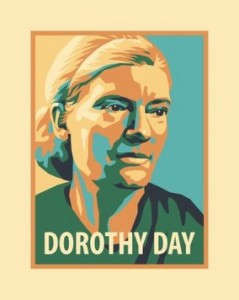

There are some among the Christian faithful who would prefer not to spend resources, personal and financial, on the sainthood investigation of the Servant of God Dorothy Day. As we know the US bishops have recently given their approval for the process to move forward. The for Day’s cause for canonization is being promoted by the Archdiocese of New York; Cardinal Timothy Dolan is a very strong supporter, as is Cardinal Francis George among others.

There are some among the Christian faithful who would prefer not to spend resources, personal and financial, on the sainthood investigation of the Servant of God Dorothy Day. As we know the US bishops have recently given their approval for the process to move forward. The for Day’s cause for canonization is being promoted by the Archdiocese of New York; Cardinal Timothy Dolan is a very strong supporter, as is Cardinal Francis George among others.I bear a burden of responsibility for publicizing that line, which I quoted in the introduction to an anthology of her writings almost thirty years ago. Where did it come from? I can’t honestly say. I do remember one time sitting at the kitchen table with her at St. Joseph’s house, looking at an issue of Time magazine in which she was included in a list of “living saints.” “When they call you a saint,” she said, “it means basically that you are not to be taken seriously.”

Whatever the provenance of her famous “quote”–the important question is: What did she mean?

Dorothy’s own relationship with saints was anything but cynical. Both her daily speech and her writings were filled with references to St. Paul, St. Augustine, St. Francis of Assisi, and St. Teresa of Avila. She treasured their stories. For Dorothy these were not idealized super-humans, but her constant companions and daily guides in the imitation of Christ. She relished the human details of their struggles to be faithful, realizing full well that in their own time they were often regarded as eccentrics or dangerous troublemakers.

But she didn’t just study their life and writings. She also firmly believed in their role as heavenly patrons. Whenever funds or provisions ran low she would “petition” St. Joseph. She would pray to St. Therese for patience and understanding. She would pray to St. Francis to increase her spirit of poverty. For many years, the Catholic Worker was largely illustrated by woodcuts by Ade Bethune depicting the saints in everyday dress, performing the works of mercy. She devoted many years of her life writing a life of St. Therese of Lisieux. I have no doubt she would have delighted in the news that St. Therese was named a Doctor of the Church. It is unthinkable that she would have responded by saying, “That means basically that Therese is not to be taken seriously!”

Furthermore, long before Vatican II took up the theme of the universal call to holiness, Dorothy Day taught that “we are all called to be saints.” As she noted, “We might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name. We might also get used to recognizing the fact that there is some of the saint in all of us. Inasmuch as we are growing, putting off the old man and putting on Christ, there is some of the saint, the holy, the divine right there.” In other words, Dorothy Day regarded sanctity as the ordinary vocation of every Christian–not just the goal of a chosen few.

What Dorothy certainly opposed–and what saint wouldn’t?–was being put on a pedestal, fitted to some pre-fab conception of holiness that would strip her of her humanity and, at the same time, dismiss the radical challenge of the gospel. “Dorothy Day could do such things (live in poverty, feed the hungry, go to jail for the cause of peace). She’s a saint.” For those who said this sort of thing, the implication was that such actions–which would be out of reach for ordinary folk–must have come easily for her. She had no patience for that kind of cop-out.