Category: Culture

Krakow prayer meeting in 2009 sponsored by Sant’Egidio

On November 21, Andrea Riccardi, the founder of the international Community of Sant’Egidio announced that the next international inter-religious encounter, in 2009, will be in Krakow, Poland, honoring the memory of the Servant of God Pope John Paul II and to recall the terrible tragedy of Auschwitz, where evil manifested its ugly face.

On November 21, Andrea Riccardi, the founder of the international Community of Sant’Egidio announced that the next international inter-religious encounter, in 2009, will be in Krakow, Poland, honoring the memory of the Servant of God Pope John Paul II and to recall the terrible tragedy of Auschwitz, where evil manifested its ugly face.

World leaders, religious and political, have met for prayer periodically since 1986 when the landmark event was first lived in Assisi.

The H2O News video report.

The Community of Sant’Egidio has been in the United States since 1990, more info is found here.

The Wiki article is here.

“Christ without Culture” is untenable for Christians

First Things editor-in-chief Father Richard John Neuhaus puts his finger on a persistent topic that concerns me at this time: Christ and culture. In “The Deadly Convenience of Christianity Without Culture” Neuhaus briefly explores what it means to be an engaged member of the Church, the Body of Christ. He identifies what the Church is and how she is to act.

What I am seeing, and you may be seeing a similar thing, is that Church (clergy and laity alike) are giving into the pressure from the radical secularists to remove the Christian proposal from the public platform. A good example is the South Carolina politician who wanted to refuse a local Catholic Church from expanding because the Catholics were against abortion, women priests and held “ideologies” (i.e., theology) that conflicted with Unitarian Universalist “freedoms.” Of course, it is not only the outside world that is becoming more and more reticent toward the Church, it’s those who make the claim of being Catholic who are speaking less of Christ, the Church and true Christian living that makes me unnerved and thus becoming biege, even engaging in spiritual malpractice.

Christians seem to be accepting that belief in Christ and the flourishing of faith in world is irrelevant. Can it be that Christians are willing to absent themselves more and more from a public discussion of what it means to live morally, or the exploration of how faith and reason intersect, or the reality of life issues which holds to a principle of human dignity, or the need for a sensible national security plan, or the requirement of just immigration policies, or an adequate distribution of natural resources which feeds the hungry, clothes the naked and give drink to the thirsty? Do we not see the face of God in the world around us? How can it be that some of us call ourselves Christians and yet shy away from actually living the Gospel? How is it that professed Christians, clergy and laity alike, are ashamed at being identified as Christian in the public square? Are these questions above your pay grade? Is virtue that shameful that it can’t be spoken of or demonstrated? Is faith in Christ truly a mere private affair that one’s engagement in culture (art, politics, economics, romance, religion, friendship, etc.) can actually thrive without Christ?

I am hopeful that Catholics will begin to see that the notion of “Christ without cultural” is an impossible way to live, that is, bankrupt, and therefore pick up the shovel and starting digging a new foundation for the Gospel of Jesus Christ to be built upon. We are baptized into a communion, a Church, not a social club. We need to do more than just show up for “church.” Either is Christ King of heaven and earth, or we’re in trouble. How will our lives different this week?

Looking deeply into reality through the perspective of Georges Rouault

Do you know the work of Georges Rouault? Well you should. Franco Mormando writes

“Of Clowns And Christian Conscience: The art of Georges Rouault”

in the November 24th issue of America Magazine. The article follows.

Georges Rouault was 34 years old and barely recovered from a physical and nervous breakdown when he had a life-changing epiphany in 1905, which he described in a letter to his friend, édouard Schuré. While out walking one day, the artist happened to come across a “nomad caravan, parked by the roadside.” It was a circus, preparing for its next public performance. Rouault’s eye fell upon one of the figures: an “old clown sitting in a corner of his caravan in the process of mending his sparkling and gaudy costume.” It was then that Rouault had a piercing flash of insight, one that was to affect deeply his vision of life and art.

The artist was utterly struck by the jarring contrast between the clown’s external garb and

professional accoutrements–“brilliant scintillating objects, made to amuse”–and the wretchedness of his condition as an impoverished, vagabond laborer living on the fringes of society, enduring a “life of infinite sadness, if seen from slightly above.” From that contrast came another equally eye-opening realization: “I saw quite clearly that the ‘Clown’ was me, was us, nearly all of us…. This rich and glittering costume, it is given to us by life itself, we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume….” (Rouault summed up this vision in several studies entitled “Sunt Lacrymae Rerum”–“There are tears [of grief] at the very heart of things.”)

professional accoutrements–“brilliant scintillating objects, made to amuse”–and the wretchedness of his condition as an impoverished, vagabond laborer living on the fringes of society, enduring a “life of infinite sadness, if seen from slightly above.” From that contrast came another equally eye-opening realization: “I saw quite clearly that the ‘Clown’ was me, was us, nearly all of us…. This rich and glittering costume, it is given to us by life itself, we are all more or less clowns, we all wear a glittering costume….” (Rouault summed up this vision in several studies entitled “Sunt Lacrymae Rerum”–“There are tears [of grief] at the very heart of things.”)

From that moment on, the clown, as well as other circus figures and denizens of the disreputable periphery of society, haunted Rouault’s imagination and art, becoming one of his signature icons. An icon of what? Of the painful disconnection between appearances and reality, between who we are on the inside and who we pretend to be, or what society judges us to be, on the outside. Rouault confronts us on the one hand with clowns and prostitutes, whose real (if battered and buried) human dignity nonetheless still emits some light from within their souls, and on the other hand with the furthest extreme of the social spectrum: the rich, the well-born, the powerful, the “glitterati,” wearing the masks of their expensive clothes and polished manners, hiding cruel, narcissistic hearts full of dust and ashes. (See, for example, Rouault’s “The Accused” of 1907 and “Superman” of 1916). In his professional life Rouault knew this type well, for it was and is a familiar figure in the upper echelons of the art establishment. His own art dealer, the unsavory but hugely successful Ambroise Vollard, certainly seems to have been of that ilk.

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of Rouault’s death, the McMullen Museum at Boston College has mounted a magnificent, comprehensive review of his prodigiously productive career, Mystic Masque: Semblance and Reality in Georges Rouault, 1871-1958, on view until Dec. 7. This landmark exhibition features over 180 works from every period of the artist’s life, some never before seen in the United States. The exhibition was boldly conceived and curated by Stephen Schloesser, S.J., of the Boston College History Department, who also edited an ample and illuminating catalog that features interdisciplinary contributions from more than 20 scholars.

The key word is “masque,” meaning both “theatrical face cover” and “masked pageant” (think of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death”). Not only in his clown paintings, but everywhere in his art, Rouault explores–and provokes his viewers into exploring–the private human reality behind the public mask in order to expose the soul. In that exposure, the high and mighty are reduced to the level of the risible, if not the pathetic (as in his 1927 aquatint, “As proud of her noble stature as if she were still alive”), while the lowly are made to shine in their inherent human dignity. Again, as the artist himself explained to Schuré: “I have the defect…of leaving no one his glittering costume, be he king or emperor. I want to see the soul of the man in front of me…and the greater he is, the more mankind glorifies him, the more I fear for his soul.” In Schloesser’s view, “Rouault felt compelled to unmask society’s well-respected and well-born, and to raise up society’s lowly and overlooked.” In other words, Rouault’s art comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable. It is an art that a Peter Maurin or a Dorothy Day would assuredly have cherished.

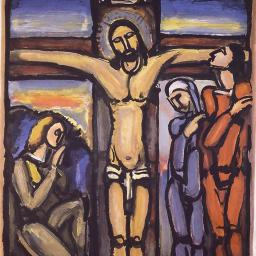

With his fertile imagination and years of productivity, Rouault treated many different themes beyond clowns and masks and employed a variety of media and styles. A revelation for me, and, I suspect, for many viewers, is the Rembrandt-inspired style of his earliest period, represented in the exhibition by two stirring canvases, “The Way to Calvary” and “Job.” But perhaps his most enduring stylistic trademark is the use of richly luminous colors gleaming forth from a heavy matrix of thick black lines, clearly the influence of his youthful apprenticeship with stained-glass makers. The exhibition includes one actual stained-glass window by Rouault, a crucifixion scene, and it is simply a gem in the literal sense of that word.

With his fertile imagination and years of productivity, Rouault treated many different themes beyond clowns and masks and employed a variety of media and styles. A revelation for me, and, I suspect, for many viewers, is the Rembrandt-inspired style of his earliest period, represented in the exhibition by two stirring canvases, “The Way to Calvary” and “Job.” But perhaps his most enduring stylistic trademark is the use of richly luminous colors gleaming forth from a heavy matrix of thick black lines, clearly the influence of his youthful apprenticeship with stained-glass makers. The exhibition includes one actual stained-glass window by Rouault, a crucifixion scene, and it is simply a gem in the literal sense of that word.

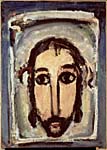

Rouault uses the same stained-glass-inspired style to perhaps its most memorable effect in

his many depictions of the “Holy Face,” the face of the suffering Jesus as traditionally seen in representations of the sudarium of St. Veronica, which, according to pious belief, shows the true likeness of Christ. The face of Christ is an almost obsessive visual leitmotif for Rouault, a potent symbol of the suffering of an innocent humanity oppressed by an unjust society.

his many depictions of the “Holy Face,” the face of the suffering Jesus as traditionally seen in representations of the sudarium of St. Veronica, which, according to pious belief, shows the true likeness of Christ. The face of Christ is an almost obsessive visual leitmotif for Rouault, a potent symbol of the suffering of an innocent humanity oppressed by an unjust society.

Another disturbing existential question is raised by Rouault’s art, most literally in the title he gives to several of his works: “Are we not all slaves?” Here Rouault is speaking from bitter personal experience. In 1917, desperately poor and with a family to support, he was forced into what was essentially indentured servitude to that same infamous art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, or Fifi Voleur (Fifi the Thief) as Gauguin called him, a cunning businessman whose ambiguous personal life had much to hide, as Christopher Benfey has probingly written for the online magazine Slate.

Those who prefer art that presents only what Charles Baudelaire would call “la vie en beau” (the pretty side of life) or who shun the examination of conscience might not fully savor this exhibition, but Rouault’s style is so visually compelling that it will certainly arrest anyone’s attention and ultimately give delight on some level. For many viewers, I dare say, questions surrounding the moral life, social justice, sincerity and authenticity will likely dominate their response to this exhibition, as they dominated Rouault’s artistic imagination and as they dominate the conception of the exhibition itself.

Rouault is probably familiar to anyone who went through the parochial school system in the United States. My own introduction to “Rouault the Catholic artist” occurred many years ago at Cardinal Hayes High School in the Bronx. Yet Rouault himself (a true believer, albeit not of the orthodox kind) rejected the very notion of sacred art or the “Catholic artist.” “There is no sacred art,” he has been quoted as having said. “There is just art pure and simple.” Nonetheless, Rouault’s work not only has the power to please the eye and feed the mind, but to quicken our attention to the moral and spiritual dimension of human experience and to help move us to a higher plane of consciousness.

Explaining the Clash in the Holy Sepulchre

Edward Pentin writing for Terrasanta.net tries to contextualize the rather distasteful events among “Christians” at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre earlier in the month. I am still trying to wrap my mind around the complexities that exist in the Holy Land. Certainly, there are many and not easy to sort out. But the scandal of these “ecclesial acts” by betray the fragility of faith and lack of engagement in the spiritual life. For the life me I can’t help but think these monks have abandoned faith and salvation in Christ and yet persist in living as monks, at least on the superficial level.

International Meeting of Prayer for Peace sponsored by the Community of Sant’Egidio

The Civilization of Peace: Faiths and Cultures in Dialogue

The meeting, which has been promoted by the Community of Sant’Egidio and the Church of Cyprus, takes place in Nicosia from 16 to 18 November.

The meeting, which has been promoted by the Community of Sant’Egidio and the Church of Cyprus, takes place in Nicosia from 16 to 18 November.

The Cyprus date is a further leg of the pilgrimage undertaken by the Community of Sant’Egidio to carry forward the legacy of the historic World Day of Prayer for Peace convened in Assisi by Pope John Paul II on October 27, 1986.

Over these twenty-two years, invitations from the Community have led men and women from diverse cultures and religions onto the pathway of encounter, dialogue and prayer for peace. The pilgrimage has called on various locations around the world, spreading the “Spirit of Assisi”, creating ties of friendship and cooperation, testifying to a common will to create a culture of coexistence.

On opening the last meeting, held in Naples in October 2007, Pope Benedict 16th stated: “In respecting the differences between the various faiths, we are all called upon to work for peace and to make a concrete effort to further reconciliation between nations. This is the authentic “Spirit of Assisi”… religions can and must offer a precious resource for constructing a peaceful humanity, because they speak of peace being at the heart of humankind”.

The Cyprus Meeting constitutes part of this commitment.

The island, lying at the heart of the Mediterranean, touched on by the preaching of St Paul the Apostle, place of encounter between a variety of cultures and religions, will host several hundred figures from every part of the world: representatives of the worlds of religion, of culture and of politics. They will enliven around 20 “round tables”, open – as is the tradition at these encounters – to participation by the public.

The Closing Ceremony will take place on November 18 in the heart of the capital, Nicosia; it will feature the proclamation the Appeal for Peace.

As in previous years, this site will follow the event via a live video web-link.

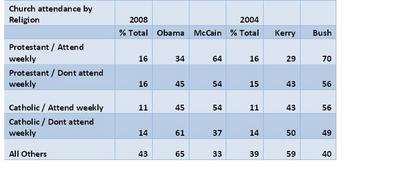

Making sense of the election according to religious observance

2 Jesuit Priests Killed in Moscow

From the News Services…

Moscow – Two Jesuit priests died of knife wounds in Moscow, Russian news agencies said

Wednesday. Father Igor Kovalevsky, the general secretary of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said the priests bodies were found in their central Moscow apartment late Tuesday.

Wednesday. Father Igor Kovalevsky, the general secretary of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference, said the priests bodies were found in their central Moscow apartment late Tuesday.

Kovalevsky called the incident a “brutal murder.”

Police at the scene said the two men had died of blows to the head and knife wounds. Authorities said the motive for the killing was unknown.

News agency Ria-Novosti named the victims as Russian national Otto Messmer, 46, and South American priest Victor Betancourt, 42.

From the General Curia of the Society of Jesus…

On Saturday 25 October, Father Victor Betancourt, an Ecuadorian Jesuit working in the St. Thomas Philosophical, Theological and Historical Institute in

The police investigations have yet to come to any firm conclusions about cause of these violent deaths.

Father Otto Messmer, son of a profoundly Catholic family of German origin and a Russian citizen, was born on

Father Victor Betancourt was born on

May their memory be eternal!

Catholic Underground NYC: November 1

…will be meeting this coming Saturday, All Saints Day, November 1st

Adoration of the Most Blessed Sacrament and Vespers followed by music by

Keith Moore

The evening will start at

Our Lady of Good Council Church

The Catholic Underground happens every 1st Saturday of the month, from