that goes through all the world in search of signs of His presence. In the depths of our being, we are not alone. We are made by Another and for Another. “You have made us for Yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in You,” says St. Augustine.

Thus, Giussani teaches that the Mystery of God is the only reality that corresponds to the “heart” of man: to the fundamental questions of human reason and the fundamental desire of the human freedom. It is this Infinite Mystery that the human person seeks in every circumstance of life. In our work, our loves, our friendships, our leisure time, our eating and drinking, our living and dying–in all of these activities we seek the face of the unfathomable Mystery that we refer to with poor words like “happiness” or “fulfillment” or “perfection.”

Thus, Giussani teaches that the Mystery of God is the only reality that corresponds to the “heart” of man: to the fundamental questions of human reason and the fundamental desire of the human freedom. It is this Infinite Mystery that the human person seeks in every circumstance of life. In our work, our loves, our friendships, our leisure time, our eating and drinking, our living and dying–in all of these activities we seek the face of the unfathomable Mystery that we refer to with poor words like “happiness” or “fulfillment” or “perfection.”

St. Thomas Aquinas says that God is happiness by His Essence, and we are called to participate in His happiness by being united to Him who is Infinite Goodness. We are made for happiness. By our very nature we seek happiness. To be religious, then, is to recognize that God alone can make us happy. It is to recognize the mysterious existential reflection of God’s infinite truth, goodness, and beauty that radiates from every creature, that lights up the circumstances of our lives, and calls out to us through all the opportunities that life presents to us.

In this sketch of Giussani’s understanding of what he calls “the religious sense,” we can see the profound reflections that underlie his great apostolate: his effort to teach his students that religion cannot be relegated to the fringes of life. Giussani insisted to his students that religion was not to be simply delineated as one aspect of life: a comfort for our sentiments, a list of ethical rules, a foundation for the stability of human social life (even though it entails such things as various consequences that follow from what it is in itself). Rather, the realm of the religious is coextensive with our happiness. The proper position of the human being is to live each moment asking for God to give him the happiness he seeks but cannot attain by his own power. Asking for true happiness–this is the true position of man in front of everything. Giussani often points out that “structurally” (that is, by nature), man is a “beggar” in front of the mystery of Being.

This brings us to the final chapters of The Religious Sense, in which Giussani analyses the dramatic character of this truth about man, both in terms of the very nature of this position of “being a beggar” and in terms of how this truth has played itself out in the great drama of human history. We could all too easily allow ourselves to be lulled to sleep by all of this lovely language about desiring the Infinite Mystery, and end up missing the point. The image of the beggar ought not to be romanticized in our imaginations. Generally people don’t like to be beggars, and they don’t have much respect for beggars. We should be able to attain what we need by our own efforts; is this not a basic aspect of man’s sense of his own dignity? And yet the very thing we need most is something that we do not have the power to attain, something we must beg for. This is the true human position, and yet it is not as easy to swallow as it may at first appear.

We are beggars in front of our own destiny because the Infinite One for whom our hearts have been made is always beyond the things of this world that point toward Him but do not allow us to extract His fullness from them by our own power. This fact causes a great tension in the experience of the human person–a “vertigo,” a dizziness, Giussani calls it –and there results the inevitable temptation to shrink the scope of our destiny, to attempt to be satisfied with something within our power, something we are capable of controlling and manipulating. This, says Giussani, is the essence of idolatry. Instead of allowing ourselves to be “aimed” by the beauty of things toward a position of poverty and begging in front of the Beauty who is “ever beyond” them, the Mystery of Infinite Splendor who sustains them all–who holds them in the palm of his hand–we try instead to grasp these finite things and make them the answer to our need for the Infinite.

This great tension at the heart of man’s religious sense– and the historical tragedy of man’s failure to live truly according the historical tragedy of man’s failure to live truly according to the religious sense–generates within the heart of man the longing for salvation. Corresponding to this longing, Giussani says, is the recognition of the possibility of revelation. Might not the Infinite Mystery make Himself manifest in history, create a way within history for me to reach Him? Might not the Infinite Mystery who constitutes my happiness approach me, condescend to my weakness, guide my steps toward Him? This possibility–the possibility of Divine Revelation–is profoundly “congenial” to the human person, because man feels profoundly his need for “help” in achieving his mysterious destiny.

The Religious Sense concludes on this note: the possibility of revelation. Here the ground is laid for the second book in what might be called Giussani’s catechesis of Christian anthropology: The Origin of the Christian Claim. In this book, Giussani will propose that Christ is the revelation of God in history, the Mystery drawn close to man’s life–walking alongside the human person. Christ is the great Divine help to the human person on the path to true happiness.

This an excerpt of the essay, Man in the Presence of Mystery. The author, John Janaro, professor of theology at Christendom College, delivered this paper in 1998.

What is Luigi Giussani’s Contribution To Catholic Theology?

The preceding account [see who is Luigi Giussani] might lead one to believe that the

significance of Luigi Giussani is primarily that of a teacher and spiritual leader. It would be an unfortunate mistake, however, to view him in this way if it led one to dismiss Giussani’s vast literary output, and its contribution to the intellectual life of the Church and our times. In this essay, we want to give a brief outline of the central thesis of the book by Giussani that has recently been published in a scholarly edition in English, entitled The Religious Sense. Here, we hope, it will become clear that Giussani’s thought presents a profound theological analysis of human “psychology” (in the classical sense of this term); indeed, it represents a tremendous resource toward the development of a fully adequate Catholic theological anthropology.

significance of Luigi Giussani is primarily that of a teacher and spiritual leader. It would be an unfortunate mistake, however, to view him in this way if it led one to dismiss Giussani’s vast literary output, and its contribution to the intellectual life of the Church and our times. In this essay, we want to give a brief outline of the central thesis of the book by Giussani that has recently been published in a scholarly edition in English, entitled The Religious Sense. Here, we hope, it will become clear that Giussani’s thought presents a profound theological analysis of human “psychology” (in the classical sense of this term); indeed, it represents a tremendous resource toward the development of a fully adequate Catholic theological anthropology.

Giussani proposes what he calls “the religious sense” as the foundation of the human person’s awareness of himself and his concrete engagement of life. The term “religious sense” does not imply that Giussani thinks that man’s need for religion is part of the organic structure of his bodily senses, nor does he mean that religion is to be defined as a mere emotional sensibility or a vague kind of feeling. Rather, Giussani uses the term “sense” here in the same way that we refer to “common sense” or the way that John Henry Newman sought to identify what he called the “illative sense.” “Sense” refers to a dynamic spiritual process within man; an approach to reality in which man’s intelligence is fully engaged, but not according to those categories of formal analysis that we call “scientific.” Giussani’s understanding of the “religious sense” in man has a certain kinship to Jacques Maritain’s view that man can come to a “pre-philosophical” or “pre-scientific” awareness of the existence of God, in that both positions insist that reason is profoundly involved in the approach to God for every human being–not just for philosophers. What is distinctive about Giussani’s approach, however, is his effort to present a descriptive analysis of the very core of reason, the wellspring from which the human person, through action, enters into relationship with reality. Needless to say, “action” in the Giussanian sense is not simply to be identified with an external “activism,” but involves also and primarily what Maritain would call the supremely vital act by which man seeks to behold and embrace truth, goodness, and beauty–those interrelated transcendental perfections inherent in all things which Giussani refers to by a disarmingly simple term: meaning.

Giussani proposes that we observe ourselves “in action,” and investigate seriously the fundamental dispositions and expectations that shape the way we approach every circumstance in life. In so doing, we will discover that the “motor” that generates our activity and places us in front of things with a real interest in them is something within ourselves that is both reasonable and mysterious. It is something so clear and obvious that a child can name it, and yet it is something so mysterious that no one can really define what it is: it is the search for happiness. The human heart–in the biblical sense, as the center of the person, the foundation of intelligence and freedom, and not merely the seat of infrarational emotions and sentiments–seeks happiness in all of its actions. Here, of course, Giussani is saying the same thing as St. Thomas Aquinas. Giussani opens up new vistas on this classical position, however, by engaging in an existentially attentive analysis of the characteristics of this “search.” Giussani emphasizes the dramatic, arduous, and mysterious character of the need for happiness as man actually experiences it. He says that if we really analyze our desires and expectations, even in the most ordinary and mundane circumstances, what we will find is not some kind of desire for happiness that we can easily obtain, package, and possess through our activity. Rather we will see that genuine human action aims at “happiness” by being the enacted expression of certain fundamental, mysterious, and seemingly open-ended questions. The heart, the self, when acting–when the person is working, playing, eating, drinking, rising in the morning, or dying–is full of the desire for something and the search for something that it does not possess, that it cannot give to itself, and that it does not even fully understand, although the heart is aware that this Object is there, and its attainment is a real possibility.

Giussani proposes that we observe ourselves “in action,” and investigate seriously the fundamental dispositions and expectations that shape the way we approach every circumstance in life. In so doing, we will discover that the “motor” that generates our activity and places us in front of things with a real interest in them is something within ourselves that is both reasonable and mysterious. It is something so clear and obvious that a child can name it, and yet it is something so mysterious that no one can really define what it is: it is the search for happiness. The human heart–in the biblical sense, as the center of the person, the foundation of intelligence and freedom, and not merely the seat of infrarational emotions and sentiments–seeks happiness in all of its actions. Here, of course, Giussani is saying the same thing as St. Thomas Aquinas. Giussani opens up new vistas on this classical position, however, by engaging in an existentially attentive analysis of the characteristics of this “search.” Giussani emphasizes the dramatic, arduous, and mysterious character of the need for happiness as man actually experiences it. He says that if we really analyze our desires and expectations, even in the most ordinary and mundane circumstances, what we will find is not some kind of desire for happiness that we can easily obtain, package, and possess through our activity. Rather we will see that genuine human action aims at “happiness” by being the enacted expression of certain fundamental, mysterious, and seemingly open-ended questions. The heart, the self, when acting–when the person is working, playing, eating, drinking, rising in the morning, or dying–is full of the desire for something and the search for something that it does not possess, that it cannot give to itself, and that it does not even fully understand, although the heart is aware that this Object is there, and its attainment is a real possibility.

Giussani claims that religiosity coincides with these fundamental questions:

Giussani claims that religiosity coincides with these fundamental questions:

The religious factor represents the nature of our “I” in as much as it expresses itself in certain questions: “What is the ultimate meaning of existence?” or “Why is there pain and death, and why, in the end, is life worth living?” Or, from another point of view: “What does reality consist of and what is it made for?” Thus, the religious sense lies within the reality of our self at the level of these questions.

This means that, according to Giussani, man becomes authentically religious to the extent that he develops and articulates in the face of the circumstances of life the basic natural complex of questions or “needs” that are identified in the first chapter of the book as constitutive of the human heart: the need for truth, justice, goodness, happiness, beauty.

This complex of “needs” which constitutes the human heart by nature, will become more and more explicit and urgent as the person lives life and pursues the things that attract him, if he is truly honest with himself.

This an excerpt of the essay, Man in the Presence of Mystery. The author, John Janaro, professor of theology at Christendom College, delivered this paper in 1998.