Moving through the summer, we arrive today at the 15th Sunday through the Church Year when we hear from Saint Luke (10:25-37): the parable of the Good Samaritan — love your neighbor. This not a nice story. You are familiar with the narrative not only because it is memorable but because it is challenging and a most difficult thing in being a true follower of Jesus Christ. Most clearly, the work of conversion to holiness, our companionship with Christ and our life in the Church includes the content of this gospel pericope. You might think of linking this parable with Matthew 25 where it speaks about the Kingdom and the works of mercy.

Moving through the summer, we arrive today at the 15th Sunday through the Church Year when we hear from Saint Luke (10:25-37): the parable of the Good Samaritan — love your neighbor. This not a nice story. You are familiar with the narrative not only because it is memorable but because it is challenging and a most difficult thing in being a true follower of Jesus Christ. Most clearly, the work of conversion to holiness, our companionship with Christ and our life in the Church includes the content of this gospel pericope. You might think of linking this parable with Matthew 25 where it speaks about the Kingdom and the works of mercy.

It is clear from the Lord’s perspective we need to love all people (the neighbor), even loving our enemy. No one gets to pick and choose who to love and who not to love. The power of the holy gospel is that it is not tribal but universal. The power of the gospel knows no need other need than to know, love and serve God and our neighbor as ourself. The Gospel does not admit socio-economic, racial or gender theories into its message. Least of all the gospel is not a mere trend. We know something radically different here. Love is not a sentiment, it is a verb with much content; it generates a new human person made in God’s image and likeness. Love is showing concern for the other person’s eternal destiny. It is about wholeness and beauty, about relationality and perfection (as God would have it).

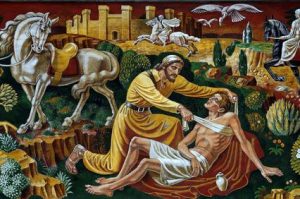

The question arises: who is my neighbor? It is the person nearest, or neediest? Is it both? What does it mean to be a neighbor in the 21st century? How do we judge? What is the criteria? We have to answer as the man asked by Jesus, who most proved to be the neighbor’ to the man in need? How am I ‘neighbor’ to others? This gospel given to us by the Church for today is very connected to the violence we are experiencing now in the USA. Our neighbor is not a definition. A way to get to the heart of knowing the meaning of what it means to be a neighbor: while we are called to be good as the samaritan was. Can the despised, hated person be the person we need to be a part of our life so as to know and love the Kingdom of God on earth, and in heaven? In this way a new humanity is generated by the act of mercy; a new creation is made known to the world. Remember, Samaritans and Jews are enemies in the time of Jesus. Jerusalem is symbolic of heaven, the way we ought to be by God’s grace; Jerecho is symbolic of sin, a city of dysfunction. As the narrative goes, a man gets robbed and beaten going from Jerusalem to Jericho and he cannot help himself and needs someone. The priest and Levite represent the officials of religion and are twisted in the spiritual life and refuse to help the man in need. The Samaritan, the outsider, whose gaze is compassionate. Think of the samaritan and how he, the hated person of Israel, helps the person who hates him. The Samaritan for us is Jesus Christ –the outsider, the hated man, the one who is a slave (as St Paul would say) — He pours into our souls oil and wine (the sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation, Ordination and the Eucharist). July is the month of the Precious Blood and here we believe that Christ pours into us His life-giving blood. Thus, making Jesus the Savior –the one who heals. Just as the Good Samaritan brings the man to an inn and pays the price for the service; we read and hear this narrative and know that Jesus Christ brings us to the community of faith, the Church and pays the price for our healing, to save us.

Would Jesus be partial in His concern, his love if He loved only those who agreed with Him, and did what He said to do? Recall Jesus’ interchange on with the people around Him as He hung on the Cross. Jesus asks in today’s parable who cared most for the victim. The answer came: the one who treated the man with mercy. The response Jesus gave was, “Go and do likewise.” Is it possible for us to live in this manner?

Our meditation and our Christian work today is to ponder and to act upon this final sentence: go and do likewise. The teaching is clear: ‘real mercy (compassion) drives action’. This is a story of our fall and redemption. Yet, this gospel narrative is more than just identifying the neighbor, doing good, and being the best we can be –it is about how God the Father calls us into His presence by forgiving our sin and redeeming us through the sacrifice of His Only Begotten Son.

The patristic theologian Origen once said, “The saying: Be imitators of me as I am of Christ makes it clear that we can imitate Christ by showing mercy to those who have fallen into the hands of brigands. We can go to them, bandage their wounds after pouring in oil and wine, place them on our own mount, and bear their burdens.”

And if you need more help,

Saint Gregory Nazianzen taught: “You who are strong, help the weak. You who are rich, help the poor. You who stand upright, help the fallen and the crushed. You who are joyful, comfort those in sadness. You who enjoy all good fortune, help those who have met with disaster. Give something in thanksgiving to God that you are of those who can give help, and not of those who stand and wait for it.”

The human way of proceeding is usually one in which it is easier to show mercy for people we don’t see (hungry children of Africa, earthquake victims drug abusers); we can give money in the collection and not have to personally engage the other. Yet, some spurn the weak and hate their fellow man and woman. The challenge, therefore with the Christian, is to have mercy for those who we might not expect to have or to show mercy upon. In mercy, Jesus tells us that the Kingdom is made manifest. Ultimately, both those we do not see AND those we do see, need to have our mercy and the mercy of God (my sister, my alcoholic priest, my boss who knows only anger and resentment, the policeman, the person who does not obey traffic laws). Follow Jesus, and live the unexpected grace offered.