The liturgical memorial of Saint Philip Neri fell on Sunday but it was transferred to this day in Oratorian communities. One cannot pass on prayerfully remembering this Apostle to Rome. Neri is one of the most esteemed saints of the 16th century coupled with people like Loyola. Fr George Rutler, priest of the Archdiocese of New York offers a meditation on Saint Philip, drawing some very important points about person and ministry of the Saint.

The liturgical memorial of Saint Philip Neri fell on Sunday but it was transferred to this day in Oratorian communities. One cannot pass on prayerfully remembering this Apostle to Rome. Neri is one of the most esteemed saints of the 16th century coupled with people like Loyola. Fr George Rutler, priest of the Archdiocese of New York offers a meditation on Saint Philip, drawing some very important points about person and ministry of the Saint.

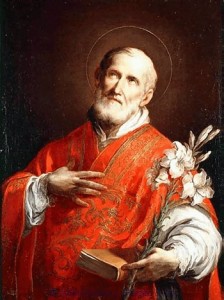

The feast of St. Philip Neri (1515 – 1595) falls this Monday, on the same day that the civil calendar memorializes those who gave their lives in the service of our country. Philip was a soldier, too, albeit a soldier of Christ, wearing “the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God” (Ephesians 6:17). He lived in a decadent time when many who called themselves Christians chose to be pacifists in the spiritual combat against the world, the flesh and the Devil.

In the battle for souls, Philip’s most effective weapons were gentleness and mercy, though he was also a master of “tough love” when it was necessary to correct those inclined to be spiritual deserters. Although he was reared in Florence, Philip’s pastoral triumphs gained him the title “Apostle of Rome.” It was said of the Emperor Augustus that he found Rome brick and left it marble, and in a moral sense the same might be said of Philip. The Sacred City was not so sacred in the minds of many, and his chief weapon for reforming it was penance.

After eighteen years in Rome, Philip was ordained at the age of thirty-five. He polished rough souls every day in the confessional, where he might be found at all hours of the day and night for forty-five years. In the words of Blessed John Henry Newman, who joined the saint’s Oratory three centuries later, “He was the teacher and director of artisans, mechanics, cashiers in banks, merchants, workers in gold, artists, men of science. He was consulted by monks, canons, lawyers, physicians, courtiers; ladies of the highest rank, convicts going to execution, engaged in their turn his solicitude and prayers.” We have an audible relic of him in the oratorio, the musical form he invented as a means of catechesis. His magnetic appeal to the most stubborn and cynical types of people seems hardly less miraculous than the way he sometimes levitated during Mass, requiring that he offer the Holy Sacrifice privately because, as the Pope prudently if understatedly said, the spectacle might distract the faithful.

Refusing high clerical rank, and disdaining any sort of human honor, Philip’s power intimidated the Prince of Lies as much as any earthly prince. There is a lesson in this for our own urban culture, and certainly for us providentially located in “Hell’s Kitchen.” The temptation is for the Church to give up on spiritual combat and retreat to the suburbs. This is a false strategy since no terrain, concrete or bucolic, offers a complete escape from the Church’s field of combat. While consolidation of strength is a necessary strategy, there is no substitute for victory. If General MacArthur maintained that principle with earthly effect, so much more do the saints struggle, knowing that Christ has already won the victory, but also aware that to flee the field is to lose him forever