Some people would trash even the good name of the dead to get media attention on their agenda. In this case, it seems as though the homosexual lobbyists are trying to make more of a good friendship than what really was there. That is, questions about Cardinal Newman’s sexuality, that he was same sex attracted, are surfacing with the goal of derailing the process of beatification/canonization. London’s Daily Mail published an article questioning the facts and the Catholic News Agency published this article. Father Kerr’s L’Osservatore Romano article follows; it was published today in the weekly English edition.

CARDINAL JOHN HENRY NEWMAN’S EXHUMATION OBJECTORS

Healthy manhood at the service of the Kingdom

Recently various newspapers have published articles on Venerable John Henry Newman, sowing doubts about his sexual inclination. The following is a clarification by Prof. Ian Ker, an eminent Newman scholar and Oxford University Professor.

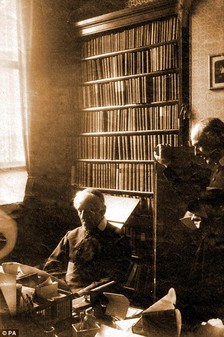

Professor Ian Ker

Oxford University, England

The exhumation of Venerable John Henry Newman’s body from his grave has led to calls in particular from the homosexual lobby that he should not be separated from his great friend and collaborator Fr Ambrose St John, in whose grave Newman is buried in accordance with his own specific wishes.

The implication of these protests is clear: that Newman wished to be buried with his

friend because, although no doubt chaste and celibate, nevertheless he had more than simply friendly feelings for St John.

friend because, although no doubt chaste and celibate, nevertheless he had more than simply friendly feelings for St John.

However, if wanting to be buried in the same grave as someone else indicates some kind of sexual love for the other person, then C.S. Lewis’ brother Warnie, who is buried in the same grave in accordance with both brothers’ wishes, must have had incestuous feelings for his brother.

Or again, G.K. Chesterton’s devoted secretary, Dorothy Collins, whom he and his wife regarded as a daughter, while thinking it presumptuous to ask to be buried in the same grave as the Chestertons, nevertheless directed that she be cremated and that her ashes should be buried in the same grave. Does this mean that she had more than filial feelings for one or both of her employers?

Ambrose St John was an extremely close friend of Newman. He had devoted himself for 30 years to the service of Newman, even asking if he might take a vow of obedience to him at his Confirmation, a request that was, of course, refused.

Newman blamed himself for his death, having asked him to translate the German theologian Joseph Fessler’s important book on infallibility in the wake of the First Vatican Council, a last labour of love that had proved too much for him, overworked as he already was.

In his dark last days as an Anglican, Newman said that Ambrose St John had come to him “as Ruth to Naomi”. After joining Newman’s semi-monastic community at Littlemore outside Oxford, he had remained as Newman’s closest supporter all through the difficulties of founding the Oratory of St Philip Neri in England and all through Newman’s many subsequent trials and tribulations as a Catholic.

In his Apologia pro Vita sua, Newman “with great reluctance” mentions that at the time of his first religious conversion when he was 15 he became convinced that “it would be the will of God that I should lead a single life”.

For the next 14 years, “with the break of a month now and then”, and then continuously, he believed that his “calling in life would require such a sacrifice”.

Needless to say, there were no “civil partnerships” between men then in what was still a Christian country where homosexual activity was punishable by imprisonment and was universally regarded as immoral. Newman, of course, is talking about marriage with a woman and the sacrifice that celibacy involved.

The only reason it could have been a sacrifice was because like any normal man Newman wished to get married. But, although not belonging to a church where celibacy was the rule or even the ideal, Newman, steeped in Scripture as he was, knew the words of our Lord: “there are eunuchs who have made themselves that way for the sake of the kingdom of heaven”.

Twenty five years after his youthful embrace of celibacy, we find Newman counting the cost, at the conclusion of the extraordinary account he wrote of his near fatal illness in Sicily in 1833: “The thought keeps pressing on me, while I write this, what am I writing it for?… Whom have I, whom can I have, who would take interest in it?… This is the sort of interest which a wife takes and none but she – it is a woman’s interest – and that interest, so be it, shall never be taken in me…. And therefore I willingly give up the possession of that sympathy, which I feel is not, cannot be, granted to me. Yet, not the less do I feel the need of it”.

In these moving sentences, written while he was still a clergyman of the Church of England and fully entitled to marry, we see Newman’s total commitment to the life of virginity to which he felt unmistakably called, but yet we can also feel the deep pain he experienced in sacrificing the love of a woman in marriage.

Finally, what should be said to those who think Newman’s wishes should be honoured and that Ambrose St John’s remains should be removed with his?

Throughout his life as a Catholic, Newman always insisted that whatever he wrote he wrote under the correction of Holy Mother Church. That was his constant refrain. If the Church decrees that his remains should be removed to a church, then Newman’s undoubted response would be that of his last testament, like everything else he wrote, he wrote under correction of higher authority.

And if that higher authority decrees that his body be removed and that of his friend left, then Newman would say without hesitation, “so be it”.