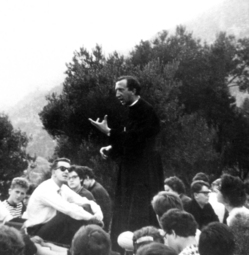

The preceding account [see who is Luigi Giussani] might lead one to believe that the

significance of Luigi Giussani is primarily that of a teacher and spiritual leader. It would be an unfortunate mistake, however, to view him in this way if it led one to dismiss Giussani’s vast literary output, and its contribution to the intellectual life of the Church and our times. In this essay, we want to give a brief outline of the central thesis of the book by Giussani that has recently been published in a scholarly edition in English, entitled The Religious Sense. Here, we hope, it will become clear that Giussani’s thought presents a profound theological analysis of human “psychology” (in the classical sense of this term); indeed, it represents a tremendous resource toward the development of a fully adequate Catholic theological anthropology.

significance of Luigi Giussani is primarily that of a teacher and spiritual leader. It would be an unfortunate mistake, however, to view him in this way if it led one to dismiss Giussani’s vast literary output, and its contribution to the intellectual life of the Church and our times. In this essay, we want to give a brief outline of the central thesis of the book by Giussani that has recently been published in a scholarly edition in English, entitled The Religious Sense. Here, we hope, it will become clear that Giussani’s thought presents a profound theological analysis of human “psychology” (in the classical sense of this term); indeed, it represents a tremendous resource toward the development of a fully adequate Catholic theological anthropology.

Giussani proposes what he calls “the religious sense” as the foundation of the human person’s awareness of himself and his concrete engagement of life. The term “religious sense” does not imply that Giussani thinks that man’s need for religion is part of the organic structure of his bodily senses, nor does he mean that religion is to be defined as a mere emotional sensibility or a vague kind of feeling. Rather, Giussani uses the term “sense” here in the same way that we refer to “common sense” or the way that John Henry Newman sought to identify what he called the “illative sense.” “Sense” refers to a dynamic spiritual process within man; an approach to reality in which man’s intelligence is fully engaged, but not according to those categories of formal analysis that we call “scientific.” Giussani’s understanding of the “religious sense” in man has a certain kinship to Jacques Maritain’s view that man can come to a “pre-philosophical” or “pre-scientific” awareness of the existence of God, in that both positions insist that reason is profoundly involved in the approach to God for every human being–not just for philosophers. What is distinctive about Giussani’s approach, however, is his effort to present a descriptive analysis of the very core of reason, the wellspring from which the human person, through action, enters into relationship with reality. Needless to say, “action” in the Giussanian sense is not simply to be identified with an external “activism,” but involves also and primarily what Maritain would call the supremely vital act by which man seeks to behold and embrace truth, goodness, and beauty–those interrelated transcendental perfections inherent in all things which Giussani refers to by a disarmingly simple term: meaning.

Giussani proposes that we observe ourselves “in action,” and investigate seriously the fundamental dispositions and expectations that shape the way we approach every circumstance in life. In so doing, we will discover that the “motor” that generates our activity and places us in front of things with a real interest in them is something within ourselves that is both reasonable and mysterious. It is something so clear and obvious that a child can name it, and yet it is something so mysterious that no one can really define what it is: it is the search for happiness. The human heart–in the biblical sense, as the center of the person, the foundation of intelligence and freedom, and not merely the seat of infrarational emotions and sentiments–seeks happiness in all of its actions. Here, of course, Giussani is saying the same thing as St. Thomas Aquinas. Giussani opens up new vistas on this classical position, however, by engaging in an existentially attentive analysis of the characteristics of this “search.” Giussani emphasizes the dramatic, arduous, and mysterious character of the need for happiness as man actually experiences it. He says that if we really analyze our desires and expectations, even in the most ordinary and mundane circumstances, what we will find is not some kind of desire for happiness that we can easily obtain, package, and possess through our activity. Rather we will see that genuine human action aims at “happiness” by being the enacted expression of certain fundamental, mysterious, and seemingly open-ended questions. The heart, the self, when acting–when the person is working, playing, eating, drinking, rising in the morning, or dying–is full of the desire for something and the search for something that it does not possess, that it cannot give to itself, and that it does not even fully understand, although the heart is aware that this Object is there, and its attainment is a real possibility.

Giussani proposes that we observe ourselves “in action,” and investigate seriously the fundamental dispositions and expectations that shape the way we approach every circumstance in life. In so doing, we will discover that the “motor” that generates our activity and places us in front of things with a real interest in them is something within ourselves that is both reasonable and mysterious. It is something so clear and obvious that a child can name it, and yet it is something so mysterious that no one can really define what it is: it is the search for happiness. The human heart–in the biblical sense, as the center of the person, the foundation of intelligence and freedom, and not merely the seat of infrarational emotions and sentiments–seeks happiness in all of its actions. Here, of course, Giussani is saying the same thing as St. Thomas Aquinas. Giussani opens up new vistas on this classical position, however, by engaging in an existentially attentive analysis of the characteristics of this “search.” Giussani emphasizes the dramatic, arduous, and mysterious character of the need for happiness as man actually experiences it. He says that if we really analyze our desires and expectations, even in the most ordinary and mundane circumstances, what we will find is not some kind of desire for happiness that we can easily obtain, package, and possess through our activity. Rather we will see that genuine human action aims at “happiness” by being the enacted expression of certain fundamental, mysterious, and seemingly open-ended questions. The heart, the self, when acting–when the person is working, playing, eating, drinking, rising in the morning, or dying–is full of the desire for something and the search for something that it does not possess, that it cannot give to itself, and that it does not even fully understand, although the heart is aware that this Object is there, and its attainment is a real possibility.

Giussani claims that religiosity coincides with these fundamental questions:

Giussani claims that religiosity coincides with these fundamental questions:

The religious factor represents the nature of our “I” in as much as it expresses itself in certain questions: “What is the ultimate meaning of existence?” or “Why is there pain and death, and why, in the end, is life worth living?” Or, from another point of view: “What does reality consist of and what is it made for?” Thus, the religious sense lies within the reality of our self at the level of these questions.

This means that, according to Giussani, man becomes authentically religious to the extent that he develops and articulates in the face of the circumstances of life the basic natural complex of questions or “needs” that are identified in the first chapter of the book as constitutive of the human heart: the need for truth, justice, goodness, happiness, beauty.

This complex of “needs” which constitutes the human heart by nature, will become more and more explicit and urgent as the person lives life and pursues the things that attract him, if he is truly honest with himself.

This an excerpt of the essay, Man in the Presence of Mystery. The author, John Janaro, professor of theology at Christendom College, delivered this paper in 1998.