Silence in the monastery confuses the world; it sometimes confuses me and there are times that I am frustrated by silence. The practice of silence is often misunderstood by those who live in monasteries because of an insufficient understanding of a “theology of silence.” Family and friends think monks take a vow of silence. They get this idea from the clichés of the TV and movies where they see monks and nuns piously walking the halls of the abbey in silence with a mean looking superior hovering over the shoulder waiting for someone to slip-up. While I don’t deny that this understanding may be rooted in some truth, or a least a vague sense of truth, it nonetheless lends itself to gross misunderstanding of the role of silence in the monastic life, indeed the need (and desire for) for silence in all people’s lives.

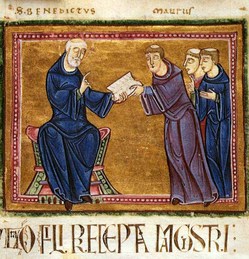

What did Saint Benedict say about the practice of silence in his Rule? In one place he says:

Let us do what the Prophet says: “I said, I will take heed of my ways, that I sin not with my tongue: I have set a guard to my mouth, I was dumb, and was humbled, and kept silence even from good things” (Psalm 38[39]:2-3). Here the prophet shows that, if at times we ought to refrain from useful speech for the sake of silence, how much more ought we to abstain from evil words on account of the punishment due to sin.

Therefore, because of the importance of silence, let permission to speak be seldom given to perfect disciples even for good and holy and edifying discourse, for it is written: “In much talk up shall not escape sin” (Proverbs 10:19). And elsewhere: “Death and life are in the power of the tongue” (Proverbs 18:21). For it belongs to the master to speak and to teach; it becomes the disciple to be silent and to listen. If, therefore, anything must be asked of the Superior, let it be asked with all humility and respectful submission. But coarse jests, and idle words or speech provoking laughter, we condemn everywhere to eternal exclusion; and for such speech we do not permit the disciple to open his lips (Ch. 6).

Belmont Abbey’s Father Abbot, Placid, put in our mailboxes the community’s custom of silence that had been formulated in consultation with the community in 2006. Essentially it is outlines what’s permitted and what’s not. To me, it is less of a “wagging of the finger” as it is a way to focus our life yet again on a venerable practice that leads to freedom but yet takes discipline and freedom to engage our mind, hear and will. So what’s expected? Following Vespers (c. 7:30 pm) to the conclusion of breakfast (c. 8:00 am) silence is carefully observed throughout the monastery. Extended conversations may be had in designated areas like the common recreation areas, the formation study and the guest dining room. “A spirit of silence should be maintained in the hallways of the monastery at all times, and any conversation should be carried on in a quiet tone of voice.” Another place where we attempt to maintain silence is in the sacristy, the basilica and in the passage way between the abbey and the basilica. A stricter sense of being silent exists in the church prior to the Mass and the Divine Office, in the refectory before the evening meal which includes the brief reading of a chapter (a few lines really) of the Rule of Saint Benedict and during table reading (only 15 min.) and in “statio” (the order of seniority) prior to Sunday Mass and Vespers.

This work of silence is neither rigid and nor is unreasonable. In fact, I appreciate the periods of silence the community has worked out and I hope that my confreres will help me live by what’s expected.

When I am participating in community days of the Communion and Liberation (CL) movement I practice silence with the group. We don’t do this to shut up the incessant talker (though it’s a nice by-product of the silence) or to force an agenda as it is a method to help us (me) to appreciate the beauty of God the Father’s creation which is in front of us. So, it is not uncommon to walk in the woods, climbing a mountain, or sitting by the seashore and not talk to your neighbor. Sounds goofy? Perhaps for the uninitiated or the person who can’t grasp the need to soak in the beauty of life, indeed all of creation, without the distracting noise of talking all the time, silence would be difficult or unhelpful or somewhat silly.

Another example of the witness of silence is the Good Friday Way of the Cross that starts at Saint James Cathedral (Brooklyn) and ends at St. Peter’s Church (Barclay St., NYC–ground zero) but crosses the Brooklyn Bridge and makes other stops to pray, listen to Scripture and sing spiritual songs. Imagine 5000+ people making the Way of the Cross in silence in the chilly air! People in NYC walking in silence following a cross in silence! What’s the point? The point is: How does one understand, that is, judge (assess, evaluate, understand reality) the impact of the Lord’s saving life, death and resurrection if all you hear is chatter? The gospel is made alive by the witness of 5000+ people walking in silence.

One last example are my friends in the Fraternity of Saint Joseph (I call them CL’s contemplatives-in-the-world who follow the Fraternity of Communion and Liberation) who spend a portion of each day in silence and at least one other day in an extended period of silence. For me, this is a witness to the presence of Christ and one’s relationship with the Lord. Their discipline of silence is not merely turning off the radio, not speaking, not writing email or updating their blog, nor the simple absence of distracting noise but the intentional focus on the work of the Lord in prayer and study. How do you discern (verify) the will of God in the hussle-and-bussle of life? How do you hear the voice of the Lord calling you, as the Lord called Samuel or the apostles if all you encounter is the blaring of the stereo, the train or your mother yelling for you to answer the doorbell?

Theologically, I think Patriarch Bartholomew I (of Constantinople) said it well in an address a year ago:

The ascetic silence of apophaticism imposes on all of us — educational and ecclesiastical institutions alike — a sense of humility before the awesome mystery of God, before the sacred personhood of human beings, and before the beauty of creation. It reminds us that — above and beyond anything that we may strive to appreciate and articulate — the final word always belongs not to us but to God. This is more than simply a reflection of our limited and broken nature. It is, primarily, a calling to gratitude before Him who “so loved the world” (Jn 3:16) and who promised never to abandon us without the comfort of the Paraclete that alone “guides us to the fullness of truth.” (Jn 16:13) How can we ever be thankful enough for this generous divine gift?

So, in my context silence is not punitive or a burden but way of living with an awareness that would otherwise be minimized and likely forgotten.