The key to living the spiritual life is the awareness we have of God’s (the Blessed Trinity’s) action in our lives. The daily reckoning of what, how, when, and perhaps why God acts in such way for, with and through us is essential for us because the journey of faith is not static but dynamic. Saint Ignatius of Loyola believed that we advance in the spiritual life by asking for the grace of insight into our lived experience and to interpret that experience light of the Incarnation. Father Hamm provides me (us) with a good primer on the Examen. His emphasis is on feelings but I think Hamm stands in good company especially when you read that Saint Augustine speak of zeroing-in on one’s feelings because God is right there.

About 20 years ago, at breakfast and during the few hours that followed, I had a small revelation. This happened while I was living in a small community of five Jesuits, all graduate students in New Haven, Connecticut. I was alone in the kitchen, with my cereal and the New York Times, when another Jesuit came in and said: “I had the weirdest dream just before I woke up. It was a liturgical dream. The lector had just read the first reading and proceeded to announce, ‘The responsorial refrain today is, If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.’ Whereupon the entire congregation soberly repeated, ‘If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.'” We both thought this enormously funny. At first, I wasn’t sure just why this was so humorous. After all, almost everyone would assent to the courageous truth of the maxim, “If at first…” It has to be a cross-cultural truism (“Keep on truckin’!”). Why, then, would these words sound so incongruous in a liturgy?*A little later in the day, I stumbled onto a clue. Another, similar phrase popped into my mind: “If today you hear his voice, harden not your hearts” (Psalm 95). It struck me that that sentence has exactly the same rhythm and the same syntax as: “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” Both begin with an if clause and end in an imperative. Both have seven beats. Maybe that was one of the unconscious sources of the humor.

The try-try-again statement sounds like the harden-not-your-hearts refrain, yet what a contrast! The latter is clearly biblical, a paraphrase of a verse from a psalm, one frequently used as a responsorial refrain at the Eucharist. The former, you know instinctively, is probably not in the Bible, not even in Proverbs. It is true enough, as far as it goes, but it does not go far enough. There is nothing of faith in it, no sense of God. The sentiment of the line from Psalm 95, however, expresses a conviction central to Hebrew and Christian faith, that we live a life in dialogue with God. The contrast between those two seven-beat lines has, ever since, been for me a paradigm illustrating that truth.

Yet how do we hear the voice of God? Our Christian tradition has at least four answers to that question. First, along with the faithful of most religions, we perceive the divine in what God has made, creation itself (that insight sits at the heart of Christian moral thinking). Second, we hear God’s voice in the Scriptures, which we even call “the word of God.” Third, we hear God in the authoritative teaching of the church, the living tradition of our believing community. Finally, we hear God by attending to our experience, and interpreting it in the light of all those other ways of hearing the divine voice-the structures of creation, the Bible, the living tradition of the community.

The phrase, “If today you hear his voice,” implies that the divine voice must somehow be accessible in our daily experience, for we are creatures who live one day at a time. If God wants to communicate with us, it has to happen in the course of a 24-hour day, for we live in no other time. And how do we go about this kind of listening? Long tradition has provided a helpful tool, which we call the “examination of consciousness” today. “Rummaging for God” is an expression that suggests going through a drawer full of stuff, feeling around, looking for something that you are sure must be in there somewhere. I think that image catches some of the feel of what is classically known in church language as the prayer of “examen.”

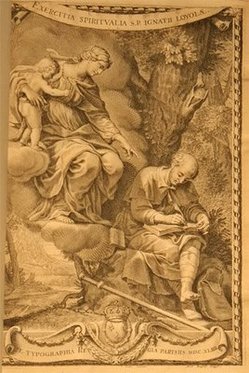

The examen, or examination, of conscience is an ancient practice in the church. In fact, even before Christianity, the Pythagoreans and the Stoics promoted a version of the practice. It is what most of us Catholics were taught to do to prepare for confession. In that form, the examen was a matter of examining one’s life in terms of the Ten Commandments to see how daily behavior stacked up against those divine criteria. St. Ignatius includes it as one of the exercises in his manual The Spiritual Exercises.

It is still a salutary thing to do but wears thin as a lifelong, daily practice. It is hard to motivate yourself to keep searching your experience for how you sinned. In recent decades, spiritual writers have worked with the implication that conscience in Romance languages like French (conscience) and Spanish (conciencia) means more than our English word conscience, in the sense of moral awareness and judgment; it also means “consciousness.”

Now prayer that deals with the full contents of your consciousness lets you cast your net much more broadly than prayer that limits itself to the contents of conscience, or moral awareness. A number of people-most famously, George Aschenbrenner, SJ, in an article in Review for Religious (1971)-have developed this idea in profoundly practical ways. Recently, the Institute of Jesuit Sources in St. Louis published a fascinating reflection by Joseph Tetlow, SJ, called The Most Postmodern Prayer: American Jesuit Identity and the Examen of Conscience, 1920-1990.

What I am proposing here is a way of doing the examen that works for me. It puts a special emphasis on feelings, for reasons that I hope will become apparent. First, I describe the format. Second, I invite you to spend a few minutes actually doing it. Third, I describe some of the consequences that I have discovered to flow from this kind of prayer.

A Method: Five Steps

1. Pray for light. Since we are not simply daydreaming or reminiscing but rather looking for some sense of how the Spirit of God is leading us, it only makes sense to pray for some illumination. The goal is not simply memory but graced understanding. That’s a gift from God devoutly to be begged. “Lord, help me understand this blooming, buzzing confusion.”

2. Review the day in thanksgiving. Note how different this is from looking immediately for your sins. Nobody likes to poke around in the memory bank to uncover smallness, weakness, lack of generosity. But everybody likes beautiful gifts, and that is precisely what the past 24 hours contain-gifts of existence, work, relationships, food, challenges. Gratitude is the foundation of our whole relationship with God. So use whatever cues help you to walk through the day from the moment of awakening-even the dreams you recall upon awakening. Walk through the past 24 hours, from hour to hour, from place to place, task to task, person to person, thanking the Lord for every gift you encounter.

3. Review the feelings that surface in the replay of the day. Our feelings, positive and negative, the painful and the pleasing, are clear signals of where the action was during the day. Simply pay attention to any and all of those feelings as they surface, the whole range: delight, boredom, fear, anticipation, resentment, anger, peace, contentment, impatience, desire, hope, regret, shame, uncertainty, compassion, disgust, gratitude, pride, rage, doubt, confidence, admiration, shyness-whatever was there. Some of us may be hesitant to focus on feelings in this over-psychologized age, but I believe that these feelings are the liveliest index to what is happening in our lives. This leads us to the fourth moment:

4. Choose one of those feelings (positive or negative) and pray from it. That is, choose the remembered feeling that most caught your attention. The feeling is a sign that something important was going on. Now simply express spontaneously the prayer that surfaces as you attend to the source of the feeling-praise, petition, contrition, cry for help or healing, whatever.

5. Look toward tomorrow. Using your appointment calendar if that helps, face your immediate future. What feelings surface as you look at the tasks, meetings, and appointments that face you? Fear? Delighted anticipation? Self-doubt? Temptation to procrastinate? Zestful planning? Regret? Weakness? Whatever it is, turn it into prayer-for help, for healing, whatever comes spontaneously. To round off the examen, say the Lord’s Prayer.*A mnemonic for recalling the five points: LT3F (light, thanks, feelings, focus, future).

Do It

Take a few minutes to pray through the past 24 hours, and toward the next 24 hours, with that five-point format.

Consequences

Here are some of the consequences flowing from this kind of prayer:

1. There is always something to pray about. For a person who does this kind of prayer at least once a day, there is never the question: What should I talk to God about? Until you die, you always have a past 24 hours, and you always have some feelings about what’s next.

2. The gratitude moment is worthwhile in itself. “Dedicate yourselves to gratitude,” Paul tells the Colossians. Even if we drift off into slumber after reviewing the gifts of the day, we have praised the Lord.

3. We learn to face the Lord where we are, as we are. There is no other way to be present to God, of course, but we often fool ourselves into thinking that we have to “put on our best face” before we address our God.

4. We learn to respect our feelings. Feelings count. They are morally neutral until we make some choice about acting upon or dealing with them. But if we don’t attend to them, we miss what they have to tell us about the quality of our lives.

5. Praying from feelings, we are liberated from them. An unattended emotion can dominate and manipulate us. Attending to and praying from and about the persons and situations that give rise to the emotions helps us to cease being unwitting slaves of our emotions.

6. We actually find something to bring to confession. That is, we stumble across our sins without making them the primary focus.

7. We can experience an inner healing. People have found that praying about (as opposed to fretting about or denying) feelings leads to a healing of mental life. We probably get a head start on our dreamwork when we do this.

8. This kind of prayer helps us get over our Deism. Deism is belief in a sort of “clock-maker” God, a God who does indeed exist but does not have much, if anything, to do with his people’s ongoing life. The God we have come to know through our Jewish and Christian experience is more present than we usually think.

9. Praying this way is an antidote to the spiritual disease of Pelagianism. Pelagianism was the heresy that approached life with God as a do-it-yourself project (“If at first you don’t succeed…”), whereas a true theology of grace and freedom sees life as response to God’s love (“If today you hear God’s voice…”).

A final thought. How can anyone dare to say that paying attention to felt experience is a listening to the voice of God? On the face of it, it does sound like a dangerous presumption. But, notice, I am not equating memory with the voice of God. I am saying that, if we are to listen for the God who creates and sustains us, we need to take seriously and prayerfully the meeting between the creatures we are and all else that God holds lovingly in existence. That “interface” is the felt experience of my day. It deserves prayerful attention. It is a big part of how we know and respond to God.

Father Dennis Hamm, SJ, a Scripture scholar, teaches in the department of theology at Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska. Reprinted from America, May 14, 1994. www.americamagazine.org.